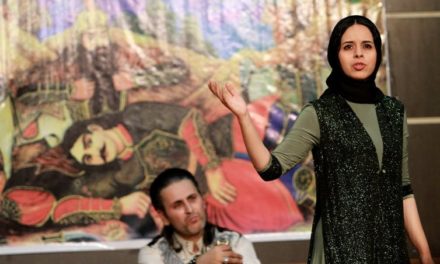

Aleena Karim interviews John Freedman, an acclaimed American critic, translator and playwright, on New Russian Drama, an emerging movement in Russian theatre famous for its ‘boldness.’

Aleena Karim: How would you define New Russian Drama in a nutshell?

John Freedman: As a term, then, the new drama is a knot of contradictions. In fact, it cannot be pinned down and, therefore, cannot be used precisely in a simple, descriptive way. None of that means that what took place under and around the banner of new drama was not a powerful, transformative force for Russian theatre. This we can state with certainty: the new drama movement exerted an enormous influence on theatre art. Russian theatre before and after new drama are two vastly different cultural spaces.

The new drama is probably best understood as a broad phenomenon that applies more to a time period than to any specific manner of writing. Crucially, the new drama era provoked vigorous, important, strategic and artistic arguments. It encouraged those who never thought about writing plays to become playwrights – one of the quintessential new drama authors, Yury Klavdiev, has said he thought theatre and writing plays were a boring pursuit until he saw a live performance of Vyrypaev’s Oxygen. The theory and reality of the new drama crusade inspired directors and actors who were fed up with the same old Chekhov-Ostrovsky treadmill to seek new avenues of expression.

AK: You said, in a previous interview given to Russia Beyond the Headlines that new drama “is just one part of the contemporary drama scene.” How would you elaborate this point?

JF: There are dozens – if not hundreds – of playwrights who do not consider themselves part of the new drama movement. In my anthology, I include one (Maxim Osipov) and I explain why. As I write in the book, even many writers like Nikolai Kolyada or Oleg Bogayev, whom we might think are close to new drama writers – reject that notion outright. Nadezhda Ptushkina, a very popular playwright, has nothing to do with ND. Older writers such as Alexander Galin have nothing to do with it, although his plays are performed in many theatres.

AK: What is your stance on the use of obscenity in the new drama?

JF: The use of obscenities was very necessary for new dramatists. They were out to break down barriers, to defy taboos. They wanted to achieve a new level of freedom in expression, in the possibilities of texts written for performance. They wanted to avoid “literary” forms and come as close as possible to “natural speech.” That meant that obscenities had to become a part of the new stage lexicon.

AK: How does a common Russian man (not elite) react to the portrayal of violence in every possible way?

JF: There is definitely a resistance to violence and to obscenities among average theater-goers. There is resistance even among many in the “elite,” as you put it. The general phrase one can often hear is, “I come to the theatre to see something out of the ordinary, but you show me what I have to see and hear every day in my life. I don’t have to come to the theatre to see that and I don’t want to.” That is a perfectly legitimate response. But it is the response of someone who has a very different goal (to be ‘raised up,’ to see something beautiful and exalted) from the playwright or director who is seeking to understand the workings and the essence of life as we live it here and now. There is another “problem” with violence on stage, which is surely true in all cultures, not just Russia: In theatre, we are very close to living people imitating characters. When there is violence right in front of us, two or three feet away from us – even when we know it’s not “real,” it is much harder to take than when we see it in the distanced form of a film.

AK: Why do you think that new drama needed that idiosyncrasy? Is it quite influential?

JF: New drama, as I have said, was an attempt to discover “real speech as people speak it.” It was an attempt to get rid of “literature” in theatre. It was never a choice to be “idiosyncratic” for the sake of “idiosyncrasy.” It was a search for a certain reality, which some people in the public then perceived to be idiosyncratic or, worse, hostile. The influence of new drama has been very strong. First, many of the “new dramatists” began working in film as directors or screenwriters. This brought about several very interesting independent films – those by Vasily Sigarev, for instance, or those by Valeria Gai-Germanika, who works with Yury Klavdiev. Mikhail Ugarov (director) and Yelena Gremina (screenwriter) recently released their film of “The Brothers Ch” about the Chekhov family – this is an outgrowth of the new drama movement, a development in a more sophisticated, but still, very down-to-earth style. Theatres who do not stage new drama plays have been affected at times, too. For a while, at least, one might see older plays staged in the manner of new drama plays – bolder, more challenging in their forms. Still, the new drama was never “popular.” It has been influential and will continue to be, as it develops. But it was not a mass movement.

AK: What impact have you seen on society as a whole of depicting real life issues in drama?

JF: I cannot prove this yet, and I may never be able to prove it, but I feel very strongly that the new drama, as practised at Teatr.doc especially, had a significant impact on the young generation which a few years ago began Russia’s most serious protest movement in a long time. I’m talking about what occurred between 2010 and Putin’s reelection in 2012. During those two years or so the protest movement exploded. It went, literally in a matter of days, from 500 on the streets to 8,000, and then to 50,000. Now, neither Teatr.doc nor new drama did all that. But for a decade or so, new drama and Teatr.doc worked to form opinions and energize people with a concern for social and political issues. For years it was impossible to get more than 500 to participate in protests or demonstrations of any kind. Then, all of a sudden, without “warning,” 8,000 showed up when Alexei Navalny called people out to protest unfair elections for the Moscow City Duma in early Dec. 2010. Just a week later over 50,000 people showed up at another rally. This continued for nearly a year, with crowd sizes sometimes growing as much, perhaps, as 100,000 or more, until the great crackdown that took place on May 6, 2012, the day before the inauguration of Putin to a third term. Since then protests have been smaller and not as frequent. I mention all this to give you a brief snapshot of the protest movement. Those who began to protest were predominantly young – pre-30 – and they were clearly educated. This is precisely the audience of Teatr.doc and new drama. Someday someone may find more concrete evidence of my belief that new drama and Teatr.doc fed the protest movement, but for the time being, we will have to settle for my intuition and my powers of observation. I don’t believe I’m wrong.

AK: What challenges does the Russian drama fraternity face for being daring like funding, publishing or staging issues? I also heard of Putin’s ban on foul language in literary genres…

JF: Yes, the challenges for new drama and anything like it are very strong right now. Yes, a law went into effect this summer banning the use of obscenities on stage. Most state-funded theatres either removed obscenities from their plays or removed entire plays from their repertories. Teatr.doc, which is a private theatre, defied the ban and refused to remove anything from any of its shows. The Moscow Art Theater, interestingly enough, although it is very much an establishment theatre, refused to remove obscenities from one long monologue in the play Playing the Victim by the Presnyakov brothers. I know that Gleb Cherepanov’s production of I Wish to Speak at the Chambers of the Nobility (text by Kira Malinina), has also refused to remove “offensive” words even though they were asked to. As for publishing, there was a boom in publishing plays 10 or so years ago, but that passed. Very few plays are published anymore in books – not because of new laws or because of politics, but because there is not a market for them. They are still published in magazines (Teatr, Sovremennaya dramaturgia) and, of course, on the internet. There is a new internet journal that publishes lots of plays – Dramaturgiya. There are some signs that traditional theatres, which occasionally flirted with new drama from time to time, have lost their interest. Pavel Rudnev recently wrote a post on FB about how new plays are entirely absent in this year’s nominations for the Golden Mask awards.

Aleena Karim is a researcher from Pakistan who is currently investigating New Russian Drama. She completed her BA dissertation on the prevalent trends in New Russian Drama in the light of Michel Foucault’s Genealogy.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Aleena Karim.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.