In this interview, Rabih Mroué talks about micro-narratives, the ability of theatre to enact a compression of time while mediating a certain kind of immediacy not found in film or video works (though Mroué does make a case at one point). The discussion expands into the role of the audience, the existence of many audiences, and the fact that every individual will perceive of what they see differently. Mroué underscores the importance of time in this context. That his work is about considering world events from multi-point perspectives, Mroué acknowledges the difference in his approach and the space theatre affords him when compared to the way world events are broadcasted in the main stream media.

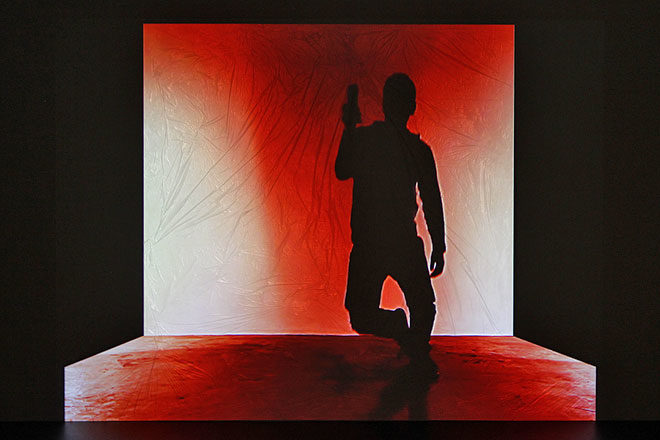

Rabih Mroué, Riding on a Cloud, 2014. Performance with Yasser Mroué. Photo creds the artist and Sfeir-Semler Gallery, Hamburg and Beirut

Göksu Kunak: In 2009, I saw your lecture performance – or in your own words ‘non-academic lecture’ – The Inhabitants of Images in Istanbul. Through a selection of photographic images of deceased figures such as a poster of Gamal Abdel Nasser and Rafik Hariri standing together in a garden, you analyzed the capacity images have to manipulate our feelings when it comes to our personal and collective memories. In Turkey, history is being rewritten by the demolishing of buildings and squares – even Emek Sineması, where I watched The Inhabitants of Images, was demolished to build a shopping mall. In this erasure, memories are lost. As far as I know the same situation is happening in Beirut, too. What do you think about methods of erasing or re(writing) a (hi)story: the tendency to pretend as if things never happened or, on the contrary, assuming they did?

Rabih Mroué: It is a broad subject but I’ll try to tell you my opinion in a simple way. When I think about memory, whether it is personal or collective and whether it is written in a history book or preserved in an archive, I perceive it as a very violent act because of always being selective. The selection of certain events and the eliminating of others could be done intentionally or unintentionally, could be for ideological or political purposes and could be for personal, psychological, or sociological reasons and so on. Although some people try to, remembering every instant is impossible. When we recall a certain event, images and moments come back into our minds and when we try to narrate them we try to fill the gaps in-between. In that way, the fiction starts to interfere and becomes part of our narrative – even unconsciously. If there were three people on the same spot, who have all witnessed the same event and each were to tell you what really happened, each one of them would tell it differently because each one would relate to it differently. This is also how historians work – they focus on certain events and desert others and therefore a selection occurs. The question is how to decide what is important and what is not? Do we have the right to choose? My answer would be yes; people, whether they are historians or not, all have the right to do so but we should be aware that this choice would only be his or her version – their personal point of view. No one could be merely objective.

Someone should choose and decide in a collective manner on what we should remember and what should we forget. It is always a power relation between the different authorities and a violent struggle between remembering and forgetting. As an example, when you are with your parents you can’t tell them everything you remember. You would hide little details or incidents and they would do the same as well. And in some situations parents might get angry or sad because their son or daughter still remembers an unpleasant incident. In this sense memories are uncontrollable and bring surprises – most of the time they come brutally.

In my work I always try to avoid accusations. For example, you described the manipulation of images in The Inhabitant of Images and this was not my point at all. Because, for me, it is very easy to say that these images are a photomontage – end of discussion. In this non-academic lecture, I proposed to go beyond the fact that they are photomontages and believe that they are true. The person behind this image wants us to believe that it is not a fabricated one. Actually, it is made in order to transmit a message or an idea.

This is why I proposed to believe the image and try to analyze the socio-economical and political discourse behind it. For me, the interesting point is not to reveal the fakeness or to make accusations but rather to make the effort to read what is between and under the lines. In this sense what is being hidden gains significance. The main point is not to legitimize this point of view but to accept it as one among many other different ones. In this manner there should be many versions of the same event as well as several history books. By analyzing the differences one can understand the political and social discourse they are implying. It makes one realize that history is not fixed but is a continuous conflict. One should try to collect as much as possible to broaden their perspective and comprehend history from various angles.

GK: Bergson claims that, “The pure present is an ungraspable advance of the past devouring the future. In truth all sensation is already memory.” How do you perceive the past, present, and future?

RM: I totally agree. For me, the present is something that one can never grasp. It slips from our hands. When I say ‘now,’ this ‘now’ has instantly become part of the past; the moment I utter it, it’s already dead. Actually, the only way to talk about the present is through representation. That’s why live performances (theatre, dance, music and so on) are different from films and videos. It is always said that in theatre the action is happening here and now, indicating that it belongs to the present time and it can never happen again in the same way. Of course one can argue with this. But in any case, what does here mean, especially today with new technologies, when we can be here and there at the same time?

33 rpm and a few seconds (2012) is a theatre show without actors that I produced in collaboration with Lina Saneh, in which the machines are the main protagonists. Eventually the machines perform exactly the same way in every show so there were no differences in their rhythm or energy. However, we felt that both the rhythm and the energy were not the same because of the different reactions from the audience. So the audience affects any performance, even when the performers are steady.

One can apply the same logic to movies in relation to spectators. It is recorded but if one watches the same film two times the reaction would not be alike. Experience differs. One can argue that in a film there is the possibility of reshooting if an actress or actor forgets their lines, whereas in theatre no such thing exists. But what if there is a power cut whilst watching a movie, which is something very ordinary in Beirut, or if someone stands up in the middle of the film and blocks the view. There is an interruption similar to the moments when an actor forgets some of his lines in a theatre performance. My argument is that even in a recorded projection accidental things might happen and each screening would be a considered a unique performance.

Going back to your question about how to perceive the past, present, and future, I believe it is by focusing on the present in theatre; we try to talk about the past and try to think of the future. The present is where we try to represent the past and the future. Theatre is interesting in those terms: it is all about representation.

GK: Don’t you think this play with the notion of real and the presence of the moment in performativity and in theatre is reminiscent of a puzzle? There is a concentration on a micro-narration by taking performance out of its context somehow as you did in the Pixelated Revolution (2012), in which you performed a narrative of the Syrian Revolution with images culled from the Internet and videos posted by civilians attempting to document the latest acts of violence. I wonder if what is represented on the stage is real or not – after performing, it turns into a new reality. Do you agree?

RM: Of course it is another reality, another reading, another interpretation. Like life, people pretend they are neutral. It means nothing; nobody is neutral. The time elapses. Human beings imagine the future and the past as well. Whilst remembering we start to invent the past. Within this context the past is also ungraspable – not only the present.

GK: Riding on a Cloud (2014) springs to my mind: the theatre piece you based on your brother Yasser’s experiences in the aftermath of the Lebanese Civil War, which combines pre-recorded video and live spoken word performed by Yasser himself. Yasser has to record his memories in order to seize the moment – a result of an unfortunate event from the days of Civil War. The recorded image functions as his own reality – Yasser encounters reality through the eye of the camera.

RM: It is a hope to grasp and freeze a moment from the past; this is what photography promises us. In fact a photo makes you think that you know the moment although each time something is changing – you would add or subtract certain things from your story. The information, how you narrate it to others and to yourself would never be the same. Try it. Precision is not possible unless you write it as a text and then performed it each time you talked about it. Then it would become a performance.

GK: The juxtaposition of voices, narration, and sounds are vigorous aspects of your works – as in Biokraphia (2002) with your partner Lina Saneh or Riding on a Cloud. You use texts and letters; sometimes you create a theatre piece or just a lecture performance as a ‘device.’ In the process of creating how do you know which medium will be the best to narrate a certain scenario or tale?

RM: I have no methodology to follow. Actually, if I come to a frame or a style I immediately attempt to deconstruct it. At the same time I don’t restrict myself. If I do make restrictions it is to free myself from other limitations that I cannot get rid of. Not using dialogues or not having eye contact between the performers on stage are two examples. This method functions so as to free me from other obstacles or stereotypes. I guess Dogme 95, a movement of Danish filmmakers including Lars von Trier and Thomas Vinterberg, were aiming for this. The dogmatic rules they put in place are designed to free themselves from the film industry and its restrictions. It is dangerous though: you may fall into your own dogmatic thinking and become imprisoned by its rules.

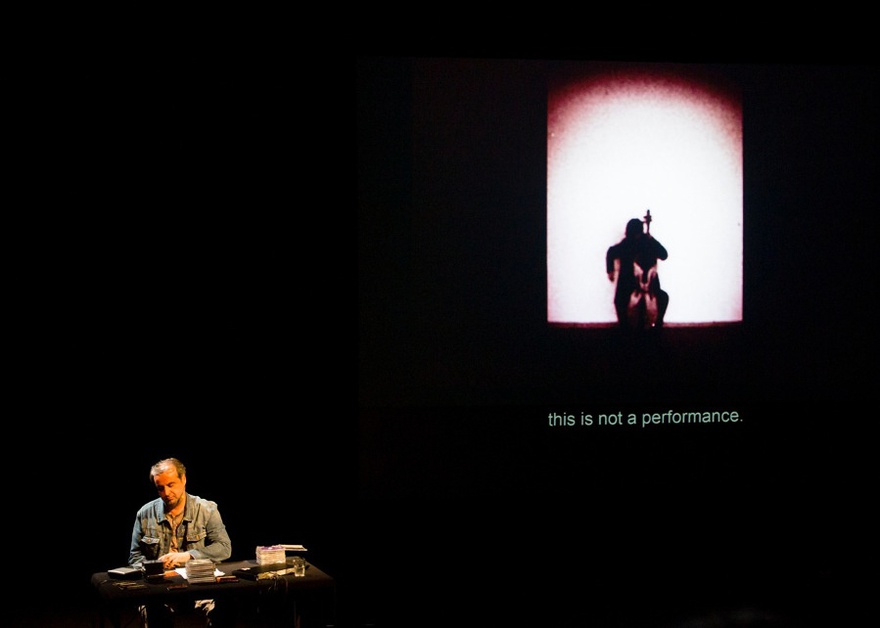

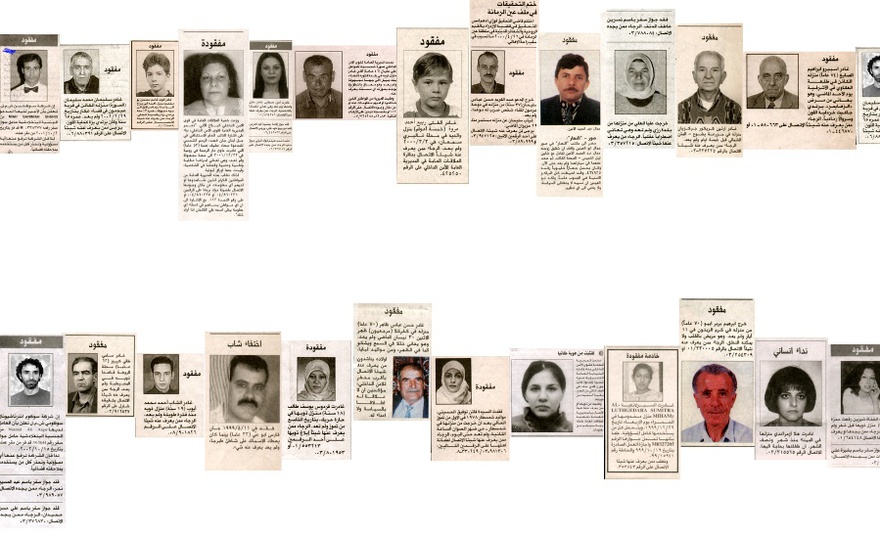

In some performances with Lina Saneh we have started to realize that we are confronting theatre with other mediums. In Photo-Romance (2009) we tried to separate the film’s elements and put some of them on stage. Instead of watching the movement of the pictures we decided to make it with still-photos like a roman-photo or a story board: the music is trying to follow the still images, while all the dialogues were added by Saneh ‘live’ on stage. In Looking for a Missing Employee (2007) newspapers were brought into the theatre, which reflected the temporality of the performance. In this performance I followed the case of a missing employee through the newspaper articles. The news came in, day after day, non-stop for 16 days until it suddenly stopped; nothing was written about it. A question came up at once: how could you represent these 16 days in theatre? I suggested to the audience that they listen to three minutes of music and try to imagine as if these three minutes represented 16 days. I remember that some friends told me to shorten this music because they had the feeling it was too long and boring. For me, it is just to highlight differences of temporality and how theatre condenses time – compressing three months into two hours, for example. It was also about the fact that even on stage a minute without doing anything can be felt as too long.

So these would be some examples. As I have said, I try not to frame myself in a certain style. I place importance on liberating myself in my own work. No recipes and no ready-made formulas.

GK: Contemplating this shift with new media, what do you think of Guy Debord’s criticism of the ‘spectacle?’ Recently that spectacle transformed into the hope for a possible revolution; how might you explain this transformation from spectacle to ‘pixelated revolution(s)?’

RM: I can’t pretend that I can argue with Debord since I don’t know his writing very well. But let me answer your question from my own experience. In every era there are technologies that emerge, first starting with the authorities as a tool to control. Over time people learn to use these tools against authority. In the same manner, although the Internet is still being used to gather information about people all around the world whether the purposes are commercial or political, there are always cracks allowing people to slip through and work within them against the authorities. This is what happened in Egypt, Tunisia, and Syria. Nevertheless, is there a possibility of making a revolution just with these tools through just Facebook or Twitter? I doubt it. These tools can only facilitate the communication between people.

Let’s take another example: in the 1970s it was the audiotape that played the same role in the Iranian revolution. The cassette engaged people and ignited the movement. While he was in exile, all the speeches of Khomeini were recorded on audiotapes and sent to Iran. Activists were copying these tapes and distributing them among the people. Later, Twitter became the main device for the Iranians in 2009 who were being suppressed by Khomeini’s Islamic regime, to create a protest movement in the country.

Consequently, power tries to find those cracks, modify them and correct the system in order to exert full control through it next time. But I assume people will always find their own ways to appropriate any system and use it against power.

Rabih Mroué, Looking for a Missing Employee, 2003. Photo creds Ashkal Alwan and Sfeir-Semler Gallery, Hamburg and Beirut.

GK: In your works, you address political concerns through micro-narration. The short story examined in detail contains more. How did you find this language?

RM: I don’t know. I can say that, in a way, some artists fall into this error of generalization. By generalizing one starts to talk about big titles like ‘The War,’ ‘Love,’ ‘Sacrifice!’ I find this very dangerous because it makes art a-political. What I’ve learned from my experience is that a topic should be very specific and specialized. In this sense, that war can’t resemble this one and the experience during this war is different, your body movement is different, your feeling, your thoughts, the reasons, and background – everything is different. What I found out is that the more you are precise about your subject the more you connect with your audience. From the very personal and defined, I assume that the audience will understand that every story has its own complexity and differences and that it needs an effort to be understood. Nevertheless, it pushes each one of the audience members to formulate their opinion and their own set of questions. For me, I am always aware of not giving any conclusions; I prefer to ask questions. I don’t try to simplify or explain because the moment I do this I start to compromise.

GK: Your approach towards multiple possibilities and perspectives within a certain moment recalls the concept of speculative realism: the idea of potentiality in a world where objects beyond our perception declare that we, as human beings, are not the center of the encounters around us, which opposes the widely accepted thoughts of Kant. What do you think of the way a human being discerns his/her surroundings?

RM: Let’s talk about the beheadings that keep occurring today. It is happening in a region but we don’t know the exact location. The executor has no face, only a mask covering it. Actually, the only way to know that this act has taken place is through the Internet. Uploading the videos of beheadings on the Internet is their way of announcing their dreadful deeds. They want to spread their statements through this medium. If the videos were not uploaded then it would be as if the crime did not take place because we are unable to know about it at all. So it is as if it never happened.

I assume these crimes are filmed and uploaded on the Internet for one purpose: so that we can watch them. In a way the Internet is playing the role of the public space in the Middle Ages, where people gathered in the public square to watch the verdict of the king who has control over the guillotine. Because of that, one of the ways for us to fight against these crimes today is actually by refusing to watch the videos. Every time you watch one of these videos the decapitation happens again and again – as my friend Bilal Khbeiz wrote. The more people who watch the video the more the executors succeed. Paradoxically, there are many other things that are happening around us but we are not aware of them. When you don’t know about a certain incident it is as if it doesn’t exist. This philosophy can be applied to the ‘Other’ – if you don’t want to see the ‘Other’ then it will be as if this ‘Other’ does not exist. But even if you don’t recognize it, they do exist! At some point they grow and suddenly appear in front of your eyes. Then you are surprised.

So there is this tension – something is there even though you can’t see it. The media is really powerful nowadays. I feel that if you are not seen in the media you do not exist. Recently, and for the first time, awareness of the war against Gaza was widely spread around the world through the media. Despite all the technologies, and thanks to the same technologies, it was impossible to hide this crime. People were able to witness what was going on without any borders. Since 1948 Israel has been committing crimes and massacres but because there was little coverage people did not really know what was going on there. This is exactly the same as what is happening with ISIS. People are asking: ‘Where did they come from?’ In reality they were always here, within us but in a latent state. We need to open our eyes and if we do we have to learn again how to look and see because with all the images today we are no longer able to understand what we are seeing! Actually, I agree both with Kant and the Speculative Realists – yes, something doesn’t exist without me seeing it but it also exists even though I don’t perceive it.

GK: In an interview discussing your works, Monique Bellan said: “When I saw [the play] in Germany, this was not an issue at all, but […] when Mroué performed Three Posters (2000) [which addresses the self-conscious visual aesthetic of martyrdom videos among Lebanon’s secular militants], the German audience thought a figure in the poster hanging behind the actor was a Hezbollah fighter. Actually it was a photo of his grandfather, a Communist intellectual.” Your performances are strongly bound to the history of Lebanon, however there are universal stories concerning several values that one can grasp. Do you think that different cultures observe a performance in different manners?

RM: I have a problem with what Monique Bellan wrote, mainly when she says the ‘German audience thought…’ as if the German audience is one person or one entity and she, for some reason, does not belong to this audience, maybe because she knows the Lebanese socio-political context very well unlike a ‘foreign audience.’ The German audience, just as with the Lebanese audience or any audience in any city, consists of individuals and each has their own thoughts. Sometimes these thoughts are similar and sometimes they are not. Two spectators who have never met and have lived in different cities, who both watch the same performance but on a different day and in a different city could share the same ideas. As far as I know there was one journalist who wrote that what was hung behind me in Three Posters was the photo of the Iranian religious leader Khomeini, while in reality it was a photo of Hassan Hamdan − the Lebanese Marxist philosopher who was assassinated by fundamentalists supported by that very Iranian leader. I believe that the journalist made this confusion in the interest of making his article more exciting. It was very clear that we were talking about the Lebanese Communist Party and about suicide operations carried out by secular people belonging to the national resistance against the Israeli occupation in Lebanon. Not to forget that the year of the performance was 2001, before the attack of September 2001, and it was presented in Germany in 2002 right after the attacks. Therefore, maybe, the journalist wanted to link it directly to the Islamic fundamentalists and the terror of Islam. And honestly I would think this could have been happened in any city in the world, either in Beirut or in New York: it is not because it was in Germany or that the audience was German.

Cultural identities are not fixed or rigid, they are constantly changing and evolving according to many factors; from technological inventions, new laws, and socio-political changes to new theories in science and so on. In this sense I can find similarities, connections, and common ground between individuals who live in any city of the world, just like I can find contradictions and tensions between individuals living and belonging to the same city.

The question is always how to address the audience as individuals and not as a mass of people and how to build a performance or theatre piece that opens other possibilities: a work that creates a constructive debate and a dialogue between individuals. Of course it is about confusions, misunderstandings, different interpretations, and opinions. It is about doubts and questions. It seems to me that the journalist I mentioned above was actually doing the opposite by simplifying things and taking them for granted. I assume that this is the problem with journalists who cover daily events. They are under pressure to produce and write quickly in order to get the latest scoop. There is no time to really investigate or to think deeply and to go into the complexity of the work or the event. This is why most of the time their reviews stay on the surface, simplified into binaries, easy to read and ready to be consumed, full of mistakes. Luckily there are some exceptions. For me, I would like to be careful with the topics I am dealing with and to slow things down. In other words, I insist on taking my time to think and think and think. This should be everyone’s right.

Theater with Dirty Feet. Rabih Mroué Photo creds Haupt & Binder

Rabih Mroué is an actor, director, playwright, and a The Drama Review (TDR) Contributing Editor. In 1990 he began putting on his own plays, performances, and videos. Continuously searching for new and contemporary relations among all the different elements and languages of the theatre art forms, Mroué questions the definitions of theatre and the relationship between space and form of the performance and, consequently, questions how the performer relates with the audience. His works deal with the issues that have been swept under the table in the current political climate of Lebanon. He draws much-needed attention to the broader political and economic contexts by means of a semi-documentary theatre.

This article was first published on www.ibraaz.org. Reposted with permission of the publisher. Read the original interview.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Göksu Kunak.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.