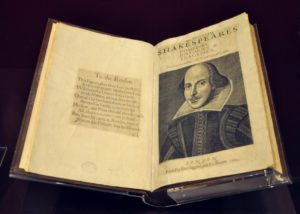

The recent discovery of a First Folio in St. Omer, France brings the total number of known copies to 233.

Photo Credit: Victoria and Albert Museum, London, National Art Library

The Shakespeare First Folio (1623), the first collected edition of his plays and the sole source for half of them (including Macbeth, Antony & Cleopatra, All’s Well, As You Like It, and The Tempest), is one of the most valuable books in the world: Paul Allen, co-founder of Microsoft, recently paid $6 million (US) for a copy.

The unexpected discovery of a Shakespeare First Folio in the public library of a northern French town has raised questions about how many were originally printed (estimated to be 750), how many still exist (now 233), and how often such books come to light. If recent history is any guide, the answer to the last question appears to be once every six years.

In 2002, Lilian Frances Cottle of Tottenham, North London died intestate and a tattered copy of the First Folio was found among her effects. In 2008, an unemployed, self-described ‘fantasist’ named Raymond Scott walked into Washington, D.C.‘s Folger Shakespeare Library with a copy that he claimed to have acquired from one of Fidel Castro’s bodyguards. The First Folio in question turned out to have been stolen from Durham University, and the flamboyant Scott – who arrived at his trial in a horse-drawn carriage, dressed in all white, holding a cigar in one hand and a cup of instant noodles in the other, while reciting lines from Shakespeare’s Richard III – was convicted of the theft and imprisoned).

And in the most recent discovery, exactly six years later, Remy Cordonnier, a librarian in St. Omer, France, identified a miscatalogued collection of Shakespeare’s plays as an original First Folio. The book had been housed in the library of the Jesuit College of St. Omer for centuries before being inherited by the town’s public library. But because it was lacking the title-page and had no identifying title on the binding, it had long been assumed that it was a relatively worthless reprint, until Cordonnier took an interest in the volume and called me in to authenticate it.

For more than a century, considerable effort has gone into determining how many copies of this rare book still exist. In 1902, the British scholar Sidney Lee published a book – Comedies, Histories, & Tragedies: A Census of Extant Copies – that rightly claimed to be the “first systematic endeavor to ascertain the number and whereabouts of extant original copies of the Shakespeare First Folio.” Lee located 152 copies and was later knighted for his efforts.

The tireless legwork of British folio-hunter Anthony James West in the 1990s led to the discovery of 80 more copies. In our 2012 census, The Shakespeare First Folios: A Descriptive Catalogue, West and I gave an extensive account of the 232 copies known at that time, relying whenever possible on firsthand inspections by ourselves or our research associates.

Curiously, though, several copies recorded by Lee have disappeared since 1902. During the Great Depression, a copy was filched from Williams College by a New York shoe salesman (who ultimately returned it in a drunken stupor because he was worried that it might fall into the hands of Adolf Hitler). Another copy stolen from Manchester University in 1972 has never been recovered.

Although the theft of institutional copies is generally well publicized, a few privately owned First Folios have quietly vanished. Despite two decades of searching, our research team could find no trace of the copy that had belonged to Major-General Frederick Edward Sotheby of Northamptonshire (which had been in the Sotheby family since 1700). The title-page from the copy owned by Ross R. Winans, Esq., of Baltimore somehow found its way into the First Folio now at Carnegie Mellon University, but the Ross folio itself has vanished.

The copy owned by Lord Zouche of Parham was sent to the British Museum for safekeeping in 1900, and the librarian confirmed to Sidney Lee that Zouche’s “folio Shakespeare is here with his books of which we are taking care.” They did not, it seems, keep a watchful eye over it: the copy has since gone missing.

And six years after Lee published his census, the novelist Thomas Hardy wrote to inform Lee that “Mr [Alfred Cart] de Lafontaine, my neighbor in Dorset, is the fortunate possessor of a 1st Folio Shakespeare, which he would like to show you. Your opinion upon it will be highly valued by him, & of great interest to me.”

In 1899, the same Alfred Cart de Lafontaine had given a talk about the recent restoration of his manor to the Dorset Natural History and Antiquarian Field Club. His audience, gathered “under the shade of a fine cedar,” heard Lafontaine detail the work he had done to the house and gardens; he described the long gallery or library, and singled out its two most precious items: “a pair of boots worn by King Charles I when a boy” and “also a very fine folio Shakespeare.”

Despite these written records, Lafontaine’s copy has never been traced.

So while the discovery of the St. Omer copy has added to the number of known copies, one can only regret that at least a half-dozen have somehow slipped through our fingers.

Then again, there’s always the chance that six years from now, one of them will turn up.

This article was first published on www.theconversation.com. Reposted with permission. Read the original here.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Eric Rasmussen.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.