The Talmud, Meta-Phys Ed.’s new play at The DOXSEE Theater in Brooklyn, is ambitious. I mean, just look at that title. Talk about chutzpah. The one-act play, directed by Jesse Freedman, proudly advertises its source material: “Based on the Talmud and Kung-Fu films,” read all the promotional materials. I went to the theater expecting both entertainment and education. I was deeply disappointed.

Four performers appear in the show – Lucie Allouche, Abrielle Kuo, Eli M. Schoenfeld, and Jae Woo – wearing identical Tiffany blue turtlenecks, loosely belted trousers, black slippers and a succession of flowy robes. They are accompanied onstage by Lu Liu, virtuosic player of the wooden stringed instrument the pipa. Electronic music, sound effects, and a brief guitar riff are provided by Eamon Goodman, the very talented sound designer who I think went to the same college as me, a liberal arts school where radical Jews are incubated.

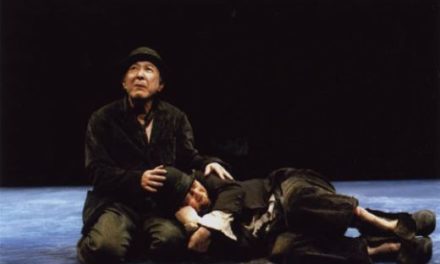

Photo by Jenny Sharp

The dialogue comes directly from the Talmud, the central text of scholarly Rabbinic literature. Here’s a little refresher if you’ve lapsed since studying for your bat mitzvah. The Torah is the five books of Moses, AKA the Hebrew Bible, AKA the Old Testament. The Talmud is a commentary on the Torah. It documents rabbis’ debates over interpretations of law and language. It’s composed of two parts: the Mishnah, which compiles the debates, and the Gemara, which debates the compilation. We are a chatty people.

All of this is to say, the Talmud stands for scholarly analysis and intellectual rigor. Just like modern legal writing, it’s not particularly riveting material. Judaism is a legalistic religion, and while the judicial protocols are amazingly sophisticated, there’s not a lot of drama there. If you want excitement, read the Torah. Seriously. The play The Talmud doesn’t shy away from this, creating long sequences out of land disputes that occur after the end of a war, for example. More engaging, of course, are the bits with actual narrative: like the story of how one rich guy’s bruised ego ultimately led to the destruction of the Temple and a three-year siege of Jerusalem.

With a run-time of only 75 minutes, the play moves fast, and not for a lack of verbiage. The performers all delivered their lines with stunning speed, as fast as than my zaide used to recite the blessings before the meal and with the same result: you can’t keep up. On the one hand, this creates a comprehension problem, with long names, archaic terms, and the occasional Hebrew word flying at you. But on the other hand, there’s a problem of intention. I quickly understood that The Talmud is not an emotional play, it’s an intellectual one. But with the actors zooming through the text, what’s missing is the act of thinking. Supposedly, they’re representing rabbinical debates, yet they play it like they’re rattling off sports stats.

Photo by Jenny Sharp

There are no characters to speak of, at least, not for long; the performers occasionally inhabit the roles of figures from these episodes. But their challenge is different. Adding dynamism to what could be a static script, they move dancerly across the stage in choreography drawn from kung-fu, ancient Chinese martial arts. Some of it looks like highly stylized stage fighting, except that they never make contact. Most of it is acrobatic. The issue is, it never became clear what the kung-fu choreography brought to the Talmudic text, or vice versa. Both are traditions based on long study, deep concentration and respect for ritual, and it’s always encouraging to find synchronicities in seemingly disparate cultural practices. But fusion, whether on stage or in the kitchen, only works when the finished product is more than the sum of its parts. A play “based on The Talmud and Kung-Fu films” ends up like a kimchee quesadilla: good enough for one night but still not challenging my notions of what kimchee and quesadillas can be.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Abigail Weil.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.