It’s a grey April evening in northern Italy, near the Slovenian border, when Hong Kong actor Anthony Wong Chau-sang steps onto the stage of the Teatro Nuovo Giovanni da Udine. He is here to collect a Golden Mulberry Outstanding Achievement Award from the Far East Film Festival, returning to Udine 21 years after he attended the inaugural festival as the star of Gordon Chan and Dante Lam’s Beast Cops. When asked if he recalled what brought him to Udine that first time, his reply is self-deprecating. “Oh, I can’t remember. It was probably terrible,” he says. “I’ve made a lot of crap movies in my life.”

That may well be the case: Wong has over 200 acting credits listed on the IMDB. But as the elder statesman of Hong Kong cinema—its Robert Redford, to use a Hollywood analogy—he is allowed to have a few turkeys in his repertoire. Redford counts Legal Eagles and The Horse Whisperer among the 81 credits he accrued in a career twice as long as Wong’s, so any missteps are forgivable.

Contrary to his boisterous screen persona, Wong is soft-spoken and cautious. His first responses tend to be clipped: a “Yes, why not?” here and a “No, I don’t think so” there. He is polite but careful with his words. Recently, he has garnered fresh attention from newcomers and overseas audiences as the star of 2019’s local sleeper hit Still Human while earning the wrath of Beijing for publicly supporting the Umbrella Movement in 2014. But for Hongkongers and Hong Kong movie buffs, Wong is one of cinema’s most recognizable faces.

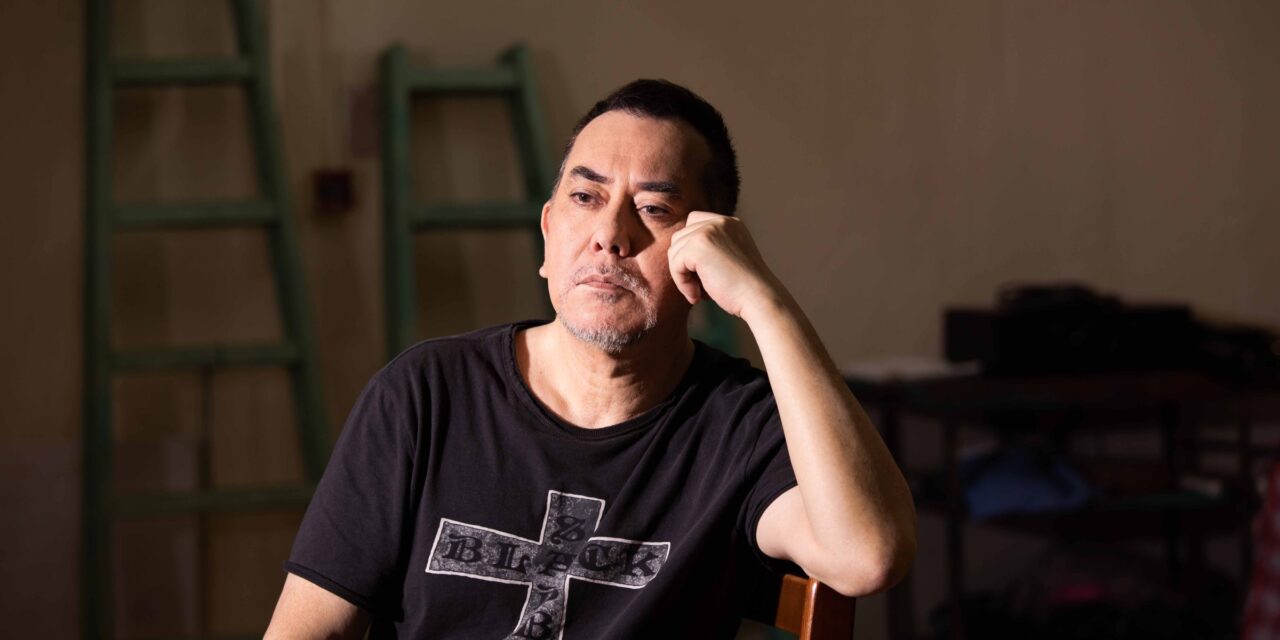

Anthony Wong in Wind Mill Grass Theatre’s Tsuen Wan rehearsal space – Photo by William Furniss for Zolima CityMag

Now 58, the Wan Chai native has created some of the industry’s most indelible characters. There is the lascivious spirit Wu-tung in Peter Ngor’s 1991 Category III classic Erotic Ghost Story II; psychotic murderer Wong Chi-hang in Herman Yau’s notorious 1993 black comedy The Untold Story (which nabbed Wong a best actor in Hong Kong Film Award); and the nuanced biopic Ip Man: The Final Fight in 2013. Other standouts include playing an activist priest in the turbulent 1970s in Ann Hui’s 1999 drama Ordinary Heroes; a stoic inspector in Andrew Lau and Alan Mak’s reinvigorating Infernal Affairs trilogy (2001-03); and assassins in Johnnie To’s bullet ballet landmarks The Mission (1999) and Exiled (2006).

Since his 1985 debut in Angie Chen’s My Name Ain’t Suzie, Wong has worked with industry giants Derek Yee, Ringo Lam, John Woo, Tsui Hark, Sylvia Chang, Pang Ho-Cheung, not to mention Rob Cohen on a genuine Hollywood blockbuster (The Mummy: Tomb of the Dragon Emperor). And that’s only the tip of the iceberg.

It’s that diverse body of work that won Wong the accolade in Udine, Europe’s most influential Asian cinema event since 1998. As part of the recognition, Udine screened Suzie, in which Wong plays the love interest, Jimmy, the abandoned child of an American sailor who goes from black sheep to businessman. He regaled the rapt audience at the follow-up panel with stories of how he spoke no English at the time of the shooting and how, as he put it, “I realized I knew nothing about acting.” Then Chen chimed in with a summary of what has made Wong such a stalwart fixture in Hong Kong films. “What I think he meant was that he was a natural,” she said. “He didn’t consciously try to act. He just played himself, and I think that made the movie. All the anger and all the angst just came out, without pretense.”

Still Human co-star Crisel Consujin echoed Chen earlier, stating, “He’s very intelligent, and he strikes me as someone who doesn’t do BS. He knows what he wants and he shares what he thinks. I really respected that. You could tell he was doing the film because he believed in what it was going to do, not just from a creative standpoint.”

Like Jimmy, Wong was born to a Hong Kong mother—an opera singer—and a British RAF pilot who left the family when Wong was still a child. (With help from the BBC, Wong reconnected with his father’s side of the family last year.) Wong has always been frank about growing up poor, a frankness that has carried over into his film career. He is known for raising a critical voice that has given him a reputation for being “difficult,” a word that many consider to simply mean honest.

“So many older filmmakers told me not to work with him, one reason being the film wouldn’t play in China,” says Still Human director Oliver Chan. “Another was that he could be a ‘difficult artist.’ I still thought I should ask him. I thought he was great for the role and the film.”

Chan was vindicated when Wong earned rave reviews (and another HKFA) and the film scored nearly HK$20 million in box office receipts. The film tells the story of Evelyn, a domestic helper played by Consujin, who is hired to take care of a disabled, irascible man played by Wong. Convincing him to take the part was simple. “He liked the script and I got the impression at this point in his career he wanted to help young filmmakers and try something different,” says Chan. “He jokes about making many bad films, but he’s made so many he winds up repeating his roles.” This offered him something fresh.

Wong agrees, but adds, “Most importantly it was the first time a film revolved around a Filipino maid. That should have happened a long time ago.”

Wong stumbled into acting as a favor, by accompanying an anxious friend to an audition for a television station training program. That was the best way to train as an actor until the early 1980s when the Academy for Performing Arts opened. “I got in, he didn’t,” says Wong. “I didn’t know anything about acting at the time, and acting had a terrible image. But within the first week, I fell in love with it. Later, I signed a contract with ATV, and then I studied at the APA for three years. That was the happiest time of my life,” he says. He followed the great Hollywood actors of the era closely, naming Robert de Niro, John Hurt, Meryl Streep, and Malcolm McDowell as actors whose work he particularly admires.

In 1984, Wong’s friend and collaborator Herman Yau put him in touch with Chen’s production crew, which set him on his current path – however rocky it has become. According to a 2017 report by Taiwan’s Apple Daily, Wong, along with comedian Chapman To, and singers Anthony Wong Yiu-ming, Vivian Hsu, Denise Ho, and 50 other artists, has famously been “blacklisted” from working in China because he voiced his support for the 2014’s Umbrella Movement. As a result, given the weight film distributors place on general releases in China, his career has stalled. “No one’s coming to me right now,” says Wong.

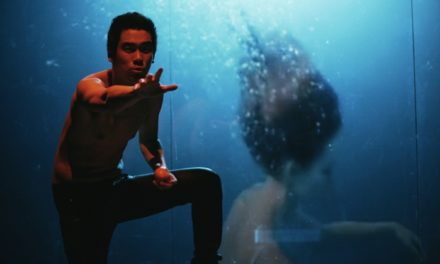

Joey Leung and Anthony Wong in Wind Mill Grass Theatre’s rehearsal space – Photo by William Furniss for Zolima CityMag

Back in Hong Kong, Wong is more relaxed, less guarded and quicker with small talk and a quip. He read all the Game of Thrones books and watched the entire television series, happily sharing his verdict on the controversial final season. “Terrible,” he says, followed by a dismissive tsk. And contrary to what he said in Udine, directors and producers are indeed coming to him, the latest being Joey Leung, co-founder and creative director of Wind Mill Grass Theatre.

Six weeks after returning from Italy, Wong is perched on a sofa in Wind Mill Grass Theatre’s Tsuen Wan rehearsal space, preparing to get to work on his second theatrical performance in a year; he previously starred in his own Dionysus Contemporary Theatre’s Sunset Warriors in 2018. Leung and Wind Mill Grass Theatre co-founders Edmond Tong and Luna Shaw chose Larry Kramer’s timeless and timely AIDS drama The Normal Heart for their next project. “The Normal Heart is one of my dream plays,” explains Leung.

In the play, activist Ned Weeks (Leung) is one of many conflicting voices debating how best to force action for the largely ignored health crisis. “I don’t think it’s just a ‘gay play,’” he says. “It’s about equality and human rights – and gay love. It’s about how to fight for something you think is right even though the rest of the world thinks you’re wrong. And it’s about anger, and how to use your anger, don’t lose it, and use it with patience and compassion and forgiveness. And this is Hong Kong now.”

In Hong Kong, auditioning for small theatre productions is rare, so when casting Heart, Leung put Wong at the top of his wishlist for the role of Ben Weeks. As the only straight character in the play, Wong has the unenviable task of spewing some unenlightened views while somehow keeping Ben human. As Ned’s lawyer brother, Ben is passively supportive of Ned’s radicalism but ultimately reveals his homophobia.

Leung describes needing a complicated authority figure that people would respect even if he trod on the hateful territory. The potential for the bump in ticket sales from Wong’s name wasn’t a factor. “Definitely not,” says Leung. “I’m quite a strong presence on stage, so I had to find someone stronger than me, and that’s not easy sometimes. [Wong’s] will be the character saying out loud words that sound normal but are actually twisted – even though he doesn’t think so. [Ben’s] not a bad person and Anthony has the qualities that make you understand him, even if you don’t agree with him.”

When Wong hears that, he responds with a perplexed grimace. Is he complicated? “Yes I am,” he nods. Possessing authority? He pauses for a beat, frowning pensively, and replies, “Sure.” Is it not a bad person? “Absolutely I’m a good guy,” he says with a laugh. “I don’t know where this comes from. Perhaps experience from all these years. Maybe it’s my personal character. I know I have these qualities but I don’t know what creates them, or how they developed, and how it’s perceived is for audiences to decide.”

Did Wong worry about starring in a “gay” play? “Why would I care?” he replies, shaking his head at the idea of his peers’ resistance. “I don’t understand. Oh, it’s a gay play, it’s a woman’s play, it’s a children’s play. What? I never think about those factors when I choose a role. All I know is that I’m creating a new character. I don’t ask whether the audience is coming to see me, or what they expect from me. I concentrate on the work. It’s very simple.”

Despite Wong’s “situation,” as he refers to it, the industry hasn’t washed its hand of one of its best actors. He has made eight films since 2015, two television series—including White Dragon for the UK’s ITV and Amazon—and four dramas. And regardless of how it will be received in the mainland, To has cast Wong in the third in his acclaimed Election series, and he’ll feature in Steve Yuen’s Declared Legally Dead later this year. He is flirting with the idea of teaching an acting class.

Does he regret missing the opportunities China affords? “In the beginning, I did care,” he says. “Sometimes I miss the big-budget films, but you have to face reality. Other than for money, I don’t want to work in China. I never got used to it – the lifestyle, living in a hotel, the air. I don’t think I could ever melt into the culture. And the work wasn’t even really worth it.”

Wong is sanguine on most subjects and turns philosophical on a dime. While he has stated in the past that Hong Kong cinema is dying, he supports young filmmakers (he worked on Still Human for next to nothing), and thinks the industry is in the midst of remaking itself. “The new generation is completely different than what it was,” he says. “After [the handover in] 1997, the politics have made it completely different. But young filmmakers will create a new type of industry. The survival of the industry isn’t simply about money – it’s about culture. You need your own culture and your own stories.”

In the meantime, Wong is preparing for his role as Ben – a role he took without actually reading Kramer’s play. “I trust Joey,” he says. “He called me and I’m happy to have something to do.”

In parting, Wong considers his legacy. Redford will leave the Sundance Film Festival behind. How does Wong hope to be remembered? “That [I] was a good man. That [I] was brave. That [I] was an artist. I really don’t even dare to dream about that – and it’s really not important in the grand scheme of things,” he says. “We should show humility because compared to the scope of the universe nothing is important. We’re here. And then we’re gone.”

The Normal Heart runs 16 to 25 August 2019 at Kwai Tsing Theatre. The Cantonese production is supplemented with English subtitles.

This article was originally published in Zolima City Mag on July 25, 2019, and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Elizabeth Kerr.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.