This is the third of a series of articles to discuss the Dialogue of Civilizations theater education program. The focus this time is to delineate its progression from an idea Vahdat Yeganeh formed while a young theater artist living in Iran, to become one of American Repertory Theater’s in house theater education programs. American Repertory Theater, a part of Harvard University, is a leading force in American theater, and highly regarded for presenting innovative theater in Cambridge, MA.

Yeganeh, born in Iran, created the Dialogue of Civilizations program inspired by former Iranian President Mohammad Khatami’s practical implementation of Iranian scholar Dariush Shayegan’s writings. Khatami introduced Dialogue Among Civilizations to the United Nations General Assembly in 1998.

The United Nations Year of Dialogue Among Civilizations was proclaimed in 2001. Tragically, its aims were overshadowed by the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks in the United States. Kofi Anan, the then Secretary General of the United Nations, remained steadfast about the importance of dialogue in his speech made in 2002:

The United Nations itself was created in the belief that dialogue can triumph over discord, that diversity is a universal virtue, and that the peoples of the world are far more united by their common fate than they are divided by their separate identities. This dialogue must take place every day among all nations – within and between civilizations, cultures and groups. But it must be based on genuinely shared values.

Heather Waters’ recent articles explore theater education’s potential to create new jobs at a time of profound global economic uncertainty due, in part, to forecasts of AI taking over many current jobs and concerns that refugee populations are increasing due to the adverse effects of climate change.

Heather Waters: In an article published by the United Nations in 2012, Mohammad Khatami, President of Iran at the time, wrote that Dialogue Among Civilizations is not a philosophy or a theory, but a paradigm: “a desirable model and example for relations among humans, societies and different groups… When the existing paradigm is one of war, domination and violence, the world needs to hear the voice of peace, dialogue and compromise.” Have you adopted a similar paradigm for Dialogue of Civilizations as a theater program? Or how is your vision of Dariush Shayegan’s writings, as theater, different from Khatami’s at the U.N.?

Vahdat Yeganeh: This is a profound question for me. I will start by saying that President Khatami introduced me to the concept of Dialogue of Civilizations. For people of my generation, Shayegan’s philosophy was not known in Iran because his books were banned and he lived in exile in France. At the age of 19, I was working in theater and journalism. This is when Khatami was making his speeches at the United Nations, and this is how I got introduced to Dialogue Among Civilizations.

HW: So Khatami was talking about the concept of Dialogue of Civilization while the President of Iran and Shayegan was banned at the time?

VY: Yes, one of the most phenomenal things Khatami did was invite Shayegan back to Iran–and not just Shayegan–but a lot of artists who had been banned since the 1979 revolution. They came back as movie directors. actors, writers, their books got published. Khatami opened up the cultural conversation in Iran based on his philosophy of Dialogue of Civilizations. In Iran, you have to get permission from the government to either publish your book or perform a concert.

HW: That is still going on, right?

VY: Yes, it is still going on. Khatami’s administration would give artists permission to perform but the extremists would cancel the shows. They would give permission for newspapers and the extremists would close those newspapers. I am glad you asked that question because there has been confusion about if Khatami was doing the censoring, but the President is not the most powerful person in Iran.

HW: That sounds similar to what is going on here now with banned books.

VY: Absolutely. It is starting here in America, which is very disturbing. Coming back to your question, how I adopted Dialogue of Civilizations to theater, I was born in 1979 at the time of the Islamic Revolution. I was two years old when the Iran-Iraqi war started, and it went on until I was ten years old. I was born and raised in a Baha’i family and the Islamic Republic did not recognize Baha’is. The Baha’i people could not go to university, could not work in government. The Islamic Republic killed a lot of people during and after the revolution, and a lot of Baha’i people got imprisoned or killed. Persecution of the Baha’is still exists today. When I got introduced to Dialogue of Civilizations, creating dialogue between different groups made a lot of sense to me based on my life at the time.

HW: A journalist and theater artist, you were only 21 when you fled Iran for Turkey on foot. How did your journey to Turkey, and your experience living there as a refugee, influence development of Dialogue of Civilizations?

VY: In the refugee camp we were not allowed to work. Friends from Iran would send me books. I was reading Shayegan and many theater books.

HW: How long did you live in Turkey?

VY: Almost two years. During the first year I was living with refugees from Syria, Iraq, and Iran in the city of Van’s U.N. office. Living with people with different political ideas and different religions, the concept of Dialogue of Civilizations was again making sense.

HW: Did you develop theater techniques in Turkey?

VY: I wouldn’t say techniques got developed in Turkey, more the philosophy. By the time I got to the United States, I came with the mind that I have to be constantly in dialogue–with new culture, new language, new custom, new history of the U.S. It was much later, in 2014, I started practicing it in theater at Boston Experiment Theatre.

HW: Why experimental theater? Was it experimental in part to bring in traditional Iranian theater? Or was it your interest in Grotowski and Artaud?

VY: The company was founded in 2008 with the mission of practicing the theater of Grotowski and Artaud. The concept of Dialogue of Civilizations was added to the company in 2014. In 2014 there was talk of war between Iran and the U.S. I started inviting actors and musicians from Iran to come to Boston to rehearse and perform with American actors and musicians. We started experimenting with fusing traditional Iranian theater and music with Western theater and music–from the Grotowski point of view.

As an artist I felt I had a responsibility to do something, especially being a person raised in war. I know what war does. My hope was if audience members come to see an Iranian play translated from Farsi to English, see Iranian actors working with American actors, and get to know each other more thorough talk-backs, maybe the next time they watch the news about Iran, they will remember these artists, that they live in Iran with their families. Maybe they will ask the question, do we really want to be in a war with these people? It is always easier for us to hate ones that we don’t know. Some people get confused that the Dialogue of Civilizations is to create peace among everyone, I don’t believe it is possible to create peace among every human being.

HW: I don’t think so either.

VY: It is not the nature of human beings, but it is possible to help one another to acknowledge others so we can live among one another with our own traditions, our own thoughts, politics, identities, our own religion, our own races–keep our identities and not be faced with the threat of a war: if you don’t become like me, I am going to kill you.

HW: I love how you put this–everyone gets to keep their own identities. I have this preoccupation, and I think being a white person allows me the luxury of this preoccupation, but I get frustrated how the red state, blue state divide in America prevents the lower and middle classes, and the upper too, from organizing collectively against income inequality, which, needless to say, is alarmingly high. Forming alliances by identity politics does make sense, progress is being made this way, but I wonder how can we all also get together to confront nationally, globally really, income equality, if it involves aligning with groups we don’t like, or despise even, their politics.

VY: Since the 2016 election we see both sides demonizing each other, it doesn’t matter if red or blue, they are demons. More than ever the United States needs to practice the concept of dialogue of civilizations. Once again, it is not that the values have to be the same. They just need to acknowledge each other’s values and after that learn to work with each other.

HW: This might be a good segue into your experience now working with American Repertory Theater. A.R.T. always hires such interesting theater artists to work for it. Being a much larger organization than Boston Experimental, and part of a major university, brings it closer to the U.N. idea—and with more bureaucracy to contend with. What has been your experience at A.R.T.?

VY: It has been almost two years since I’ve been working at A.R.T. I am very happy to tell you I get full support from management and producers to run and practice the program of Dialogue of Civilizations at A.R.T. The resources there, and opportunity and support, are amazing. We started collaborating with The Immigrant Learning Center in Malden, Massachusetts, the ILC, which is one of the biggest organizations to support immigrants and refugees arriving in the U.S. The ILC provides immigrants and refugees with English classes, helping them to find jobs, helping them with their paperwork regarding immigration status, any help they need. So we started collaborating with them.

I would say there are two main goals that we have been practicing these past two years. One is to bring A.R.T.’s theatrical resources to immigrants and refugees. We get people in our workshops from all over the world. They come from Syria, Iraq, Iran, China, Haiti, Brazil, Argentina, and Russia–many countries. We teach them theater techniques to help them learn and speak English, build confidence to speak in front of the public, and get engaged in conversation. Tickets to shows and classes are free. We provide them with shuttle buses to and from the theater to see the main stage shows. We encourage them to come to the theater so they know this art center exists for them in their neighborhood.

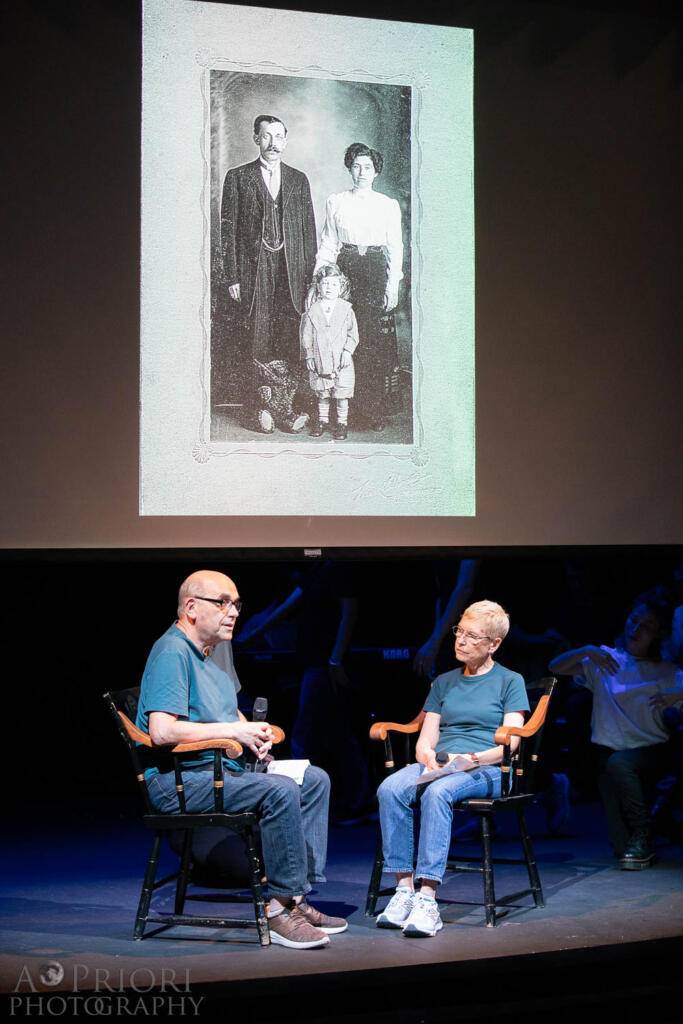

Cast of LOST/FOUND : Viktor Rabkin and Larisa Faddeyeva during the July 28th performance at Harvard University’s Agassiz Theatre in Cambridge. PHOTO CREDIT: A Priori Photography

Also, very important to me is to give refugee and immigrant communities the opportunity to share their stories and experiences. We use the concept devised drama that I have been practicing at Boston Experimental Theatre since 2008. We write the stories together, but we never write the script for them or tell them what to write. Instead, while we play theatrical games, we encourage them to share their feelings and thoughts. Obviously, they miss their home countries, their families, friends, food, and speaking to people in their own languages. It is important to mention that we never correct their grammar or accents. Broken English is part of our identity as immigrants.

A lot of them escaped from countries with dictators, and they are excited about the prospect of a new start. During the workshops, we discover that we share many of the same anxieties, fears, and sadness. No matter how long you live in a new country, many anxieties and fears never go away. I have been living here for 22 years, and I still have them, and I share this with my students. Very rarely do immigrants and refugees get to share their stories publicly with communities they live in. We have been able to support them like this at A.R.T. because the managers of A.R.T. create this great environment that we can practice in.

We create the show within ten weeks and then perform it for audiences at American Repertory Theater. While the shows have moments of struggle, there are also moments of celebration of being together. Recently a Syrian actress brought in Syrian music, which our musician adopted for the stage. She then taught two other women from the workshop, one from China and the other from Brazil, an Arabic dance. During the performance of it, they invited people from the audience to come to the stage to dance with them.

After the shows we have a reception. We meet the audiences in the lobby, have snacks from around the world, drinks, talk about the show, and share personal experiences the show brings to mind. The audiences are mostly American, but also people from other parts of the world attend. A man from France, for instance, shared with some cast members during the reception that he missed his home in much the same way they did.

HW: You explain the idea of theater as a shared moving experience really well here: how there is struggle but also celebration in the show, and the result is a positive feeling among both audience and performers.

VY: This is the definition of Artaud’s theater of cruelty for me – you have this cruel experience of hearing these sad stories of refugees and immigrants, yet the result is positive for both sides – the performers and the audience. Artaud and Grotowski wouldn’t call this type of theater work drama therapy. I am not very comfortable calling it drama therapy either, but sometimes I do use the term.

HW: Tell me about Little Amal coming to Harvard Square.

VY: I was very honored to be a part of that. Brisa Areli Muñoz was the project director to welcome Little Amal to Harvard University, and Donya and I were part of her team as associate creatives. Little Amal was visiting Boston on her first day in the United States.

HW: For our readers, Donya, your wife, is Donya Pooli Yeganeh, an actor, playwright, and director, who also emigrated here from Iran.

VY: During the month of August, A.R.T. held free workshops at libraries in anticipation of Little Amal, to introduce community members to her, and to invite them to become a part of the welcoming ceremonies for her. I was happy to see twenty-three people from the library workshops, and seven students from the Dialogue of Civilization workshops, were a part of the welcoming ceremonies. There were performances, reading poetry, movement, dances, to accompany Little Amal. Little Amal as a ten-year-old Syrian refugee walking around the world to find a home, find her mother, new friends, is an experience all refugees share. I admire the company that created Little Amal–the Handspring Puppet Company. I love their mission to help refugee children around the world get donations. Home for me has always been theater and being able to practice Dialogue of Civilizations at A.R.T. and be a part of welcoming Little Amal feels like being home for me.

HW: It sounds like a lovely event. Unfortunately, there are also public events where anger is directed at refugees. People who have trouble empathizing with refugees–maybe they can’t picture themselves being in such a perilous situation. Or it is too scary to try and imagine it. Or they see them as competition for jobs and resources, and immigrants too. Can you go into the significance of welcoming Little Amal and the theme of welcoming to the concept of Dialogue of Civilizations specifically?

VY: The Little Amal project is a symbolic and meaningful theater project to practice the concept of welcoming, but one would be wrong to think that after Little Amal leaves everyone will be very welcoming to refugees. This is my personal experience that I am discussing. From my personal experience, this practice is to create more conversation around the refugee crisis rather than solving the problem of it. And I think whether we are talking in theater, art, politics or newspapers, we don’t have enough of this type of conversation in the United States. We do have enough of blaming each other. Blaming others never works and nothing gets solved.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Heather Waters.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.