The political self of beauty

South Korean artist Eunkyung Jeong’s interdisciplinary work at TAZ#2019 recalls the structure versus agency debate in social sciences—whether we are the product or disruptor of the society we grew up and live in. But by yoking elements and strategies not immediately associable with one another (such as a flashlight, a basement, drawings, and personal family stories) she affects agency in relation to one’s own place in cultural arrangements which frame one’s choices and opportunities. This results in a refreshing and empowering artistic contribution to the debate.

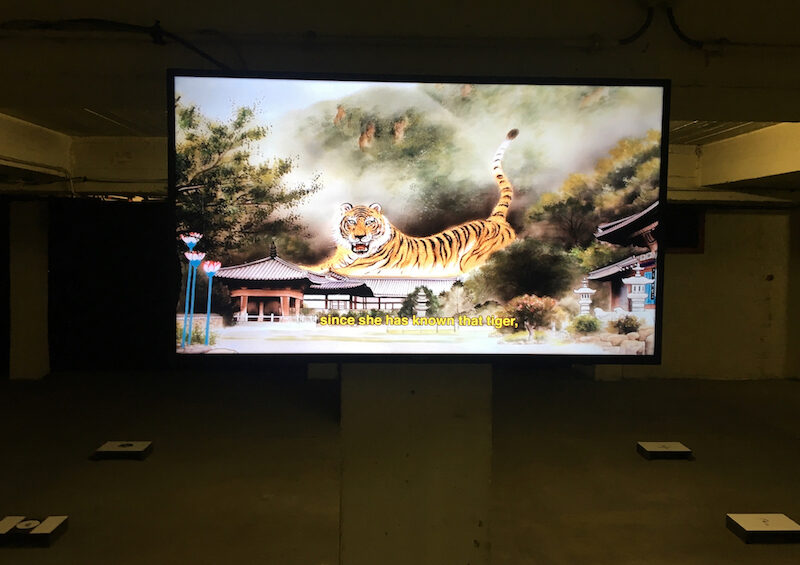

History is burdensome and, according to Jeong, it’s dark. At the opening and closing of this performative installation, the artist lets each viewer probe the dark terrain of the basement in a building – situated in a food district of Ostend – with a flashlight given at the entrance of the show. The introductory and concluding parts where the viewers are turned into performers themselves are mediated by a video presentation on two screens. This changes the meaning of the second performative participation at the end.

The interplay between light and darkness accrues an interesting meaning when the flashlight brings into visibility the exquisitely rendered drawings of different destinies of a beautiful stone. The viewers have no idea what this stone embedded in different surroundings is or represents. Without the presence of the artist (which some viewers, misunderstanding that this is a performance rather than an installation, do ask for) the ‘audience’ is given a performative role of literally shedding light on each of the variations of the stone and its environments. One by one, navigating from one station to another where these drawings are placed on the floor, the viewers-turned-performers bring into being a seriality whose meaning pivots on the notion of identity: being the same and different. (Both notions of agency and history and the exploration of the idea of ‘same and different’ also interestingly inform the lecture-performances of her partner Jaha Koo who also contributes to this project as the sound and music designer.)

The video that comes in between the performative acts of illuminating darkness charts the artist’s personal history of her mother and herself, in a traditional extended Korean family. By referring to both herself and her mother identically as ‘she’ and using ‘her’ as the possessive pronoun for both, Jeong delicately suggests the continuity and inescapability of women’s fate and their female subjectivity in the male-dominated Korean culture—a thread that runs through from her mother to Jeong’s generation. This is visible in the way the narrating artist, as a daughter, was named. As opposed to her brother whose name ‘Soo-ho’ (a brave tiger protecting or governing a country) suggests action and agency, the name ‘Eunkyung’ (shiny silver) she was given signifies how her family and society valorise her and her sex only in the realm of aesthetics: something beautiful to look at. The microcosm of this family history reveals a deep-seated sexual prejudice in a patriarchal culture where the male is equated with active politics and female the kind of aesthetics that is passive.

The alluring narrative, thanks to the selection of music and visuals that accompany it, deceptively promises a way out when her mother tries to ‘escape’ from the weary life of the housewife of a traditional Korean extended family by going to see a shaman. Ironically, the soothsayer further subjects her in another male-dominated narrative which adamantly reduces the role of woman as the mere supporter and reconfirms the role of men as the actor: ‘The Bong-Hwang [referring to Jeong’s mother] perch[es] on the tree [but] doesn’t spread its wings [as it is supposed to]’. The artist’s attention to the translative process inherent in the shaman’s narrative gives depth to this kind of all-too-familiar family anecdotes from Asia. Here, the symbolism of the mythical bird Bong-Hwang—which, in the East Asian culture, is king of all birds, hence symbol of high virtue—is intentionally appropriated to keep women in the role of supporters of male family members who take action and prosper in the world—a dichotomy of public and domestic life which also gets identified and challenged in the works of Western feminist writers such as Virginia Woolf. Although Self Life Drawing is culturally specific, this Korean experience is also identifiable to Westerners.

Amidst this locally-specific impasse where quiet ‘violence’ against women is engineered in the language and culture one speaks and embeds oneself in, Jeong interestingly turns to the Western logos and a particular way of thinking that comes with it. Unlike her mother, Jeong has the opportunity to live in the cultural imaginary ‘West’. Instead of going to a shaman, she finds salvation in linguistic activism: not only by imagining ‘what if’ her name draws on a more powerful and politically-engaged signified, but also drawing out and on the individualism underlying the Greek root of the word ‘autobiography’:

‘From the ancient Greek, autos means SELF,

Bios means LIFE and graphein means to WRITE or DRAW.

Auto-biography, a self-written account of the life of oneself.’

At this point, the viewers/performers dawn on the meaning of what they have seen with their flashlights—itself a metaphor for Enlightenment: the act of drawing as, not only a metaphor but a performative act of deciding for one’s own life. Here is the point where this deceptively simple work redefines our usual understanding of the role of aesthetics in life. Dextrously weaving personal narratives in ways that ponder and respond to questions pertaining to sexual politics, Jeong in this beautiful work transforms aesthetics from something passive into something that has a promising political potentiality.

This article was originally published on Etcetera on August 13, 2019. Reposted with permission. Read the original article here.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Rathsaran Sireekan.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.