Why is this boy-kills-girl play different from all other boy-kills-girl plays? For starters, it might not be, but for me, Marie It’s Time, Julia Jarcho’s delightfully perverse riff on the 1834 Büchner play Woyzeck, is compelling enough to justify a foray into the potentially troubling depths of the human psyche.

The original Woyzeck tracks the title character, a proto-working class hero type, through the many indignities of surviving in a society where he has essentially no power. These humiliations lead to the deterioration of his mental state so that by the time he eventually murders Marie, the mother of his child, we are meant to understand that he was driven to do so by the broken society that shaped him. Or, as Jarcho’s Major (Kedian Keohan) puts it, “Nah, it’s not you. It’s the culture.”

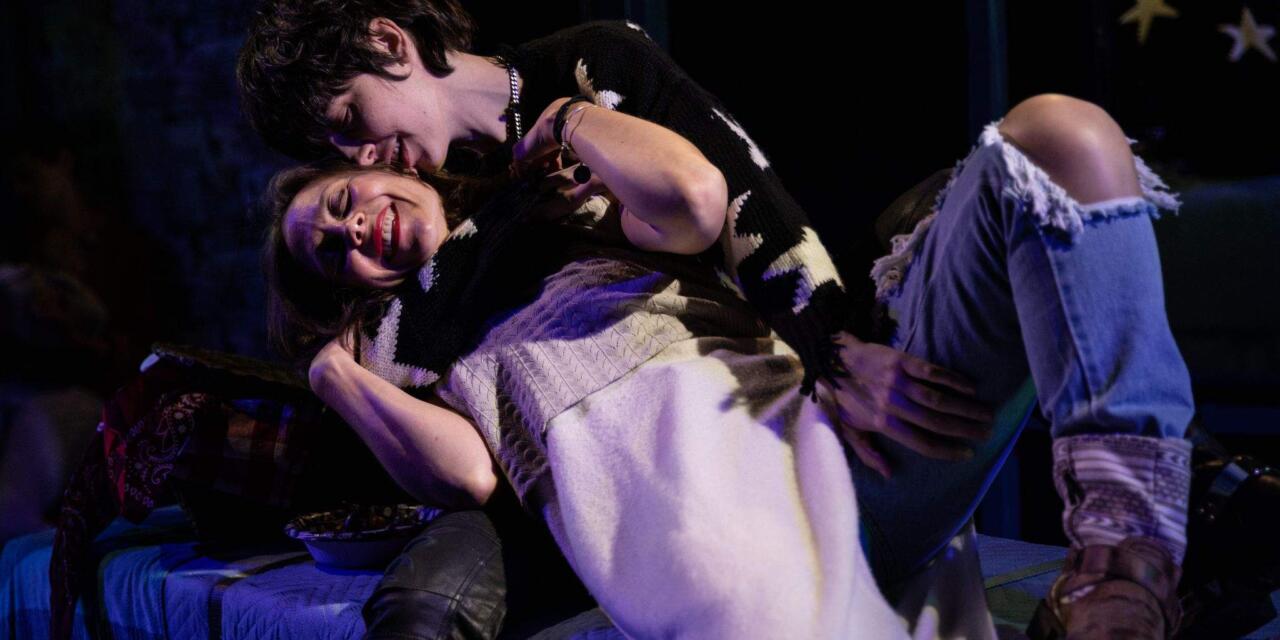

One argument for how Marie It’s Time, developed by Minor Theater and now playing at HERE, stands apart from other boy-kills-girl plays is that unlike much of the theatrical canon, it’s about the girl. Marie is spread across three bodies, those of Jennifer Seastone, Julia Jarcho (in her first time acting in her own work), and a bundle of blankets that stands in for both Marie’s baby, and Marie herself. The dueling Maries volley between berating and celebrating each other/themselves saying in one breath “I’m a worthless whore” and in the next “I look tasty (…) and anyone would be lucky to touch me”. Sometimes one Marie feeds the other lines and she dutifully follows, in part as a meditation on how we enact our desires through others, in part as an exploration of an author’s relationship to character. Sometimes the other Marie will disobey and hijack the action for herself. Either of the two could at any point be interrupted by the grating screams of the third (sound by Ben Williams and Elliot Yokum). All told it presents an image of uncertainty, fragmentation, desire, and repulsion all wrapped up together.

PC: Maria Baranova

Jarcho’s Marie is drawn to violence, at times hungry for it. It’s unsettling, but Jarcho seems to have a stake in exploring Marie’s desire thoroughly, and without apology. The night I attended there was a talk back during which Jarcho said something along the lines of ‘sometimes I feel the only way to survive femininity is masochism. Once there is sexual difference, there is already violence, so you have to try really hard to eroticize your condition or else how do you get out of bed in the morning?’ I struggle with this analysis because it seems to accept a certain level of doom. Why eroticize your condition instead of trying to change it? At the same time, I’m reminded of anthropologist David Graeber’s definition of direct action as “the defiant insistence on acting as if one is already free.” Can Marie’s eroticization of her own subjugation be seen as a bold act of direct action and a fraught attempt at survival in an unjust world all at once? Does my discomfort condemn her rightfully earned agency and erotic joy? How does the role of motherhood complicate, necessitate, or worsen Marie’s strategies?

Though this show does not engage with race, it brought to mind Jennifer C. Nash’s 2014 book The Black Body in Ecstasy: Reading Race, Reading Pornography in which Nash endeavors to “use racialized pornography as a tool for shifting the black feminist theoretical archive away from the production and enforcement of a ‘protectionist’ reading of representation, and toward an interpretative framework centered on complex and sometimes unnerving pleasures.” Jarcho seems to do the same for gender, making room for Marie’s “complex and sometimes unnerving pleasures”. It’s in this way that when one Marie says to the other “Look at you acting like it’s your body”, she can mean it as warning, condemnation, and celebration all at once.

Clearly there is richness in the ideas and questions explored in the piece, but at this point I must confess I’m not sure how much of Jarcho’s project I would have understood were it not for the ensuing talkback. I went into the performance without knowledge of Woyzeck or Minor Theater’s previous work which, as I understand it, often deals with similar themes. My immediate experience watching the show was often one of utter, and occasionally panicked, confusion.

This isn’t to say I didn’t enjoy myself. Marie operates on (at least) two levels with its heady theory floating above the deliciously queer, carnal, sexy, and funny performance onstage. The grungy songs were simple, but fun (music by Jeff Aron Bryant, lyrics by Jarcho) and captivatingly performed by the effortlessly cool Keohan as Major. I also loved watching Elliot Yokum on sound dance along to Keohan’s sirenic singing, one of many choices, alongside mirrors facing the audience (set design by Meredith Ries), and the use of microphones that reminded the audience we were watching a play, thus mercifully undercutting some of the brutality.

Ultimately Jarcho and Minor Theater’s seeming lack of concern for legibility is perhaps my biggest problem and greatest admiration of this work. When asked in the talkback what they thought the audience would take away from witnessing the murder Jarcho answer essentially ‘I don’t really think about that’. It caught me off guard because on the one hand, following one’s own questions fearlessly and with conviction seems to me a worthy project in its own right, but on the other hand, if that’s the goal, why have the audience at all?

And there’s still the whole boy-kills-girl of it all. Even director Ásta Bennie Hostetter, who normally does costume design, noted she initially felt trepidation about the project because of all the murdered girl characters she’s had to dress. Does the fact that there are no cis men onstage for this particular murder give it enough new layers to justify the retelling of a tired tale? Does it matter? I suspect the Minor Theater community, who describe themselves as “champions of weird desire”, have many varied answers to these questions and many related questions as well.

It’s a complicated, messy show, but so too is it a complicated, messy life. I will end on a quote from Andrea Long Chu’s Females (a tendentious book that also came up in the talk back). “Too often feminists have imagined powerlessness as the suppression of desire by some external force, and they’ve forgotten that more often than not, desire is this external force. Most desire is nonconsensual; most desires aren’t desired”. I admire the willingness of Jarcho and the rest of Minor Theater to brazenly explore their desires— even the undesirable ones.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Morgan Skolnik.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.