Until the beginning of February, the New York MoMA is mounting an exhibition on Judson Dance Theater. In the sixties, this legendary collective, which used the Judson Memorial Church in Greenwich Village as its home base, paved the way for a postmodern dance and performance which steered clear of the formalism of modern dance. The influence of Judson Dance Theater on the development of contemporary dance in the last decades of the twentieth century is undeniable. But what can the movement mean to millennials who are trying to find their place in the world of dance today?

This review of the Museum of Modern Art’s ongoing exhibition of Judson Church Dance Theater rests on an impossibility, and this is not solely due to the sheer challenge that its object presents to the acts of capture in the forms of either retrospective or review. My observations are limited to the exhibition of the photographs and other documents, and entirely miss the parallel programming that includes a generous selection of performances and video screenings of the major Judson artists. The exhibition rests on curators Ana Janevski and Thomas J. Lax’ extensive research on primary sources, including photographs, performance scores, posters, evening programs, and contemporary reviews.

I visited the exhibit during the surprisingly calm afternoon hours of Columbus Day. At the Marron Atrium, the entrance hall to the museum’s galleries, I was greeted by a large video projection of David Gordon’s CHAIR – alternatives 1 through 5, a grainy 1979 film in color by Merrill Brockway. Inside a studio with hardwood floor, Gordon and Valda Setterfield stand next to two chairs and calmly go about to explore what they can do besides sitting on them. It plays out like a game, serious enough for them, curious enough for the onlookers. In perfect synch, they fluently shift from seated to lying, from falling on all fours to lifting the chairs above their heads. The stakes are raised a bit higher as their movements begin to syncopate while they introduce balances and off-balances standing on top of the chairs, and while their legs and the handles are tangled and untangled. There is a little bit of smiling perhaps, and maybe the gymnastic outfit is deliberately ridiculous, but their movement manner is as neutral as possible, devoid of any distinct emotion or show-off acrobatics. If the task is to make a chair, that iconic and prosaic object, strange and full of bodily possibilities, then Gordon and Setterfield are completely dedicated to it.

Gordon’s piece sums up some of the major tenets of Judson’s inventiveness. Apparently, this was the first day of Gordon’s program at the Atrium, following the two-week run of Deborah Hay’s performance videos from the late 1960s as well as a live performance of her Ten (1968) over three afternoons. As part of the moving-image selection, performance videos from each Judson choreographer are looped over a period of a few days or weeks, curated by video artist and film director Charles Atlas. A video essay by Atlas is mixed in the loop; edited in quickly changing sequences between various dances before one can guess the context or identify who is who, the video culminates in a collage of six choreographers whose works are featured in the Atrium within the performance and moving image program: Hay, Gordon, Yvonne Rainer, Lucinda Childs, Steve Paxton, and Trisha Brown. Memorable images from Group I, Matter, Trio A, Katema, Goldberg Variations, and Water Motor, respectively, divide the screen with their heterogenous paces and energies, yet they share a sense of actively thinking and researching. One of the leading figures of experimental videography for postmodern dance and performance, Atlas primes the visitors for a lively and playful experience, an affect that can be easily forgotten when one deals with “the archive,” especially one that is increasingly self-referential and highly paradigmatic in the contextualization of “contemporary dance.”

Next to the Atrium, the exhibition is spread over four galleries connected with each other. The smallest gallery at the one end shows an installation of Gene Friedman’s 1964 film 3 Dances, another collage of visitors strolling through MoMA’s Sculpture Garden, Judith Dunn working alone in a studio, and several Judson choreographers socially dancing at the church’s basement gym. The largest gallery at the other end brings together moving and still images from the Judson dance concerts between 1962-1964, as well as from other performances that took place in New York, New Jersey, Connecticut, and Sweden until 1966. In between, one gallery focuses on the church itself as an organization within the Washington Square complex and the downtown art scene of the period, showcasing MoMA’s acquisition of Simone Forti’s Dance Constructions (1960-61). The other gallery, entitled “Workshops,” goes back in time a bit (and expands to the West Coast, to Anna and Lawrence Halprin’s Dance Deck) to reveal the artistic influences that made Judson possible: Merce Cunningham and John Cage’s experiments with scoring and chance operations pass down through Robert and Judith Dunn’s composition workshops, which meet an intriguing counterpoint with James Waring’s playful theatricality in his workshops at The Living Theatre, and gain a liberating vibrancy through Halprin’s improvisation classes.

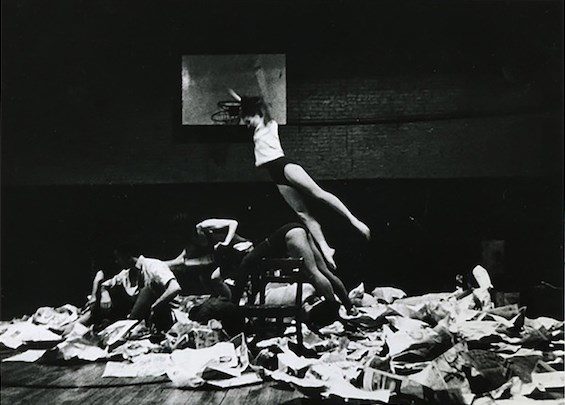

Ten, Deborah Hay (1968), performance in Judson Dance Theater: The Work Is Never Done, The Museum of Modern Art © 2018 The Museum of Modern Art & Paula Court

Inadvertently, I visited the exhibition in reverse order, starting with the main Judson gallery, “Sanctuary,” and moving on to the contextualizing galleries. I suspect that this desire to start with the actual images stems from a deep hunger to see, to look at the bodies and their motions and have the joy of filling in the inevitable gaps on my own. Unless one was alive to see it as it was unfolding or fortunate to catch a reconstruction event, one’s entry to the Judson phenomena is almost always through the discourse around it. Within the six decades following its emergence, a web of commentaries and conceptualizations were spun around Judson dance; it became a frame of reference in the historiography of contemporary dance, and perhaps contrary to its nature, calcified into an elusive but somehow functional aesthetic placeholder. The work of interpretation, the analyses of what Judson achieved and what it means for the “future generations” somehow always overshadowed it as a creative and communal process by living, moving, halting, confused, and confusing bodies.

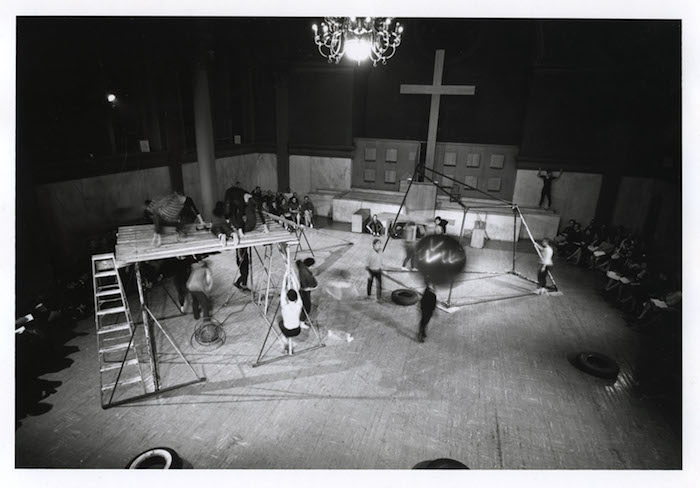

Slant Board, Simone Forti (1961), performance in Judson Dance Theater: The Work Is Never Done, The Museum of Modern Art © 2018 The Museum of Modern Art & Paula Court

What animates the exhibition is this desire to recollect that process and the multiplicity of ideas and methods it generated. I was immediately captured by two digital slideshows, each placed next to the facsimile program notes that list the showcased performances of two concert evenings. The earlier one, Concert Dance #3, took place in January 1963 at the basement gym of the church. Thanks to the numerous photos by Newsweek reporter and Judson enthusiast Al Giese, we see some rare images such as Trisha Brown in a mock musical theatre pose with only one shoe dangling from her foot, Paxton and Rainer, almost naked, in the beginning of a rond de jambe, or Fred Herko striking an arabesque in street clothes. Other slides show William David and Barbara Lloyd frozen in a lyric embrace, yet the transistor radios attached to their leotards give a hint of the estrangement they were after. Carolee Schneemann’s famous Newspaper Event was the finale to this evening, with bodies running, jumping, lying entangled in sheets of newspapers. Betraying a transitional residue of modern dance in some of the pieces, the nonhierarchical presentation of these different forms and investigations in the span of a single evening testifies to the variety of interests under the group’s umbrella.

Judson Dance Theater: The Work Is Never Done, The Museum of Modern Art: installatiebeeld

© Eylül Fidan Akıncı

The other slideshow presents photographer Peter Moore’s record of Concert Dance #13 at the church’s main sanctuary, just ten months after the #3 and near the end of these showcase series. Some form of cohesion can be glimpsed between the individual pieces of this “collaborative event,” at the center of which stands an installation that consists of a trapezoid, a ladder, wooden ramps, scaffolds, tires, and ropes. Negotiating the differences among bodies, materials, and intentions, an image of two groups of people pulling a rope at both ends exemplifies how physical tasks and external obstacles direct bodily motions rather than inner emotional states. The designer, Charles Ross, is seen on site as he modifies his environment, which each choreographer interprets differently: as a movement score, material structure, or choreographic problem. Not long into the slides, the environment itself appears as the locus of connection between these various approaches, a concrete as well as conceptual platform by which the pragmatic movement principles that came to be associated with Judson emerges. This dynamic environment triggers a unique exuberance in bodies, caught in a chaotic blur in the pictures, under the veneer of simple and defined actions. The two slideshows of group concerts bring nuance to the (paradoxically authorial) interpretation of the Judson aesthetic as a minimalist and depersonalized system of tasks and deeply complicates the notion of objectivity as abstraction and detachment. Due to the gaps in the archiving of the concerts and due to the proliferation of performances by Judson choreographers outside these evenings, the curators opt for a thematic organization rather than a chronological one. This way, they highlight key elements discovered or developed in the choreographic investigations associated with Judson: improvisation, environments, processes, scores, group dynamics, ordinary gestures, props, camp, and intermedia.

The discursive element of the exhibition comes directly from the members of Judson themselves. Janevski and Lax conducted interviews with Rainer, Halprin, Alex Hay, Schneemann, Gordon, Setterfield, Paxton, Aileen Pasloff, and Forti. While I wanted more than the short segments of the artists’ commentary about how transformative it was to find a community with Judson, one sentence from Schneemann hit me strongly:

“We were all sharing this sense that the culture had to be changed and we could do it.”

In the main gallery, we also see excerpts of interviews from 1983 with Judson Church’s cultural programmer Al Carmines, Paxton, and Schneemann, in conjunction with the 1980-1982 “Judson Dance Theater Reconstructions” co-organized by Bennington College and the Danspace Project. This reads as the MoMA curators’ nod to the historicity behind their endeavor, acknowledging the reconstructive effort spearheaded by Wendy Perron and Tony Carruthers some thirty years ago to historicize and maintain Judson’s legacy. Also combining a live performance program by 14 Judson choreographers with an exhibition, an oral history project, and the publication of Sally Banes’ Democracy’s Body: Judson Dance Theatre, 1962-1964 (1983), Bennington and Danspace’s project seems to be a blueprint for the methodology of the MoMA exhibit.

David Vaughn, reviewing the reconstruction project for Dance Magazine’s September 1982 issue, comments:

“It is ironic, of course, given the fact that impermanence was a fundamental premise of the Judson aesthetic, that certain works have attained the status of classics, at least by reputation.” [1]

A significant part of that reputation was built by critic and author Jill Johnston’s regular reviews in Village Voice, whose influence the MoMA curators underline by using excerpts from her texts throughout the exhibition. Similarly, they include Diane Di Prima’s review of the first Judson concert as it appeared in the underground poetry zine Floating Bear. The last paragraph of the review is prophetic:

“At this distance, the evening retains its excitement, the high one feels being in on a beginning; these people working out of a tradition […] yet in each case doing something that was distinctly theirs, unborrowed, defined.” [2]

About the same concert, Johnston writes “[T]his was an important program in bringing together a number of young talents who stand apart from the past and who could make the present of modern dance more exciting than it’s been for twenty years (except for an individual here and there who always makes it regardless of the general inertia).” [3]

Both responded and contributed to the feeling that Judson was a history-changing emergence, an eventful generational turn, even as it was just beginning to unfold.

Janevski’s essay in the exhibition catalog acknowledges the inevitable question as to whether this exhibition would function as an antithetical reification of a decentralizing moment that was essentially a flight from aesthetic codifications of institutions [4]. Janevski and Lax’ curatorial choices in the exhibition design and their modesty in making the exhibition an occasion for the extensive performance program could overcome such reification. They opt for a compact display, which keeps the visitors yearning for more and willing to come back for the performances. Although the choreographers in the program presented their Judson-era works over several retrospectives, bringing these works to a broader, non-specialized public together with an instructive and dynamic archive carries out the significant task of fleshing out Judson for the collective memory.

THE MATTER, David Gordon, performance in Judson Dance Theater: The Work Is Never Done, The Museum of Modern Art © 2018 The Museum of Modern Art & Paula Court

THE MATTER, David Gordon, performance in Judson Dance Theater: The Work Is Never Done, The Museum of Modern Art © 2018 The Museum of Modern Art & Paula Court

That said, I can’t escape the feeling that Judson is an always-already celebrated presence. Although there are gaps in its historiography and its public reception, and although it situated itself in the margins of the cultural establishment, Judson was being reviewed, documented, archived, analyzed, and revived pretty regularly and with an appreciation of its originality since its emergence. The second revival effort after Bennington, Mikhail Baryshnikov’s Judson reunion project PASTForward, kicked off the new millennium, to be followed by further revisits in the dance world and in larger artistic conversations. Presenting an alternative approach to Banes’ influential historiography and analysis, Ramsay Burt’s Judson Dance Theater: Performative Traces (2006) examined Judson’s influence on contemporary European choreography alongside Baryshnikov’s revival tour. On the 50th anniversary in 2012, Danspace Project and Movement Research, both organizations dedicated to promoting and providing space for experimental choreography in New York City, each assembled significant forums among the Judson cohort and the new generation of artists, along with a series of reperformances. In a way, the MoMA exhibition builds on this intensified resurgence of Judson, while its brand-power carries the risk of giving the final word on it. And yet, if returning to Judson is a millennial affair (with a little curse, considering Schneemann’s words quoted above, of an impossible utopia for the artists who are millennials now, the same age range as the Judsonians were), perhaps it is all right to give the revived spirit some grand finale as this haunted decade comes to a close.

NOTES:

[1] David Vaughn, “Judson Dance Theater Reconstructions,” Dance Magazine 56 (September 1982), 48-9.

[2] Diane Di Prima, “A Concert of Dance – Judson Memorial Church, Friday, 6 July 1962,” Floating Bear 21 (August 1962).

[3] Jill Johnston, “Democracy – August 23, 1962,” in Marmelade Me, exp. ed. (Hanover and London: University Press of New England, 1998), 40.

[4] Ana Janevski, “Judson Dance Theater: The Work is Never Done—Sanctuary Always Needed,” in Judson Dance Theater: The Work is Never Done, eds. Ana Javeski and Thomas J. Lax (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2018), 29.

This article originally appeared in e-tcetera.be on January 7, 2019, and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Eylül Fidan Akıncı.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.