As the saying goes, “You can’t judge a book by its cover.” In the same way, if you thought the 28-year-old ikemen (drop-dead gorgeous) actor Junpei Mizobata had just been cast to fill seats for the upcoming staging of one of the world’s most well-known but challenging modern plays, you’d be doing a great injustice to a great young talent.

That’s because Mizobata will play a key role in Shintaro Mori’s production of English playwright Harold Pinter’s first box-office hit, 1960’s tragicomic The Caretaker, alongside Shugo Oshinari and Yoichi Nukumizu who play its two other characters.

Perhaps the problem is that Pinter is just so Pinteresque, meaning this giant of the “theater of the absurd” tends to depict human existence through dialogue replete with implied meanings, darkly understated threats, colloquial language, trivialities and long pauses in plays that can be both troubling and confusing.

In The Caretaker, Pinter serves up—with some refreshing humor, too—a psychological expose of the power struggles, loyalties and corruption that ensue when the seemingly meek Aston (Oshinari), a survivor of the brain-deadening electric-shock treatment commonly used in Britain back then to treat all manner of maladies, brings a homeless man named Davies (Nukumizu) back to his garret in an old house in west London looked after by his younger brother, Mick (Mizobata).

Next morning, after Aston has gone out, Mick enters and is surprised to encounter Davies, whom he questions aggressively while the two debate various enigmatic subjects ranging from the sublime to the plain stupid. Later, the brothers separately each ask Davies to be the caretaker, which is very nice—but what would his duties be, and who will be the boss in light of Davies’ already growing influence?

Typical of Pinter’s work, clarification is often lost in long silences or meaningless and sometimes mad conversations—features that, though often reflecting reality, may account for the rarity of such plays here, where people tend to avoid obscurity and absurdity in favor of answers that suit everyone.

To find out what might be in store on this rare occasion, The Japan Times visits Mizobata at a studio in Setagaya Public Theatre’s building in Sangenjaya. There, ahead of eight hours of concentrated rehearsals, the Wakayama native talks about the play, his role as ill-tempered young Mick and more.

“As it’s an absurd play, which is not common in Japan, I was a bit cautious about this role,” he admits. “However, I’ve found that the director, Mori, really grasps the essence of this play, so I can trust him completely. Now we are working closely together to make the gaps convey meaning and to unlock the play’s many other puzzles—and Mori is so good at drawing different things out of actors.”

Yet when Mizobata explains what happens in the rehearsal room, it somehow seems more physical.

“It’s like a baseball team’s special fielding practice, so Mori orders me to say my huge volume of lines faster and faster while he’s also indicating detailed movements at the same time.

“But the more he gives me difficult orders, the more thrilled I become as I try hard to do it all perfectly. Actually, I’m pretty confident I’ll be able to follow yesterday’s orders well this afternoon,” he says with a laugh.

As the actor explains, though, that is just the initial stage in creating Pinter’s world. Once he’s mastered his lines, they will move on to shaping the character and delving into the psychology of Mick, apparently the most ordinary of the three characters and probably the drama’s lynchpin.

“I think he worries about his brother Aston from the bottom of his heart, and feels protective about him because he realizes how good-natured he is even though he’s gradually becoming more and more withdrawn—and that’s even though this doesn’t seem to be the first time Aston’s brought a homeless person back to his room to help them out.

“In contrast,” Mizobata continues, “by nature, Mick discriminates against others in a weaker position in society, such as immigrants and people like Davies, whom he enjoys attacking verbally despite trying to use him for his own ends.

“Actually, even though Davies talks a lot, we think this play is about the brothers, and Davies is just a part of the setting, much like all the junk in the room. So I think he’s like talking rubbish— even though Nukumizu may not like to hear that,” he adds with a laugh.

However, as the cast and director close in on their target of understanding the men’s relationships, Mizobata adds, “Although he’s mindful of him all the time, I think Mick obviously tries to avoid meeting Aston because it upsets him to see what’s become of his once smart and proud big brother and he’s confused how to communicate with him.

“And I believe that kind of dis-communication, that breakdown of family relationships, is still happening generally in today’s world.

“Also, all three are such annoying and fussy guys who’re always making excuses about themselves, yet when I look around in my daily life such people are easy to find. So, it’s an English absurdist play, but you can see it here and now, too.”

“In the same way,” this gifted ikemen continues, “when I acted the young heroine Julia in the great Yukio Ninagawa’s production of Shakespeare’s The Two Gentlemen Of Verona in 2015, she disguised herself as a man to get close to the gentleman she loves. But that would be impossible nowadays as there’s so much about us all online, so I drew on my imagination to conceive how I could be that passionate and desirous.

“Now I am using the same approach with The Caretaker, and I believe I can find the common traits there with our actual lives.”

As he reflected on the heaven-sent opportunities theater has given him—including, he says, hearing Ninagawa’s stories about his time in the 1960s and ’70s radical student movement and how he moved on to channel his rage through theater instead—Mizobata’s eyes really sparkle as he tries to explain the joy he gets from theater.

“When I’m on stage I feel excited about reacting to all the things happening, so I don’t fix my acting plan too firmly beforehand. In fact, I rather welcome unexpected situations, such as if someone skips a line or misses a cue. In such moments I feel a surge of positive tension, and that’s one of the pleasures of live performance—and if I am really living the character, I think I can cope with anything unexpected.

“In fact, no two performances are ever the same, and though the audiences may not notice it, that is such an interesting part of live acting on a stage.”

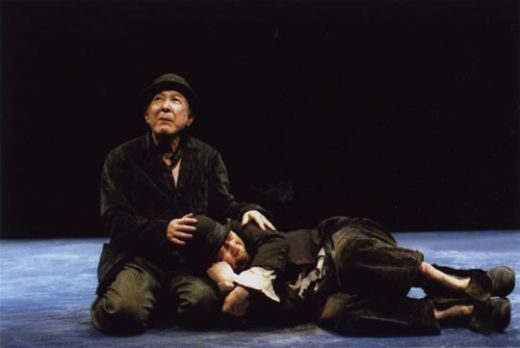

Theater of the absurd: Shintaro Mori takes on Harold Pinter’s “The Caretaker,” an absurdist piece that stars (from left) Junpei Mizobata, Yoichi Nukumizu and Shugo Oshinari. | © SHINJI HOSONO

The Caretaker runs from November 26 to December 17 at Theatre Tram in Sangenjaya, Tokyo. It then plays December 26 and 27 at Hyogo Performing Arts Center in Nishinomiya, Hyogo Prefecture. For more information, call 03-5432-1515 or visit setagaya-pt.jp.

This post originally appeared in The Japan Times on November 21, 2017, and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Nobuko Tanaka.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.