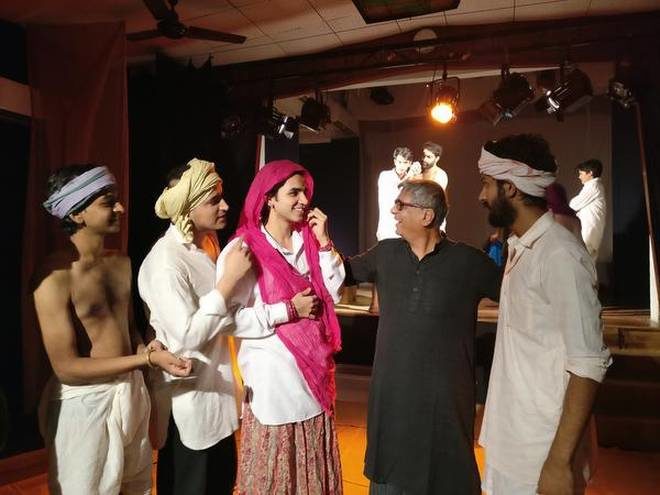

Mahesh Dattani explores the symbolism, futurism and surreal influences of Spanish dramatist Federico García Lorca by directing a Hindi adaption of Yerma.

The Drama School Mumbai’s annual production, which showcases their current batch of 14 students, is a take on Federico García Lorca’s Yerma, rechristened Maati in this Hindi adaptation by Neha Sharma, directed by noted playwright Mahesh Dattani. In conversation with The Hindu, Dattani talks about the queer themes that he has explored in the play.

Why did you select Yerma?

Jehan (Maneckshaw) had suggested we do a classic this time. He was keen to do Karnad’s Taledanda, but I was really struck by Yerma. I had caught Ebrahim Alkazi’s production of Lorca’s The House Of Bernarda Alba. There have been too many productions of that already. With Yerma, there is such a queerness to the play. The characters are predominantly female, and we had 11 male students. I thought it would be great to see how we could explore fecundity and barrenness through the male body. That’s not such a radical interpretation if you dig deeper into the text. There are many instances when Maati (the play’s protagonist) likens herself to a man.

Is this inherent queerness, in the hands of a testosterone-charged ensemble, subverted or amplified?

I was amazed at the sensitivity with which the men handled their parts. They consciously avoided stereotypes. The first thing we did was to discover the language of gender.

It was simple really; it was determined by the clothes they wore. That’s why I set the play in Haryana because the concept of femininity there is completely different, there is a certain robustness to it. I haven’t really focused so much on cross-gender portrayal as much as discovering the rhythm and flow of a character—how much of it is constructed as gender and how much of it is just character.

So the men play women, and vice versa in the play?

No, I have women playing women as well. I cast the actors on the basis of their energies. For Maati, I have three identities—one male, one female, and the third is transgender. The male identity is almost androphobic. In the play, Maati often invokes a loathing for men. Getting her male alter-ego to express this, because it is the maleness in her that is seeking freedom from patriarchy, made sense to me. Even in queer culture, there is a bonding with the feminine that is far deeper than the sexual attraction to men. That was what I wanted to explore. Also, the desire of the trans-person is that she wants a womb but ultimately comes to term with her barrenness.

How do you safeguard your female actors—sometimes in cross-gender pieces, the women become peripheral even in a play about femininity.

This is where I trust the text. The feminine energy is already so strong that the gender of the actor doesn’t matter. Organically, I feel I have used them the right way because it didn’t even occur to me to safeguard them in any way. The principal Maati is a female actor (Tanvi Lehr Sonigra). Shruti Achesh and Lauren Robinson alternately (there are two casts) play this lascivious older woman who has given birth to 14 children—her procreative vigor being the very antithesis of Maati. So, in foregrounding queerness we are in no way othering the woman because the woman remains at the center. In fact, there is a hilarious scene in which the women play women, in which I’ve asked them to play up the stereotypes as if they were men playing women.

How do you delineate trans in a space in which cross-dressing is already part of the turf?

The trans-Maati was informed by the text. The minute you focus on this so-called delineation you are using the language of gender. For me, I wanted to view this by removing the language of gender. If the language of gender is silent then what do you do? Obviously, the actors bring their own gender energies, which is almost a given. But the more you attempt to delineate the more politically incorrect it becomes.

What were the challenges you faced working with students?

It helped me rather. I don’t think I could’ve done Yerma with a regular bunch of actors, who are so short on time. The level of involvement I get from the students right from the dramaturgy to the research and the meta-text is invaluable. For instance, Hari Om (Meena), who is from Haryana, went home and brought back footage from rural life there, of how women work in the fields, and how men dance like women at times. So I wouldn’t have it otherwise.

Maati will be performed at the Drama School Mumbai, Girgaon on March 9 at 7 p.m.; free entry, with seating allotted on a first-come-first-served basis.

This article originally appeared in The Hindu on March 7, 2018, and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Vikram Phukan.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.