Interview and translation by Kee-Yoon Nahm with contributions from Laura Gisondi.

Lee Kang-baek

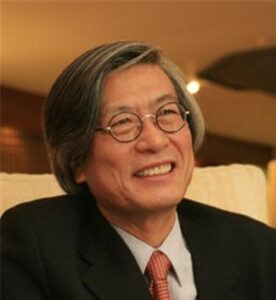

Lee Kang-baek is a celebrated Korean playwright who has been working consistently since his debut in 1971. He has written dozens of plays to date, published in eight volumes, and has won numerous awards in Korea, including the Seoul Theatre Festival Award for Drama, the Baeksang Arts Award for Drama, and the Daesan Literary Award for Drama. Some of his plays have been translated and published in English. Several of his best-known plays, including Five, Watchman, Wedding, Chaos and Order at a Gallery, and Spring Day, are collected in Allegory of Survival: The Theater of Kang-Baek Lee (2007), translated by Alyssa Kim and Hyung-jin Lee. A Feeling, Like Nirvana, translated by Alyssa Kim, is included in Modern Korean Drama: An Anthology (2011), edited by Richard Nichols.

Yellow Inn premiered in 2007 at the National Theatre Company of Korea. The play takes place in a run-down inn in the middle of a wasteland. When the play begins, the Owner and his Wife make a deal with the Sister-in-Law: they will hand over ownership of the inn if she can prevent at least one guest from getting killed. This is easier said than done, as it so happens that the guests have been fighting and killing one another every night for countless years. A cast of modern archetypes come to the inn, naturally separating into two groups. The older and richer guests—including the Retired Government Official, Lawyer, and Businessman—stay in the luxurious rooms upstairs, while the Salesman, Electrician, Plumber, and Student, are crammed downstairs in tiny rooms with no individual bathrooms. As the night wears on, tensions rise between the two camps—eventually erupting in bloodshed. The Sister-in-Law tries to calm the guests down, but the chasm that separates rich and poor, old and young runs deep.

I translated and adapted Yellow Inn for its English-language premiere at Illinois State University, directed by Myeongsik Jason Jang, September 25–29, 2019. As part of research for the translation and adaptation process, I met with Lee Kang-baek on July 29, 2019 in Seoul to talk about the play and his theatre career. In the interview, I discuss the changes that the director and I want to make to the play for the American production, including changes to some of the characters’ genders and the idea of using of Shakespeare’s King Lear as an intertext in the adaptation.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

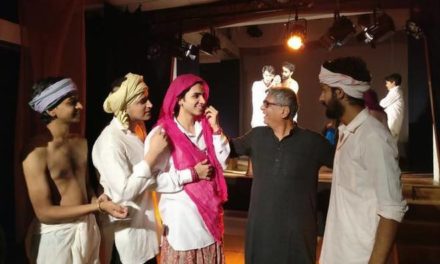

Yellow Inn, by Lee Kang-baek, directed by Koo Tae-hwan, Theatre Company Soo production (2016) Photo courtesy of Theatre Company Soo.

ON YELLOW INN

Kee-Yoon Nahm: Theatre critic Kim Mi-do used the term “comic grotesque” to describe your plays after 2000. What do you think about this term? How would you describe the style and aesthetics of Yellow Inn?

Lee Kang-baek: Oh Tae-seok, who was a fellow professor at the Seoul Institute of the Arts and Artistic Director of the National Theatre Company of Korea, agreed to direct Yellow Inn’s premiere in 2007. One day during rehearsals, he called me and said that he was struggling with the play. He wanted to hand the production over to a director who had more experience with my work. I told him that was impossible—rehearsals had begun and the production had already been promoted with him as the director. I said he had to do it. Oh is known for a distinctly Korean style and sense of humor. I’m not talking about traditional performance styles, such as madangguk. Anyway, he thought he could stage the play in his style, but it wasn’t working. I think the reason was because Yellow Inn’s language and sensibility are, in a sense, more Western than Korean. To be generous, you could say that the play is universal. On the other hand, you could also say that the play has no boundaries and can be vague. That made it hard to impose a particular color on the play.

So in the end, Oh decided to make the characters grotesque. I think this approach has its limits. For example, the Sister-in-Law comes across as being stubborn, yet tries everything she can to keep the guests from killing each other every day. She is the one ray of hope in the play. If you turn her into a grotesque figure, hope itself becomes a bizarre idea. The grotesque ends up creating more problems than it solves. Of course, the audience may be entertained. I’m curious why so many productions of this play are interested in grotesque humor. The 2016 revival by Theatre Company Soo played many of the scenes for laughs. Koo Tae-hwan, the director, had a brilliant idea when a murdered guest appears on the second floor covered in blood. The actor starts laughing uncontrollably. Later, when the other guests are killed, they don’t scream. They cackle and guffaw. I think younger audiences respond well to death scenes that are absurd rather than weighty.

The grotesque can mean many different things, but basically it’s about abnormality. It’s about purposefully twisting or inflating something so that it looks bizarre and extraordinary. But I wonder if that’s the only way to approach Yellow Inn. There is nothing normal about generational conflict, so I don’t feel the need to make the characters grotesque on top of that. Just this year, three universities asked for permission to do the play. But I have a feeling that these theatre students will treat my play like Ubu Roi. Ubu is so much fun. He swears and exposes the evil in human nature. But I am not interested in seeing these college productions—even though the students beg me to come—because I already know what they’re going to do. If a directing student contacts me and says they want to treat Yellow Inn like a Chekhov play, I might go see that. There must be something in the play that stimulates the grotesque imagination. But I don’t know what it is.

What immediately comes to my mind is the way in which violence manifests in the play. Violence has become a part of everyday life in this world. The first thing that we see is a stage full of dead bodies. When characters enter this setting, they don’t seem surprised at all. Death and violence have been normalized. I wonder if that aspect of the play evokes the grotesque.

The playwright has a responsibility to sort these things out before advancing the plot. In that regard, you could say that I’m irresponsible. Actually, it’s not just Yellow Inn. An actor should be able to take their first step into a play on solid ground. But most of my plays don’t have that. The actors feel like they’re stepping on air. That moment that you just mentioned, when the gravediggers come in and carry away the dead bodies—whether the gravediggers are insensitive to the corpses or shocked by them sets the tone of the play. I was irresponsible in that I wrote the scene without indicating what the gravediggers feel. But the actors can feel nothing, can they?

I don’t think that’s being irresponsible. You’re leaving open space for actors and the director to interpret the play.

You’re right. But why is it that every Yellow Inn production I’ve seen engages with the grotesque? Sometimes I wonder whether it’s because the Owner swears so much. I don’t think I’ve written so much profanity into a play before this. Since you’re translating and adapting the play, how about cutting out the curse words and turning the dialogue into poetry like Shakespeare?

Yellow Inn, by Lee Kang-baek, directed by Koo Tae-hwan, Theatre Company Soo production (2016) Photo courtesy of Theatre Company Soo.

Actually, I translated all the profanity into similarly crude words in English. I think the Owner benefits from the language. He is a straightforward character with no pretense about his greed; he curses to the guests and workers alike. But since you mentioned Shakespeare, one of the reasons that I used King Lear as a reference point in the translation and adaptation process is because of the Owner’s worldview. In King Lear, Lear’s two elder daughters flatter and pamper him to get what they want. But as the play progresses, they begin to express their greed and cruelty unfiltered. I think the same can be said about some of your characters. I imagined the world of Yellow Inn as a version of King Lear in which Goneril, Regan, and Edmund seize power after Lear’s death.

I think the death scenes later in the play are challenging, especially for students. You said that my play leaves open spaces for others to fill, but there is never enough time to rehearse. I think that the fundamental flaw of this play is the death scenes. I’ve tried to rewrite that part several times, but it still doesn’t work. I want more variety—for each death to mean something different. But the deaths all feel similar.

Maybe that’s because there are so many of them in quick succession towards the end of the play. Six people die in the span of a few pages.

That doesn’t mean that I want to rewrite the whole play. The director should think about how to make the deaths feel different—something that the playwright failed to do. It’s difficult because there aren’t that many distinct motives for killing someone. The murders are all based on hate, and hate is not a complex emotion. In fact, having different motives can end up getting in the way of the violence. What’s crucial about violence is that it’s rooted in an excessively simple emotion.

But there is the Student, who hangs himself rather than fight. His death is different from the others.

The student tries to flee but ends up coming back. Things are the same outside the inn. You could say that his death was forced on him. But from another viewpoint, he chose his own death. The other characters, meanwhile, are brimming with the desire to live. Yet they die. If I tried to make each death unique, the play would turn into a miniseries.

The distinction between the first- and second-floor guests represents generational conflict and class inequality. But I’m curious how the managers of the inn fit into that allegory. Do they belong to one of the two floors or do they comprise a different class altogether?

The Cook is not a part of the management. He’s an employee. At the same time, he makes money on the side by renting out kitchen knives to the guests. He talks about leaving, saying he doesn’t belong here. But he finds excuses to stay. In terms of space, I wrote in the stage directions that the Cook sleeps in the kitchen. The Owner, Wife, and Sister-in-Law come up from a trapdoor. Their room is not on the first or second floor. They live underground where it’s safe.

Maybe because the management lives in the basement, I thought a lot about Yellow Inn when I saw Bong Joon-ho’s film Parasite (2019), which recently won the Palme d’Or at Cannes. When the Owner first appears onstage by sticking his head out of the trap door, the image can be pest-like.

I haven’t seen the film. But a lot of my former students called me after seeing Parasite and told me that it resembles Yellow Inn.

So I wasn’t the only one to think that. The film’s title evokes a marginalized class that doesn’t fit into the traditional categories of bourgeoisie and proletariat. Instead, these human parasites survive by leeching off of an unjust social system. There is the term “underground economy”: a system that exists out of plain sight. I feel that the Owner and Wife thrive in a system like that.

I think the film and my play live in a similar imaginative space. But going back to your question, the managers of the inn stay out of sight when danger is imminent. They don’t intervene. There are always people who sustain and manage conflict in order to benefit from it. They might criticize social problems, but they don’t want them to go away. To be honest, I didn’t want the Owner and Wife to come off only as greedy characters. As characters who have a hand in the cycle of violence, I wanted their selfishness to reflect more than base desire.

I find it interesting that when the Owner makes the deal with the Sister-in-Law, he’s actually confident that she will fail. He is someone with a crystal-clear understanding of how the world works.

But why is it that the Sister-in-Law believes that she can save someone? Is it because there might be a day when the yellow dust stops blowing? I guess the play wouldn’t work unless she tries.

Right, unless there is hope. What do you want audiences to take away from the play?

If I were to critique my own play, I would ask, “Don’t we already know all this?” If you are even a little aware of a generational conflict or have experienced it yourself, you already know what this play is trying to say. An audience member might think: ‘Does the playwright think we’re dumb? I’ve experienced this kind of division in my life far more explicitly than the playwright is showing.’ I’m curious myself what audiences take away. In a sense, later productions are at a disadvantage compared to the premiere because the generational gap has been discussed to death. It’s a cliché at this point.

But in the United States, even if audiences are familiar with the idea, the way that you turn it into a story can feel different and refreshing. Personally, I’m duped into having hope every time I read the play. I keep wishing that maybe the Sister-in-Law can succeed this time. All it takes is for one guest to understand what she is trying to do. That’s all it takes for that person to live. Even though it doesn’t pan out, that sense of hope keeps me engaged.

I’m glad to hear that. I guess that’s why you translated the play.

To read Part 2 of this interview, click here.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Kee-Yoon Nahm.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.