An Interview with Iranian Director Mohammad Aghebati

Most young Americans would be hard-pressed to name a major artist or performer working in the Middle East today. In fact, the most visible recent “performances” staged in the Middle East have been the gruesome beheadings captured on video by ISIS. Individuals in the region who lack the megalomaniacal tendencies of the Islamic State are rarely heard by the Western press. Meanwhile, true cultural exchange is increasingly difficult; art and artists, already low on the US government’s list of priorities, seem to be considered trinkets we can’t afford to trifle with when faced with the kind of brutality we now see in the region.

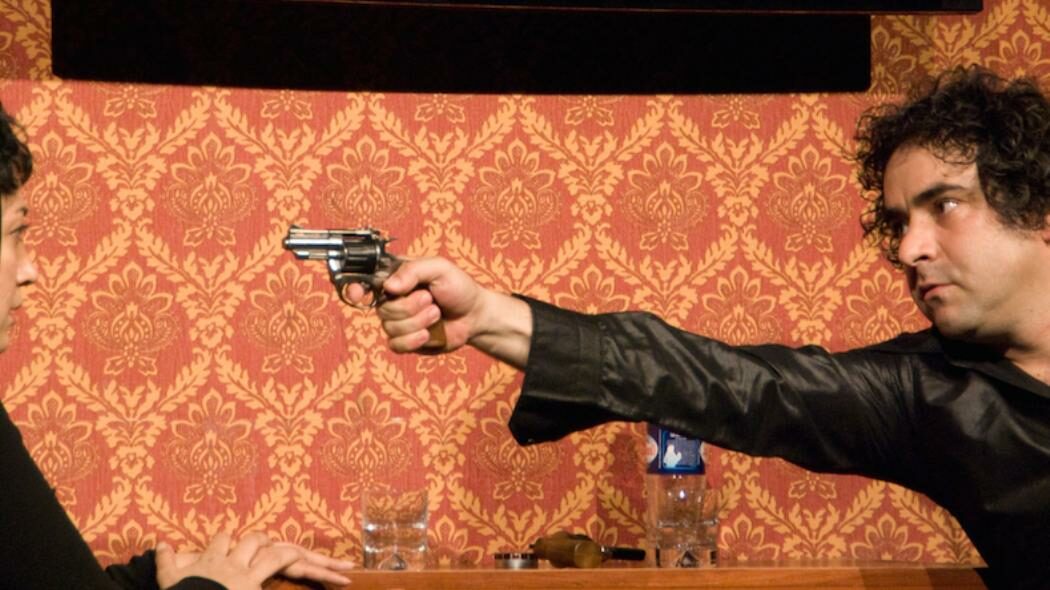

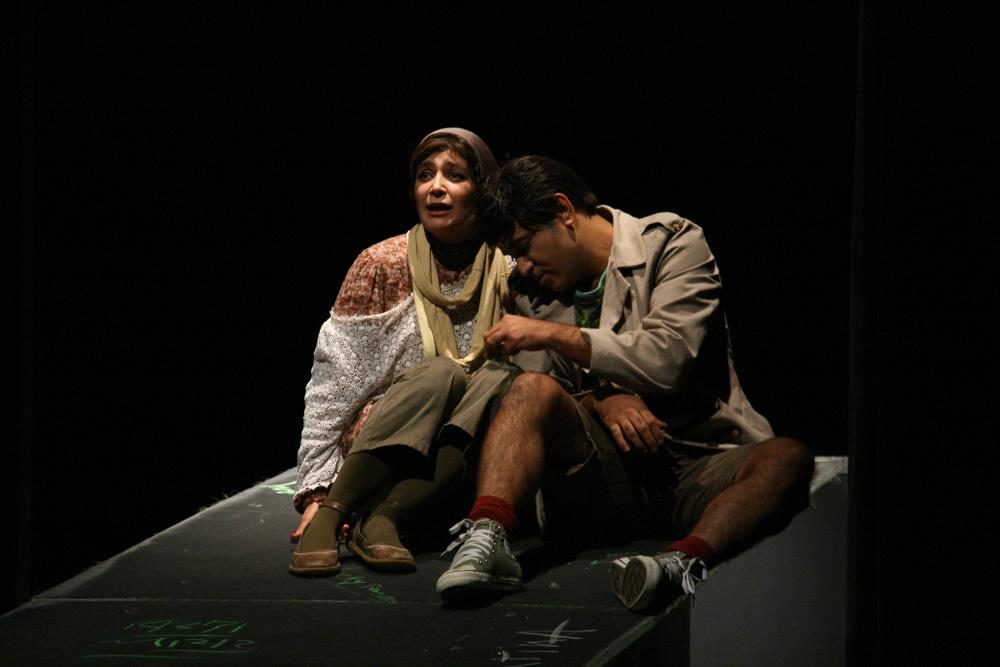

Iranian theater director Mohammad Aghebati feels differently. Born in 1975, his childhood coincided with the Islamic Revolution and the eight-year-long Iran-Iraq War that followed. He now splits his time between Tehran and New York, making theater in an attempt to work through the traumas of the Middle East’s particularly grisly recent history. International touring is a standard part of most major theater artists’ careers, but it’s not so easy for those from countries formerly designated as part of the so-called “axis of evil.” For Aghebati to share his work with the US, the country that perhaps needs to see it most given our ongoing deleterious involvement in the region, he faces a set of obstacles many artists would find insurmountable. VICE spoke with Aghebati recently to talk sanctions, censorship, and what it means for an artist to be a “rescue dog.”

Jessica Rizzo: What can you tell me about the new project you’re working on in Tehran?

Mohammad Aghebati: I’m working on a production of Richard II in collaboration with Mohammad Charmshir and Afshin Hashemi. It’s a free adaptation of Shakespeare’s play in the form of a monologue, and it’s inspired by current events in the Middle East. The Middle East today conjures up images of inadequate leaders, bloody power struggles, sectarianism, extremism, and the destruction of countries in the flame of war. These are the images we are working with as we reinterpret Shakespeare’s tragedy. This is a different and very difficult project for our group, but we hope that by the end of this year we’ll be able to take it to New York.

Jessica Rizzo: You’ve adapted a number of classics of Western dramatic literature (Hamlet, Oedipus). Do you see yourself as blending a variety of theatrical traditions? Are there forms of traditional Persian theater you feel particularly connected to?

Mohammad Aghebati: There are elements of traditional Iranian theater like oral storytelling, and the acting methods, and Naqali in Taazieh that I find pretty modern and exciting. But I’ve never been interested in limiting my work geographically. Theater provides a chance for dialogue between cultures. A dramatic heritage belongs to everyone. It allows us to transcend time, place, and language. The practice of adaptation is common here because it helps Iranian artists get around censorship, as you can claim that the story you’re telling is someone else’s story, not a story about Iran, and therefore not a story that needs to be scrutinized, not a story that would be of any concern to the government. Often, it is the local and native theater that attracts the attention of the authorities because they worry about anything that might undermine their power.

Jessica Rizzo: As I understand it, all books and films in Iran are subject to strict censorship, and foreign works are often altered to conform to Islamic standards of correctness as interpreted by the censors. For example, it would be considered indecent for a woman in a film to say “I love you,” to her partner, so the dialogue would be changed. If it concerns sex or politics, it’s not making it through. The film director Mohsen Makmalbaf has been quoted as saying that “Anything that makes people think is censored in Iran.” Do you agree? How does censorship impact your work in the theater?

Mohammad Aghebati: I feel censorship exists in one form or another and in different levels everywhere. It also exists in Iran, but to think that people cannot express love in a movie is an exaggeration. Censorship is based on both politics and religion, and political censorship is often susceptible to change in ways that religious censorship isn’t. Challenging censorship, treating it as an obstacle to be overcome has led to a special type of art and aesthetics. The audience is very familiar with what can and cannot be shown or said, and it creates an unspoken dialogue between the audience and the artist, an indirect dialogue.

Jessica Rizzo: How would you compare the theater/arts scenes in Tehran and, say, New York City? What role does theater play in the lives of young people? Many more theater artists and producers in Tehran are young. Almost 75% of the audience is made up of young people, often university students. Therefore you have passionate artists and audiences who are not so much concerned with the commercial value of the work, but rather crave an art form that can catalyze new ways of thinking, that can offer an alternative to the government-approved media. In Tehran, it’s often the plays that are the most original and audacious in form and content that are the most successful.

Mohammad Aghebati: What I’ve seen in the US though is that while in Tehran the government is our biggest obstacle, you’re equally constrained. It’s just that American theater makers are primarily constrained by the financial difficulties they face. But both situations hold artists back.

Jessica Rizzo: Over the past few years you’ve done some traveling back and forth between Iran and the US to study and to tour your work. During that time, relations between Washington and Tehran have been, at best, tense, and often downright hostile. What are some of the challenges you’ve faced as a result of the ongoing political situation? Have you been personally affected by US-imposed sanctions?

Mohammad Aghebati: I believe that the fires caused by politicians always end up burning the poor people who had nothing to do with starting them. Every day I see the pain caused to ordinary Iranian people by the sanctions. These pressures, the terrorist accusations, and the constant threat of war keeps producing more tension and anxiety for people who are also struggling with domestic problems within Iran as well. The people of both countries have a better understanding of peace and security of the region than those of the politicians in power. Unfortunately, in the midst of all this chaos, the artists suffer. They’re cut off from each another and their work is stuck in the middle of this animosity. This is worst when you go back and forth between the two countries. I personally experienced the anxiety when I had to deal with securing a visa for one of my actors. I was lucky that he was able to get his visa just before the show, but no matter how well-known and respected you are, if you are an Iranian there are full background checks that take forever. That’s always a challenge. In the past few decades some prominent artists have not been able to travel to festivals abroad because of these issues. Many students have not been able to continue their studies abroad, and something as simple as a flight can become a scary problem.

Jessica Rizzo: Do you consider yourself a political artist?

Mohammad Aghebati: I have never wanted to be labeled a political artist. I simply try not to be fooled by clichés and propaganda. I try to look at the world around me through a different lens, to pay attention to issues that others might not notice. I worry about those who might otherwise go unseen. Like a rescue dog, I have to follow my nose, react to the scent of life. Before calling myself a political artist, I have to honor my obligation as a human.

reposted with permission from VICE.com

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Jessica Rizzo.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.