On Mette Edvardsen’s poetry and its penchant to imagine a clandestine side to things

I’ll begin by way of a harsh preamble, a critical diagnosis. What has happened, in Europe today, to artists’ imaginary? Are the authority of philosophy and critical theory in matters of art crushing artists’ conceptual or poetic imagination, despite their developed linguistic sensibilities and practices of self-reflection? My provocative claim is that instrumental reason has privileged the efficacy of images above all else, that the words and procedures favored by art institutions respond to a growing expectation that they manage the audience’s experience.

To imagine is to absent oneself;

it is a leap toward a new life

– Gaston Bachelard

Instrumentality is manifest in the kind of writing artists daily practice, a genre of persuasive expression: presenting one’s own work as accessible and credible, making it transparent and accountable, giving an advance preview, giving evidence of what will become a performance, a video, an installation. The manner of speaking in applications or post-hoc reports for subsidy bleeds into program notes in which artists’ intentions dovetail with the expectations of the audience. The audience is supposed to arrive knowing what it is going to see. It is in the economy of phrasing and in the performative promise of the experience described in just a few lines that the idiom of presenting art for the public is standardized. Paradoxically, this undermines the initial function of such presentations, which is that of choosing the words that individuate a specific work of art. The teasers I have in mind rarely convey anything distinctive about the work in question. However, they confirm a widespread conviction that power is about making things easy and that communication should reduce complexity and facilitate personal identification.

If this is the order of the day, how are we, artists, critics, and art theorists, to counteract the reduction of language by instrumental reason? This observation stands, by way of synecdoche, for a grimmer verdict. Namely, artists have little time left over, after performing the duties of being an artist, to engage in thinking about their art. All time is invested in practice, on the activities that administrate or reproduce a work, present or circulate or maintain it, but not on those that produce it. Poetics as the art of making, forming and composing, is out of purview. Working on poetics requires time, in the sense of duration and empty time, dead time, boredom, digression, distraction. Poetics entails the ability to imagine a future and to entertain the curious question, “What is the art I would like to see?” Such concern is counterintuitive to an imagination confined to the project you are intending next. The pressure that social and political crises exert on artists, who expect themselves, or are expected, to provide models or solutions, leaves even less space to imagine and project the art that one dreams of seeing in a future without knowing how to make it, without knowing whether it would be feasible at all. The problem is temporal: imagination is endowed in the future. “No future” is the bitter message of neoliberal reforms, and presentism is its social mood, an experience of time in which only the present is “real.”

The wager, in this line of thought, is to think out of deficiency, from the lack that structures the present horizon of making art. Could criticism prefigure or anticipate an early stage of something yet to emerge? Moving beyond the negative diagnosis of the current conjuncture, I would like to unravel elements of performance poetics in which imagination gains ground. This will amount to elaborating a few theses about imagination as it operates in the dramaturgy of performances from creation to reception. Far from a fully-fledged concept rooted in one school of thought, I will work out the features that associate diverse theoretical outlooks with an analysis of two works by the Norwegian choreographer Mette Edvardsen, No Title (2015) and Oslo (2017). Read them as propositions toward a notion of imagination.

We To Be, Mette Edvardsen

Imagination is the ability to think of something not presently perceived

In the genealogy of the philosophical concept, imagination was dependent on perception. To imagine meant to recall, or rearrange sense data, as in re-seeing or re-picturing something in the mind that was previously perceived. For empiricists and rationalists alike, it was analogous to, if not just an inferior kind of perceiving, imagining as “decaying sense” (Hobbes), or a “peculiar effort of mind” (Descartes) in which one tries to construct an image with “mind’s eye” based on perception or understanding. Although it was already with Aristotle considered different from either perceiving (aisthesis) or discursive thinking (noesis), imagination for the Pre-Moderns retained a confusing intermediate position between sensibility and the understanding, which was resolved for our modern purposes–as is often the case–in Kant.

Imagination can be thought in two ways, empirical or productive, Kant adjudicates. Empirical imagination gives rise to memory and anticipation by which we recollect or predict the presence of things absent. Productive or poetic imagination produces original representations, that is to say, ideas that have no experiential content nor are they derived from experience. Moreover, ideas produced by imagination provide conditions of experience. They aren’t willful or accidental such as products of fancy but ordered. What makes this kind of imagination productive or original is that it doesn’t apply laws of the understanding (as in recognition whereby intuitions are synthesized into concepts). Productive or poetic imagination simultaneously invents and applies laws in reflective judgment. (Kant)

Let us rephrase our initial proposition: imagination is thinking of something that is not what you are seeing. It is not just that you are thinking of something absent or unperceived. There is something present, there is something you are perceiving, and you are nonetheless able to relate to this something in such a way that it does not saturate you, does not prevent you from thinking something else as well or perhaps instead. As we are talking about performance, the elusiveness of presence and the condition of here-and-now, the exclusivity, and preciousness of the instant condemned to passing and fading in memory, are bracketed. A way to relieve theater from the self-reproach of representation comes as a shift in the theater’s quest from the experience of the impossible ‘real’ to the possible ‘imagined,’ independent of presently experienced.

In No Title (2015), the middle piece of the trilogy (together with Black and We To Be) by Mette Edvardsen, the performer is alone on an empty stage. Edvardsen herself is enunciating a series of speech acts. Their structure seems invariant: while the subject changes, the predicate remains the same. Something is gone:

the beginning–is gone

the space is empty–and gone

the prompter has turned off his reading lamp–

and gone

a room, not even a room

walls, other walls

a door, opening and closing–gone

the ceiling–gone

lamps and speakers, hanging–

shadows moving in silence–gone

Every Now And Then, Heiko Gölzer

From naming things that the situation of a theater performance is made of, and the audience can be made aware of, the utterances begin to ramify toward outer circles. They encompass abstract notions (“forms and planes,” “surfaces and shapes,” “things and beings–twice as invisible”), words from previous statements (“the distinction between thinking and doing is gone,” “distinction is gone,” “between is gone”), but also, taken by surprise, a theater play direction elaborating a scene, which also “is gone.” It is hard to determine the law by which the subjects are selected. While at times, a taxonomy of world problems could be discerned (“ignorance,” “acceleration,” “sea level,” “overpopulation,” “poverty, precarity inequality” etc.), a few notable references pop out in their blunt contingency (“Khrushchev’s shoe,” “Schrödinger’s cat,” “ ‘Now is the winter of our discontent…’”). The rhythm is one of invoking things only in order to erase them into the past. It flows like a film tape burning by words at their pace of utterance: steady and relentless. At the outset it is interrupted by a sort of refrain that points to the presence of the figure on the stage, the speaking performer, who says:

something’s gone

me–not gone

me–not sleeping, not done, not gone

and another time:

dog–gone

me–not dog

me–not dead, not bone, not not

and lastly:

all–gone

me–not all

me–not god, not all, but gone

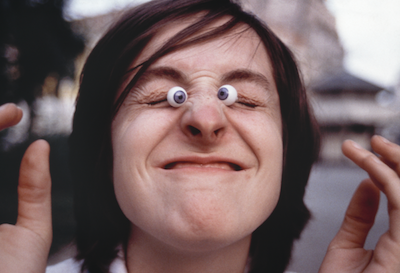

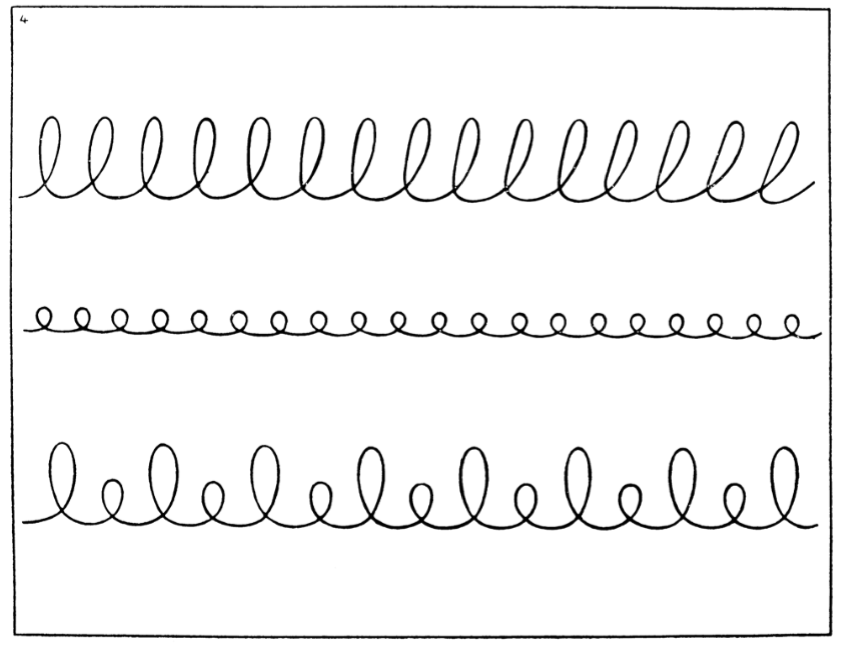

Twice has the performer crossed herself out: first, by closing her eyes (and keeping them closed for the length of all utterances) and second, by placing artificial eyeballs in her eyes (which keep her still blind although they give her the theatrical guise of looking like a doll with wide open unblinking eyes). Iterating negation becomes a wordplay of obstinacy and exhaustive variation when the predicate “is gone” is replaced by the monosyllabic “not”:

not alone

not not alone

not alone alone

not doing doing

not not doing doing

not not doing doing doing

not not doing not doing doing

doing not not doing doing doing

doing doing not not doing doing doing doing

doing not not doing doing not doing doing doing

not not not doing doing not not doing doing

not not not not doing not doing doing

not not not not doing not not doing doing doing

(…)

It is important to note that the performer tries to maintain the logic of multiple negations in the stress and tone of her speech, so the seemingly visual organization of the poem sounds reasonable and plausible for our ears. Logical sense is prominent in a series of disjunctions that assemble contrasting terms and near-opposite differences:

not up–not down

not standing–not sitting

not a dog–not a table

not coming–not leaving

not seeing–not looking

not same–not different

not no–not yes

not warm–not cold

not finding–not searching

(…)

The long series of opposites produces equivocacy through annihilation: if not this, and not not-this, then, inversely, both this and not-this is possible. Such constellation is against the law of excluded middle (everything must either be or not be). When the law of excluded middle applies–“if not one, then the other”–it is impossible to negate both. If both are negated, one is forced into “the middle” that is indeterminate in logic.

Every Now And Then, Heiko Gölzer

Time stands still. There is no reason for hurry as there is no progression. Admittedly, as the performance persists to devour the words of a world or the world of the words that it mounts, imagination resembles a journey that must come to an end. Exhausting the possibility of language to count and discount items has a liberating effect as if everything must go and it is no cheap sale:

everything that is not written down is gone

everything that is written down is gone

time is gone

the edges are gone

there is only inside, the outside is gone

illusion is gone

there is only outside, the outside is gone

darkness–gone

Imagination imposes language as a pattern onto the world

No Title is made of imagination without images. Instead of pictures evoking memories of the order of vécu (lived experience), which are said to be all different in every spectator, the spectator is presented the generic language of dogs, tables, something and nothing, simple clauses. She is not asked to fill up a color book with her own colors. So why should there be a relationship between genericness and imagination? It certainly is not because the ‘generic’ is easier to share than the singular. The opposite is the case, anyway according to common wisdom, which holds that people are more able to create a mental image if presented with a vivid and lush account. But, as we said, No Title does not give orders to its audience to form images. There is something powerful about the indifference of the generic, and the economy of bare contours rather than colorful and rich images. Resisting mystery, plenitude or intrigue, and offering substitution and exchangeability of thin images and disjunctions, it is the language that extends its power of movement aside from experience. In L’Air et les songes: Essai sur l’imagination du mouvement (1943), Bachelard notes:

How unjust is the criticism that sees nothing in language but an ossification of internal experience! Just the contrary: language is always somewhat ahead of our thoughts, somewhat more seething than our love. It is the beautiful function of human rashness, the dynamic boast of the will; it is what exaggerates power.

-Gaston Bachelard

Imagination is like feigning, pretending to know. Feigning takes place in the gap between ignorance and action

Recently, dancers have shown considerable interest in the so-called somatic reality of the body. A myriad of body practices has surfaced in Europe, each claiming to have discovered truer and more insightful access into viscera. Most of the times, this knowledge is framed as personal, contingent upon the idiosyncratic techniques of the practitioners. On a more rational view, some dance practitioners admit that it is a matter of imagination. We would regard this kind of imagination as feigning. In pre-Kantian philosophy, imagination is opposed to reason. For Descartes, imagination is worse than useless. In so far as it is an affection of the body, imagination is more of a hindrance than a help in metaphysical speculations. For Spinoza, imagination is an inadequate kind of knowledge, also called feigning, or pretending to know. In a somewhat unfaithful reading of Spinoza, Christopher Norris suggests that fictions that are products of imagination ought to be considered as expressions of a positive mental capacity: the capacity to feign (Norris). We feign not that which we know to be true or that which we know to be untrue, but that of which we are ignorant. Feigning is inversely proportional to understanding, but as long as we treat it as an aid to, rather than a substitute of, understanding, it is a point of access to truth.

Why do we agree to feign? Because we are ready to imagine things that we know are not the case, not actual, or not in the realm of knowable. In L’eau Et Les Rêves (1942), Gaston Bachelard writes that: “imagination is not the faculty of forming images of reality, it is the faculty of forming images which go beyond reality, which turn reality into song. It is a superhuman quality.” We are ready to feign sensations out of curiosity that takes us beyond knowledge. And this might entail an illegitimate use of reason that pokes its nose into a furtive reality. André Gide writes in his autobiography, Si Le Grain Ne Meurt (1926) of a vague, ill-defined belief that “something else exists alongside the acknowledged aboveboard reality of everyday life.” This “desire to give life more thickness,” Gide suggests, elicits “a sort of propensity to imagine a clandestine side to things.” (Gide)

Imagination is environing

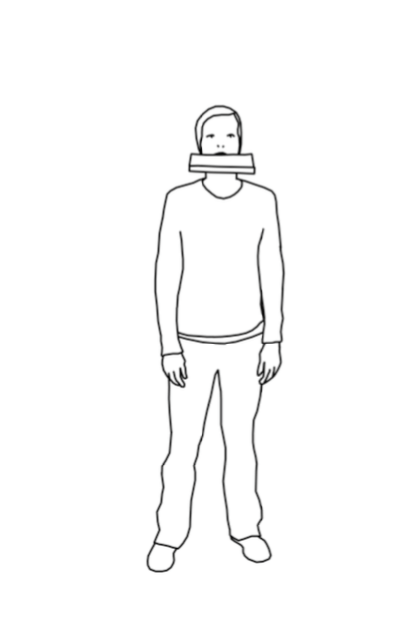

To visualize what remains unseen is to come closer to conception and conceivability. In thinking that I am having a sensation of something that I don’t presently perceive, I include my seeing in what I visualize. It is not about seeing myself in the image or becoming part of it, but about embedding my own gaze in the image, listening within the image, as I see and hear it. This happens because of a certain thickness of environment that threatens to grow into a whole and suggests a world that arises beyond the positivity of what is present. The image doesn’t need to be dense in order to envelop and set up a world around its audience. In Edvardsen’s performances, the image is rather thin and occasionally bursts out into more intricate accounts that nonetheless retain the same structure of a proposition, always one among many possibilities. In oslo (2017), the main proposition “A man walks into a room” runs through (what seems like) a thousand situations. At first, these are oscillations among resembling terms warming us up for uncertainty, as if the sense itself stutters:

A man walks into a room and the room is empty.

A man walks into a room and it’s the beginning of a story.

A man walks into a room.

A man walks into room with no furniture.

A man walks into a room full of people.

A woman walks into a room.

A woman or a man walks into a room.

A man is in a room.

A room has a door.

A man or a dog walks into a room.

A man follows a dog into a room.

A man walks a dog in a room.

A man walks around in a room.

(…)

Later on, as we expect yet another iteration on the proposition “A man walks into a room,” other unexpected images with reflected comments are smuggled in, like glitches straying from the main course:

A man walks into a room and says one thing and does another.

Another woman walks into a room.

A man walks into a room offering something completely different and persuading us that we are better off that way.

A man walks into a room and does something new.

An old dog walks into a room.

A lazy dog walks into a room and a quick brown fox jumps over it.

A man walks in a straight line into a room.

A man walks into a room carrying a box.

A man walks into a room with a hat, a cat, a suitcase, flowers, with a girl, with a gun, on a bike, on a camel, on a stage.

A man’s words are not one with the world they describe.

(…)

Imagination opens the realm of possibility as simply as it is to say that to imagine something is to think of it as possible, and not necessarily, being so.

Every Now And Then, Heiko Gölzer

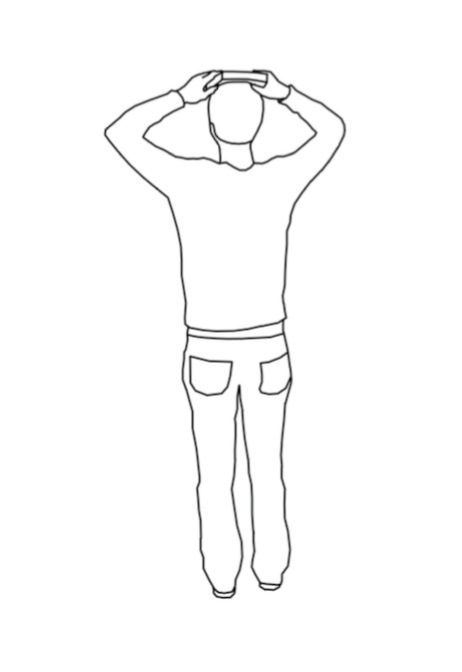

The deceitful sense that anything can be imagined after so many variant propositions is the effect of creating a world, a universe of propositions. To compare it with writing poetry would not be odd, as at a certain moment the spoken words leap onto a LED beam emitting a written text. The performer’s voice stops, but the listening is interiorized through the voice of each spectator who reads it to herself. “A universe of sentences arranges itself in an organization of images that often follow different laws, but that always observe the great laws of the imaginary” (Bachelard). But this won’t be enough, to have the propositions pound inside me. The LED beam doubles and the text begins to play with contrary sense and a literal gesture of enjambment. Ultimately, a choir of singers, sitting among other audience members, takes over the poem and chants it:

A man walks and walks and walks.

A man walks out of a room and something happens.

A man walks out of a room and nothing happens to the man, or very little.

A man walks down the stairs and out of the building.

A man walks up the street, around the corner and into people.

A man walks on a street.

A man looks up to the window of his room.

A man looks at other windows of other rooms.

A man looks at people on the street.

A man knows his way.

A man walks away into the city (an endless city).

A man walks down a street and the birds are singing (endlessly).

A man thinks he cannot be walking the right way.

(…)

Every Now And Then, Heiko Gölzer

Edvardsen’s poem is now clothed in a song, composed by Matteo Fargion. Combining speaking, singing and reading yields a contrapuntal finale – a richness that entails the exercise of various modes of reception in parallel. We are reading, listening to a melody, and discerning the sung and the spoken text. The performance has environed us, enveloped us with its words holding our ears and eyes in abundance.

Imagination begins with listening…

The two performances I have discussed here demand that their audience listen. Listening in its emphatic sense suggests obedience (the one who listens obeys). However, I experience the opposite in the context of these works: freedom from participation, from speaking or doing any other kind of action in order to verify my activity as a spectator. The phenomenology of this freedom is in my ear that acts as a funnel collects and swallows every word because this is almost all there is. While the sense of vision is connoted with clarity, with lucidity, with the total grasp and control of space, the activity of listening entails temporalization and an attitude of reception. To be able to imagine, one must initially trust the words that draw them into a world, and accept that this world might turn out obscure or mute or colorless, and most of all indifferent to my thoughts about it. This mode of reception is similar to the imaginary engendered by reading or listening to someone reading you a book or a poem. The locus of listening is the interspace of the body and text; listening contracts neither at the impression of the voice nor at the expression of the words (Barthes). There is an unconscious texture that associates the body-as-site and the words spoken and read, which comes through the voice and the rhythm of written or spoken sentences.

While trying to distinguish elements of poetic imagination in performance poetics, I have reflected them as a dramaturge, someone standing midway between the artist and the recipient of the work. Now some of my initial concerns return… If artists seek to unravel an imaginary, does this imaginary find a sympathetic ear? Far from suggesting that there is no excited reception evolving around these performances, I am wondering about how imagination transforms the theatrical apparatus of spectatorship. If a performance refuses to play the game of hide-and-show (Lyotard, Knap & Benamon), of persuasion of presence and the experience of the real, because it prefers to present itself as a poem, in words that may or may not carve out an interspace for the spectators’ own capacity to imagine, then the spectators are no longer called in as witnesses to a stage event. They are there, like the performers, entering a space in which imagination is alone, words and images take flight and are lost.

To leave the audience alone, trusting it is capable of participating in an imaginary, seems so difficult, at odds with the current curatorial care. To leave the artists alone, trusting that their art that they are developing, is worthy of our attention, without that it first prove its worth, would be needed. Let’s find the means, give them the means, the audience, and the artists, to be left alone to find the thoughts, images, and sensations we didn’t have before.

This article was originally published in Etcetera on September 14, 2018, and has published with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Bojana Cvejić.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.