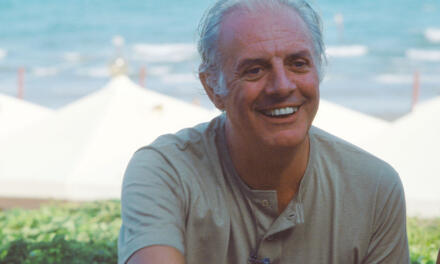

“While being respectful, I am not reverential,” says he, an Indian theatre director, screenwriter, and documentary filmmaker. Born in 1956, he worked with playwright and director Satyadev Dubey – winner of the Padma Bhushan, the third-highest civilian honor in India – for ten years, while having received no prior formal training in theatre. Shanbag founded the theatre company Arpana in 1985, and it has been lauded for strong performances with minimalist staging and experimental incorporation of music as well as design. Music predominates in his plays; he includes folk music traditions local to the people in the play, making it more authentic. He also co-founded Studio Tamaasha, an intimate space for alternate theatre in Mumbai, with Sapan Saran, in 2014.

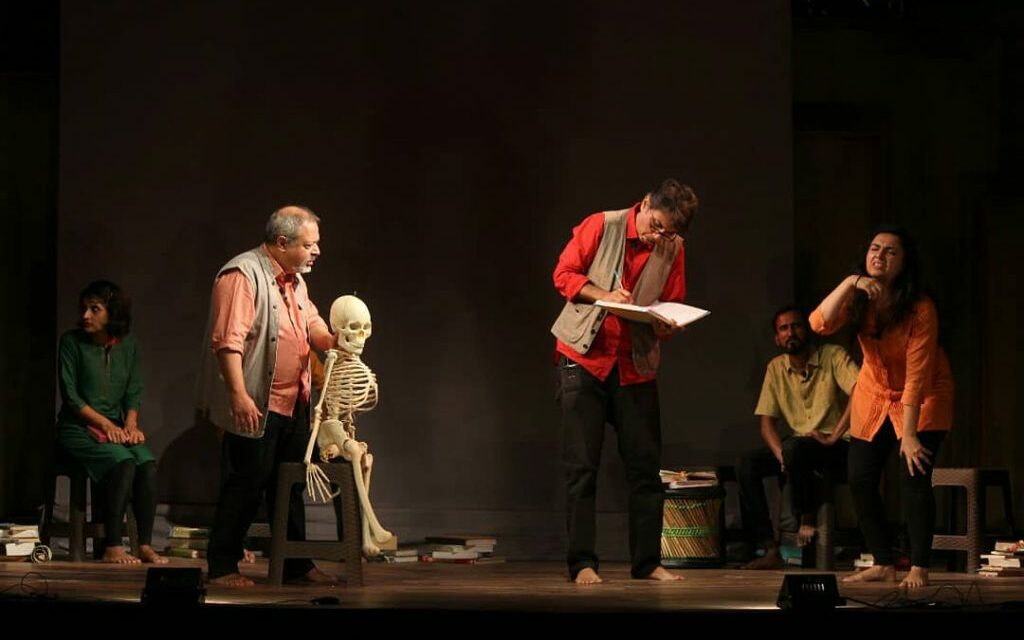

Shanbag and Saran visited Manipal Centre for Humanities in January 2019 and conducted a one-day acting workshop for the students on 22 January. They also performed their critically acclaimed play Words Have Been Uttered, a Studio Tamaasha production, alongside their other cast members, on 23 January.

This interview was conducted by Sania Lekshmi and Nidhi Panicker, who are students at MCH, on the afternoon of the 23, before the play was staged.

Sania & Nidhi: We will start with something regarding your early days when you founded Theatre Arpana. Without a formal background in theatre, how did you gather resources such as finance, space, et cetera and manage them and go on to fund your own theatre company?

Sunil Shanbag: I worked for about ten years with Satyadev Dubey, and during those ten years, I played many roles: I was an actor, director; I did light design; I worked with the set, and so on. So it was the kind of theatre company where you did everything, where you learned about all the various elements that go into making a play. At that point I was very comfortable; we had gotten complacent living in his shadow, so he actually had to tell us that we couldn’t work with him anymore. Thereafter, around three or four of us were told to get out and form our own company.

One of our members’ parents, who was a former member of the Indian People’s Theatre Association, offered us ten thousand rupees to get started. Now, this was in 1984, I think, so it was not a small sum then nor was it huge, but it was good seed money to get started. The kind of theatre we did didn’t really need much space as such; we only needed space to rehearse, and we had a rehearsal space in a college in the boys’ common room. We made plays for which all the materials could fit in one Maruti van, and hence they were very “light” plays. We didn’t have elaborate sets: we couldn’t afford them; we had no space to store them – so that was the kind of theatre we started out with. People started recognizing us for doing something different – we were very clever with our use of lights and sound; all these things colored our work quite differently and distinguished it from the work happening around us. That’s how we began.

S&N: So, coming to the regional theatre in India, when one moves out of that space it becomes a little challenging to understand that language. While adapting Shakespeare’s All’s Well That Ends Well to the Gujarati language (the language native to the Indian state of Gujarat) and context, is there any technique that you employed during the play or while adapting it, so that other regional audiences could also access it?

SS: Mihir Bhuta did the adaptation; he adapted it such that it would feel like an Indian play and wouldn’t feel like a Shakespeare play at all. The Globe commissioned this play: hence it wasn’t as though I chose this play; I would have loved to work with Taming of the Shrew, for instance.

I was to work in Hindi first, but the authorities declined, telling us that they had a large Gujarati crowd in Great Britain and they would love for them to come and see a Shakespearean play. Gujaratis there don’t usually come for a Shakespearean play in English, but when presented in Gujarati, they would come. Once they come, it would increase the probability of their coming again. Therefore, it was part of their audience-building exercise. They asked me if I would work in Gujarati and I agreed because I speak and know Gujarati, so there was no choice involved as such.

Having said yes, I knew that the play would have to have a life before the Globe and after the Globe. Regionally, audiences and their interests differ, so the play was adapted keeping in mind the kind of audience we would have.

We toured mainly Gujarat and Maharashtra. Later on, I realized that this play had a life beyond that. So I did a Hindi version of it two years later called Mere Piya Gaye Rangoon (which translates to My Lover Has Gone to Rangoon). In Gujarati, it was called Maro Piyu Gayo Rangoon (which also translates to the same as the Hindi title). That traveled quite extensively all across India. Language is indeed an issue when it comes to such plays; subtitling is one way of getting past the linguistic barrier, but many people don’t like reading while watching, so you really have to find other ways. And, the one time that we managed to do it was during a play I did many years ago, named Cotton 56 Polyester 84, which was about the mill workers and their state of oppression in the then Mumbai. The natural language of the play should have been Marathi (the language native to the Indian state of Maharashtra). But I said that there was no way I’d do it in Marathi because that would restrict me, and I needed to travel all over the country. Hence, when we translated the play – it was originally written in English – I got a Marathi writer who knew Hindi well enough to translate it, and I asked them to use the Marathi syntax.

I let all the songs in the play remain in Marathi. What happened then was very interesting. In fact, I remember we had already been performing it for about three to four years, and a young person came after one of our later shows and said that he had not realized that we did Cotton 56 Polyester 84 in Hindi because he had seen it in Marathi originally. I said there never was a Marathi production. He insisted that he remembered seeing it in Marathi, and it’s interesting that it had stayed in his mind as a Marathi play, although he saw it in Hindi. (The syntax of the language remained in Marathi – thus, associations will be made with the original language by the indigenous audiences, but by using a language that was widely used, it also traveled extensively.) This shows that you have to find ways to maintain linguistic authenticity. One way it is made possible, of course, is due to the fact that there are linguistically diverse audiences, but sometimes the flavor and the color of the original language is also critical to the play.

S&N: When you work with another playwright’s script, how much freedom do you think a director is allowed to take when it comes to that particular script, such that you can fulfill your vision and also do justice to the playwright?

SS: I believe there has to be a conversation since most playwrights are open to the director changing things around as long as the fundamental spirit of the play is not attacked. I’m very careful while choosing a play in the first place. It is not as though you choose the play and you think, “My God, now what do I do with it, let me change this and that.” I’m quite respectful of the original script. If there is a problem, I believe it is my duty to find ways around the problem. It is very easy to say “Cut this, cut that” because you can’t figure out a solution. You need to try very hard to figure it out, and if you can’t then perhaps you’re justified in making the change. While being respectful, I am not reverential, for me the script is not God. I’m respectful in the sense that somebody has put thought and effort into work, so we need to respect that. But it is very clear that I will be making the play in my own way, not in the proprietorial sense but in the sense that it will be my interpretation.

S&N: What kind of production team do you employ in your troupe?

SS: I think, for a young theatre company, everybody should partake in everything because that’s the way you learn, and it is important to learn. It is important for theatre to be a little more democratic because, as you said, people who work backstage are almost invisible. But then when you get to a scale where you are on parity with a larger production, then you have to have expert help. You cannot say “actors have to do everything”. What actors must do is not just throw their costumes on the floor and walk out; they ought to be respectful and put them on a hanger so that the person in charge of costumes can put them away. Internally, that’s how people must be respectful and acknowledge each other’s roles. However, a young company should do everything, including making their own set.

S&N: How did you conceptualize a play like Words Have Been Uttered?

SS: One of the reasons why Tamaasha theatre was formed four years ago was essentially to do a very different kind of theatre. My own productions have started growing larger and larger, and that brings with it its own problems. For one, it starts getting expensive; you wake up in the middle of the night and ask yourself questions like “What am I doing? Am I taking risks in my work or am I playing it safe?”

You start worrying about these things. Also, the kind of relationship you share with the audience in a big theatre is very different; they’re there, you’re here, you don’t know who they are, they don’t know you. They sit in the dark and watch the play and go away. There’s no point when you cannot actually have any kind of direct engagement. That is also something I was missing a lot. So we decided to start the kind of theatre that only takes place in intimate spaces, with no more than thirty-five to fifty people in attendance; where the idea is critical, you don’t have to worry about scaling it down, et cetera. You really just concentrate on an idea which can be implemented anywhere, and where it is possible to have conversations with the audience before or after the play. With forty people it is very easy. For instance, after every show, we greet and tell them we will meet them in five minutes, after cleaning up and changing out of our costumes, and then we go and hang out with them. It is really nice when the audience members talk to you because they have questions, and you get to know what they’re thinking.

Hence, the experience becomes more than just “let us go watch a play”, you know. The audience also becomes an important part of the process in the event. In a sense, Words Have Been Uttered comes out of that kind of thinking about theatre. A lot of our work does reflect what is happening around us. I really believe that my theatre and my art have to do that. It comes out of the job of being who we are. It won’t help to change anything, but it helps us in understanding things a little better, a little differently, from a different perspective; conversations begin, and hopefully, that will lead to something. In the present time, there is no space for the minority’s view – majoritarianism is so strong that if I say something that counters what you are yelling out, then you’re not going to stop and listen to what I’m saying – you’re going to hit me on my head, you’re going to throw me into jail. The situation is very violent, very aggressive; there is no space for an alternate view. And historically it has always been the other view, the dissenting view, which has led to some movement ahead.

Many of the things that we accept today were not the popular view long ago. It is over time that people’s minds have changed. I mean, look at what is happening with the whole #MeToo movement, for instance: people are now thinking about it; in the movement for LGBTQ+ rights, people are now thinking about it. You can’t make those gay jokes anymore, you can’t, and you have to be respectful towards all communities, including the queer community, so much so that homosexuality has been decriminalized in India. Who would have imagined that it could be decriminalized in India? It has been a long battle but when it started, it started as dissenting voices. Given this, I believed we needed to look at dissent as an abstraction, and at how it has played a part universally. Galileo was a dissenting voice, and through him, modern astronomy came into being. In Syria, there are dissenting voices. In Palestine, there are dissenting voices, as there are in America, and so on. We tried to demonstrate how dissent has played its part across time and cultures. That was the driving idea behind Words Have Been Uttered. So we read a lot. Sapan, Irawati and my group gathered a lot of material. Then we started looking for themes, commonalities, and it is really like structuring an argument in theatre. You can see how an argument is being structured. Therefore, it is not just one play, or a singular narrative, or a narrative of events; it is a narrative of ideas.

S&N: When you are directing actors, do you believe in employing some technique, or do you encourage them to go with their instincts? In case of a conflict in the perception of an idea between you and the actor, what do you do?

SS: I remember when I was doing Sex, Morality and Censorship, I worked with two highly experienced actors, Nagesh and Gitanjali Kulkarni, and all I had to do was to say, “Listen, Nagesh and Gitanjali, this is the first moment of the scene, this is how you will be sitting,” and I would just sit back. They would just do the entire scene on their own; I would not have to do anything. Working with experienced and trained actors is like playing a beautiful instrument: you just have to put your fingers to it and the music starts. But with younger actors, it is almost physical, it’s like wrestling, so there are two extremes. I do not act and demonstrate what I want, I just construct a performance for them, which, perhaps, they would not have been able to do on their own, but in the process of it all, they understand how to construct a performance. At the same time, I am pretty clear on what I want. Some actors complain that I don’t give them space, but I just say “I know what I want”.

S&N: These days, a lot of young talent is entering the realm of theatre. What would you say to people who are taking it up as a career?

SS: The decision to be in theatre comes with having experienced a bit of theatre. It is very difficult to take a decision like that in abstraction. In fact, I would say, don’t do it; give yourself time, work with theatre for a bit and see whether you enjoy it. Because theatre has very peculiar demands and you really have to appreciate those. It is heroic to do theatre in today’s times: it is almost a calling; it is not a profession. And I say this because you have to be prepared to give up a lot of things that maybe your peers or contemporaries take for granted. I think there is huge pressure from the global consumerist culture that we live in, where success is measured by your ability to buy experiences, buy material goods, buy this, that and the other.

It is a completely warped system that we live in, and in a system like that, for theatre, you have to be ready to say “Okay I’m prepared to be earning one-tenth of what my peers are earning”. For three years I may not earn anything, I’m not going to have a car just like that, I can’t dream of a two-bedroom house. You are throwing away a lot of what is considered “normal” aspirations. That kind of idealism is required, and I think young people have that idealism. I am always extremely gratified that, every year, so many young people join the theatre. If they enter the theatre industry and they seem to be having a great time, which they all do, then I guess they’re getting something out of it. It may be different for everybody, but the youngsters are all getting something out of it. This is what the director I worked with and who trained me said: nothing goes to waste in theatre. You will always get something out of it. It is never the case that if you do theatre for a year you will say “Arey, I wasted a year”. That will never happen. The minute you open yourself up to do something purely because you like it and because it is important to you then it changes you. We are used to doing things only because we gain something out of it. I think it is important to do things just because they matter to you, and theatre falls in that category. I feel that is good for human beings generally. When you’re young, you’ve got to be idealistic, and if not when you’re young, then when else? If you’re not political when you’re young, then when will you be political?

S&N: Last, a look at the theatre scene today: at the moment, we have so many other kinds of media for entertainment. For instance, YouTube has risen to be a sort of industry, and there are also platforms like Netflix and Amazon Prime alongside other upcoming local ones, which means people have entertainment right at home. In such a world, do you think theatre still has its place, or do you think it is losing ground?

SS: Not at all. We still have people coming in large numbers to the theatre. Actually, it is difficult. There are many theatres running in different parts of the country. In some parts, it is flourishing; in others it is non-existent. That is an issue. Therefore, I won’t say that theatre all over India is in great shape, but there is a need to build a larger theatre-viewing habit among people; there is a great need for a theatre of quality and excellence to be produced all over the country, even in its remote pockets. And that means there is a lot of work to do, and this is not easy. Society has to decide that art is important and then these things will happen. Right now, people who make art do it by themselves, and it is made under very difficult circumstances.

I would say that as long as human beings are social animals – you might be wrapped up in your phone but at the end of the day, you still crave a little human contact, human company. I think the pleasure of watching something as a group, rather than individually, is very different. People really crave that sense of community. Second, I believe, a living, breathing human being on stage is a very powerful experience; you may see the most fantastic movie with the greatest special effects, but the kind of experience you get watching real-life people onstage is unique. I think people keep coming back for that, maybe they don’t come every day, but once in a while, they need that experience. I think that’s something we need to build on. That is why I say, let us not do theatre that you can see on television or in a movie; let us do the kind of theatre that you can’t see anywhere else. You’re not likely to see what you see on stage, on television. Thus, really, we need to consider that. In my opinion, this responsibility lies with theatre-artists more than with anybody else. How else could we use that magic of theatre? Why not do everything and die.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Sania Lekshmi and Nidhi Panicker.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.