Fresh from a sold-out run at the Edinburgh International Festival, Tim Crouch’s latest piece (a co-production between the National Theatre of Scotland, the Royal Court, Teatro de Bairro Alto Lisbon, and the Attenborough Centre for the Creative Arts) is currently on the London leg of its international tour. As with most of Crouch’s work, the main appeal here is the invitation to the audience to take on an experimental role in the theatre-viewing experience. In this case, specifically, we will be reading – as in: actually turning the pages of a book – together. The fictional universe in which this sort of audience engagement makes most sense is one of a religious congregation – so this is the sort of context we’ll find ourselves co-opted into. But, once again, in the usual Tim Crouch way, there is a story at the heart of the experience.

Briefly, the piece concerns a family stricken by grief. Some fifteen years before the play’s action begins, a little boy, Felix, drowns in a frozen lake despite his father Miles’s selfless attempt to save him. Mother Anna and sister Bonnie have witnessed the tragedy and, years later, when Miles awakens from a coma which he fell into following the incident, they embark on a spiritual adventure to Peru prompted by Miles’s coma-induced visions. The truly inventive aspect of this theatre project is that all the backstory is made available to us through Rachana Jadhav’s black-and-white drawings, in the form of a graphic novel whose pages we examine together at the outset of the performance, guided at every turn by one of the performers.

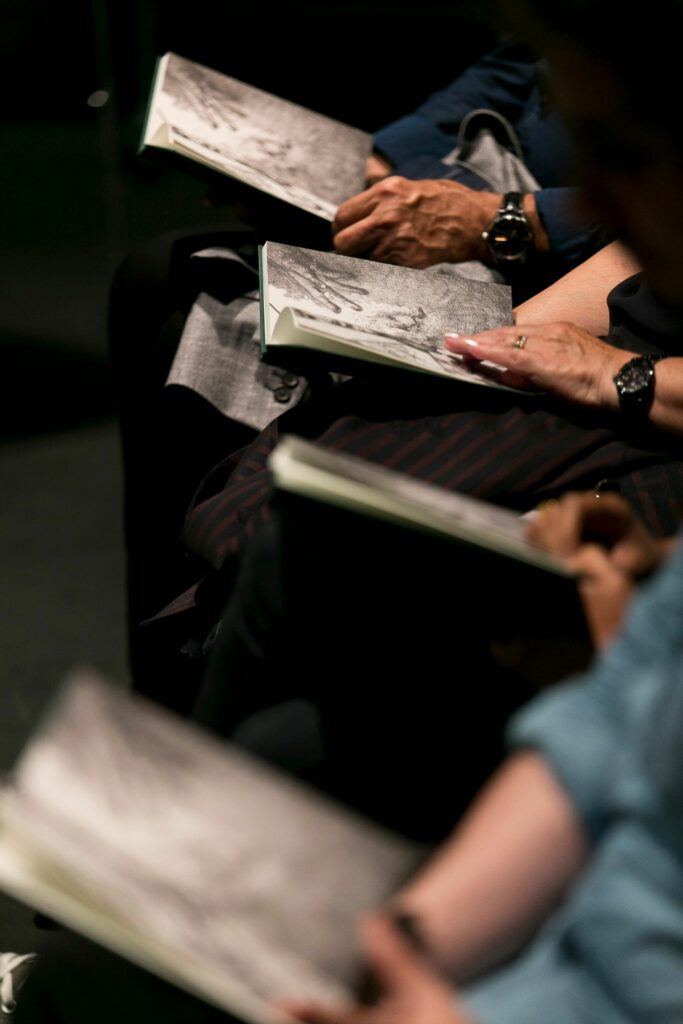

As the action of the play begins, we enter a conversation between estranged mother and daughter, Anna and Sol (a girl we gradually recognise as brainwashed Bonnie). Both we and the performers are holding the same hardback version of the script, bound in dark green. We simultaneously follow the words on the page and their being read aloud, all the way to the end. And ‘the end’ is foregrounded from the start as ominously final too, keeping the suspense rising, making a veritable page-turner out of this unusual show.

2) Total Immediate Collective Imminent Terrestrial Salvation . Audience members holding book. Illustrations by Rachana Jadhav). Photo by Eoin Carey.

Those familiar with Crouch’s work will experience the piece as part of a natural succession in his formal experimentation series that began with My Arm in 2003, followed by An Oak Tree (2005), ENGLAND (2007), The Author (2009) and Adler and Gibb (2014). As Crouch has often explained in interviews, one of the definitive features of his performance-making is an interest in actively using the audience’s imagination as part of the live performance encounter. My Arm is about a protagonist who has spent a considerable part of his life keeping an arm raised above his head, and although Crouch never uses any such illustrative physical gesture in his performance of the script, the audience have a lasting memory of it based on what they had clearly imagined. Taking this simple convention further, Crouch has replaced human characters in performance with inanimate objects in My Arm; he has written An Oak Tree on the basis of the audience being able to actively substitute one thing for another, and challenged the idea of a character having to be played by the same actor every night. Ultimately, in ENGLAND, he has two different performers of different genders playing the main protagonist simultaneously, and at one point the entire audience is cast and addressed as a single non-speaking character. At the core of Crouch’s oeuvre is the idea that the relationship between text and performance does not have to be a literal one (in the way that realism has led us to believe, perhaps). Accompanying this is a potentially democratising function that his brand of participatory dramaturgy affords to his actively imaginating audience.

In his latest piece, the author is, by his own somewhat provocative admission, exploring a kind of dictatorial leadership that playwrights as creators of fictions model. ‘For the duration of their play, the audience submits to [the playwright’s] manifesto’, explains the preface to Crouch’s published script. This idea of god-like creation is manifest in the piece’s form where we are confronting head-on the dialectic tension between the words and their meaning. As is often the case with the Bible, or any scriptures in fact, we face the problem of interpretation – do we follow the spirit or the word of the text? And if the former, what level of interpretation is allowed? Crouch makes this complex because, contrary to most theatrical performance, he places the focus on the words in their literal form here. He deliberately suspends the process of interpretation for as long as possible, for the audience to carry out in their own time, on their way home; but until then, they too are part of the world he has created.

Nevertheless, the piece makes space for playfulness too: moments of irony, moments of benevolent acknowledgement of our dual presence as, on the one hand, our curious, impatient, fallible selves, and on the other, the role and the rules we are assigned. There are also lines that are spoken by the performers seemingly off-script, small, significant moments which veer off the very clear and predictable course. At the centre of the staged performance, directed by Andy Smith and Karl James but according to Crouch’s prescription, is a deliberate eschewing of the text’s own stage directions, and a deliberate lack of likeness between the characters depicted in the script and the actors playing them. And, perhaps, most fundamentally, the script repeatedly tells us that the action of this play takes place in ‘this theatre’ rather than at the geographical locations implied by the story. It is in these gaps that the need for our process of interpretation is seeded.

The concept is intellectually potent, original and layered – and it provides an element of suspense. However, it feels as though, in its theatrical execution, the performance text lacks dramaturgical mileage and ultimately falls a bit short. The necessary thriller twists towards the end and a conceptually clever deus ex machina moment are deployed to engineer a sense of journey in a situation which is by its nature inevitably quite static. These dramaturgical interventions feel somewhat forced and disruptive to one’s attempt to reach the thematic point of the piece. If the play’s thematic focus is indeed somewhere around the notion of salvation / (parental) leadership in dealing with loss (?), there is a distinct lack of closure at the end of this piece. This might indeed be part of the author’s intention – and it passes for an acceptable finale in theatre – but feels at odds with the act of reading itself.

That said, this script is definitely much better read with others, in the course of a live performance, than in the isolation of your own study. So do go along, if you can.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Duška Radosavljević.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.