To read Part 1 of this interview, click here.

TRANSLATION AND ADAPTATION

For the Illinois State University production, we wanted to change some of the characters’ genders to cast more female students—including the Owner. I saw that some Korean productions did the same, including Theatre Company Soo’s successful 2016 revival.

Yellow Inn has become a popular play for theatre programs. There are many versions and I haven’t seen them all. I think it’s fine to change the Owner into a woman.

With that change in mind, I started translating the play. But even though the lines were the same, I felt that the Owner and Wife’s relationship changed since they were now both women. I wasn’t sure how to move forward. The director and I then came up with the idea that the inn could be run by three sisters.

So the Sister-in-Law becomes the youngest sister?

Right. The play turned into a kind of fairy tale—the two wicked older sisters and the kind youngest sister. That led me to think about King Lear, which resonated strangely with Yellow Inn as soon as it came to my mind. I saw parallels between the two plays in terms of tone and worldview. Then I got to the scene where the Gravediggers sing the traditional Korean folksong “Ongheya” in the Korean source. I was stuck again. It didn’t feel right to replace it with an English-language folksong, and it didn’t make sense for the actors to suddenly sing in Korean. Since the Gravediggers do magic tricks for the guests right after this moment, I thought: what if they put on a little play instead? That’s the inserted scene that the director asked your permission about. The idea is that the Gravediggers present a bastardized version of King Lear that only shows the violent death scenes. I thought it could be a fun way to foreshadow the actual deaths later in the play, which are also over-the-top.

Well, I don’t intend to travel to the U.S. so do whatever you want with the play.

I wasn’t sure whether you would approve.

It’s always ambiguous where the playwright’s domain ends and the director’s begins. I think most playwrights these days are interested in seeing how a director picks up on elements of the play that the author was unaware of. A director could extend the play’s horizons by interpreting a character in a new way.

I’m relieved to hear you say that.

All I ask is that you include a note in the program that explains the changes you made. In any case, a play changes depending on the audience—whether they are Korean or American, whether it is the general public or a student audience. Who is in the audience is just as important as who made the work. For an American audience, it can be a good idea to change something traditionally Korean like “Ongheya” into something more familiar to them like Shakespeare. In fact, the central image of Yellow Inn refers to air pollution in Korea, but it can also evoke the landscape of the Gobi Desert. That image is not Korean at all.

Actually, some of my colleagues asked me during the season selection process whether this play is set in Korea. I told them that the setting could be Korea but doesn’t have to be. There are definitely Korean elements and a Korean sensibility, but there are few references to Korea in the dialogue.

In the play, the yellow dust is so bad that layers of sand pile up indoors. An American who has spent any time in Korea would immediately think, ‘Korea isn’t really like that.’ In general, my plays are more allegorical than culturally specific. I did write this play in response to generational conflict and economic disparity in Korea. So Korea was certainly the inspiration. But you may have noticed that the dialogue feels somewhat Western. I’m actually curious whether my play can reflect social and economic issues in the United States, such as racial tension, for example. When people refuse to understand one another, these conflicts can lead to extreme outcomes.

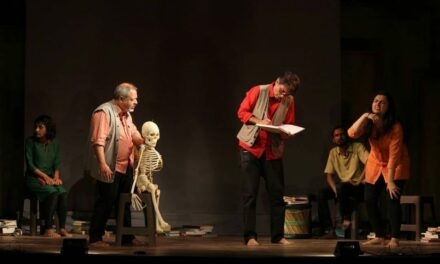

Yellow Inn, by Lee Kang-baek, directed by Koo Tae-hwan, Theatre Company Soo production (2016) Photo courtesy of Theatre Company Soo.

Yes, I think it’s getting worse. People don’t even see the same news anymore; you can pick and choose what you want. How can you communicate when you can’t even agree on basic facts? The area where I live has a largely conservative population, while Chicago and other urban areas in Illinois lean Democrat. Some of my students talk about political division within their families, especially with older members. I thought a lot about those students as I worked on the play. Also, the American media has been focusing on the generational divide lately through terms such as “baby-boomers” and “millennials.” I think that right now is an apt time to stage this play in the U.S.

Korea was traditionally a Confucian culture that emphasized respect for elders. But as Korean society changed rapidly, that entitlement for respect prevented the older generation from adjusting to change. Instead, they became stubborn people who failed to understand youth culture. Starting in the 1990s, Korean society was marked more by generational conflict than class conflict. That was a new phenomenon for everyone, both old and young. These changes made everyone anxious because no one knew what to do. At the time, many people—pundits, authors, sociologists—were pointing out that generational conflict was on the rise. They all highlighted the problem, but no one had a concrete solution. There still isn’t a solution. But these tensions have become more bearable in the sense that separation between generations has become the norm: “You live your life and I’ll live mine.” The problem can’t be solved so there’s no point in trying. People prefer to live disconnected from others. But that can’t be a peaceful solution. I think that the clash between conservative and progressive politics in Korea today is rooted in the generational division.

CENSORSHIP AND ALLEGORY

How did you become a playwright? What led you to pursue a career in the theatre?

From when I was young, I wanted to be a literary author. I tried my hand at novels and wrote a lot of poetry too. But I ended up winning the literary contest for one of the major newspapers in the drama category. The U.S. doesn’t have this literary debut system, but this is how you became a writer in Korea. It only exists in South Korea and Japan—actually, it has gone away in Japan as well. My debut play was staged. As soon as I saw the production, I fell in love with the theatre. I realized that theatre was what I wanted to do with my life. Since then, I have only written plays.

Were there any important political, social, or cultural events in your life that influenced your writing?

I would have to mention the April 19 Revolution of 1960, which was around the time that I finished elementary school. I experienced the revolution in my hometown of Jeonju. The following year, of course, had the military coup of May 16. My family had moved to Seoul in the meantime, so I was here in Seoul when Park Chung-hee seized power. These were momentous events in my childhood. A lot of the casualties during the April Revolution were in Seoul when the police fired on student protestors outside the presidential residence. In Jeonju, on the other hand, the main demonstration happened after the Revolution. While the media was broadcasting President Rhee Syngman’s resignation from office, the citizens of Jeonju ran out into the streets. Students and youths would lock arms and belatedly shout slogans demanding Rhee’s removal. I was struck by the irony of how a political demonstration could turn into a kind of festival. One of the youths had tied a cloth around his head dipped in red paint to look like blood as he marched down the street, shouting “Resign, Rhee Syngman!” even though Rhee’s resignation was announced that morning. Policemen on horses surrounded the mock-protesters. It was a celebration.

On the other hand, the May 16 coup started with a military parade supposedly in honor of the Revolution. The event was announced on the news, so a lot of people were out on the streets to see it. I was there too. I saw the tanks roll in, rattling the earth, followed by rows of soldiers in full gear marching in perfect step. When I saw the soldiers, a shiver went down my spine. These soldiers looked like they were ready to kill rather than participate in a peaceful celebration. As soon as they passed by, the crowds dispersed in fear.

When I was a refugee during the Korean War as a young child, I contracted polio from contaminated water. As a result, I developed—how can I put it—a kind of skepticism towards the idea of the group because I was often excluded. During sporting events at school, I would be responsible for keeping watch over everyone clothes after they changed into their uniforms. There were almost no games that I could play with other children. My debut was in 1971, which is also when the Yushin System was instituted. It’s strange to think that I became a playwright just as the military dictatorship was tightening its grip on society. The Yushin System enforces the belief that it is honorable and necessary for individuals to sacrifice themselves for the state. Perhaps because I was used to being alienated from the group as a child, I developed a sense of resistance towards those who infringe on the integrity and dignity of the individual. I think that influenced my writing.

You mentioned irony when you described the scene in Jeonju during the April Revolution. The irony is predicated on distance. You have to stand aside to be able to see something in a different light. I wonder if the ironic tone in much of your work is connected to your thinking about the group and the individual.

Theatre can create that distance. Of course, things might look different from an actor’s perspective since the actor is participating directly in the performance. Some would say that the playwright also participates directly, but I think that we thrive on distance. To observe something already implies distance, even if the observer is up close. Ultimately, this ironic distance is what enables social critique. Don’t get me wrong—I’m not saying that a playwright can never be in accord with society. Rather, playwrights should try to place themselves on the outside of society, which is different from simply attacking it. Jesus said something amazing when Pontius Pilate asked him whether he considers himself the King of the Jews: “My kingdom is not of this world.”

Yellow Inn, by Lee Kang-baek, directed by Koo Tae-hwan, Theatre Company Soo production (2016) Photo courtesy of Theatre Company Soo.

Speaking of social critique, could you talk about what it was like to write during the Yushin period when the theatre was censored by the government?

I find that hard to explain sometimes. Theatre critics say after the fact that I chose to write in an allegorical style to avoid the censors. That’s partially right and partially wrong. Looking back, that might have been what happened. But on the other hand, I was never comfortable with realism. When I see realist theatre, I wonder, ‘How can this be real and theatrical at the same time?’ I don’t like theatre that makes claims to reality. To me, non-realist theatre feels more immediate. It speaks to the reality that we live in. Because of the aftereffects of polio in my childhood, I feel that my range of life experience is limited. No, maybe that’s also speaking after the fact. It would be more accurate to say that I was always drawn to idealism. That’s how my mind works. One of the things that Korean theatre artists misunderstand about Chekhov is treating his work as the pinnacle of realism, even though Chekhov himself denied it. I’m not trying to criticize anyone’s work, but I don’t think that representing reality is that simple of a matter. The audience has to already share your idea of reality for them to treat the performance as real. What if they don’t agree with how you see the world?

Returning to the question of whether I wrote allegorical plays to evade the censors, I would say that allegory came naturally to me. It’s undeniable that my plays stood out more when there was government oppression. You could say that allegory had a purpose in that period. Now that censorship has been abolished, allegory may no longer be self-evident. As a playwright who has relied heavily on allegory, I struggle with how to continue writing when allegory has lost its central purpose. I’m only kidding, but I got a lot of attention when there were censorship laws—not that censorship should continue just so that I can be in the spotlight.

Since there is always the possibility of your plays being misunderstood, as in Chekhov’s case, have you ever considered directing your own work?

Although I have physical limitations, I’ve thought about being on stage. But I’ve never considered directing. There is a playwriting textbook that I used, I don’t remember the title right now. In the first chapter, the author talks about how the English word playwright shares its etymology with the word wheelwright. A wheelwright makes wagon wheels. But if you make a wheel out of a solid piece of wood, it will rattle. You need space around the spokes for the wheel to bear weight and turn smoothly. The same goes for a shipwright. You need empty space for the ship to float. If you leave no space for the actors, director, and designers to enter the play, it can’t be performed. You can’t write a play like a novel.

A director is someone who fills in empty spaces. I am always amazed by playwright-directors who can take on both roles—even though they require opposite mindsets. When I taught playwriting, I would tell my students that they are filling in their plays too much. If you think that the reader will have a better experience if you fill all the gaps, you are wrong. There is no space for imagination. It’s not a drama if the actors can’t inhabit it. I’ve never considered directing because it’s a completely different function and I’ve never wanted to fill in the gaps.

Do you not go to rehearsals as well?

I don’t. Soon after my debut, I had the chance to see a prominent playwright who shall remain unnamed in rehearsal. Whenever the actors encountered a problem, they went to the playwright instead of the director. The playwright had elaborate answers for all of their questions, explaining this and that. I wondered how it was possible for him to do that. Even if he’s right today, things might change tomorrow. Would he be able to give the same answer the next day? So I try not to go to rehearsals. I don’t think that playwrights should. Of course, sometimes I regret it. If I had offered some thoughts about the play, it might have prevented production from completely missing the mark. But it does more harm than good. Also, even if I’m disappointed by a particular production, I tell myself that there will be other opportunities to stage the play with a different director and cast. Younger playwrights tend to struggle when production fails. They feel that the first production means everything. If you realize that there will be other opportunities, it’s less painful.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Kee-Yoon Nahm.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.