Tokyo has long been the center of Japan’s theatre world, but in 2014, that began to change, with festivals popping up from north-to-south, and artists heading abroad to global acclaim.

Looking back over the past 12 months in Japan’s theatre world, it’s clear that one encouraging trend is a lessening of the capital’s dominance.

Contemporary drama in this country has long been centralized in Tokyo, where major theatres plan their programs far in advance, booking celebrity actors or actresses to appear in works by popular directors — often even before the play has been written.

Predictably, such stagings normally sell out quickly among the same group of people, with the scarcity of tickets being taken as a key evaluation of the production.

As a result, the Tokyo theatre scene — and with it Japan’s — has failed to reach out to a wider audience as a public art, instead of existing as a rather minor subculture for a coterie of followers.

In 2014, however, distinct changes began to reshape this landscape, as regional theatre festivals sprang up from north to south, including I-play Fes in Iwaki, Fukushima Prefecture, Kyoto Experiment and the Kunisaki Art Festival in Oita Prefecture.

In addition, young dramatists such as the award-winning playwright and director Yukio Shiba have left the capital to take their art to people in the regions — in his case to Shodo Island in the Seto Inland Sea, where he is making local participation the norm.

Similarly, Oriza Hirata, who is one of the country’s most influential dramatists, is now busy promoting a distinctive artists-in-residence performing-arts center in the small Hyogo Prefecture hot-springs resort of Kinosaki, where he aims to create new, deep-rooted theatre culture for the area’s seemingly enthusiastic residents and increasing numbers of visitors.

Meanwhile, 2014 has also seen a bright and growing trend for Japanese performing artists to enter the buoyant international market and really make their mark on that global stage.

In this respect, one of 2014′s hottest news items was that the cutting-edge Chelfitsch theater company led by Toshiki Okada, along with Kuro Tanino’s Niwa Gekidan Penino company, were among 33 troupes from around the world invited to stage works at May’s super-prestigious Theater der Welt Festival in Mannheim, Germany — with their Super Premium Soft Double Vanilla Rich and Box in the Big Trunk, respectively. Afterwards, both of these masterful works toured internationally to tremendous acclaim.

In addition, Super Premium — a work that incisively satirizes Japan’s blind pursuit of convenience and meaningless efficiency at the expense of its people’s individuality — broke yet more new ground by having its world premiere at that festival in Mannheim where it had been commissioned, only finally being staged in Japan this month (as reviewed here last week).

And now, if recent reports are correct, it seems that Tanino’s next work will be a play commissioned by a theatre in Krefeld, Germany.

Meanwhile, further exciting evidence of Japanese theatre going global was apparent last year in two great collaborations with South Korean artists.

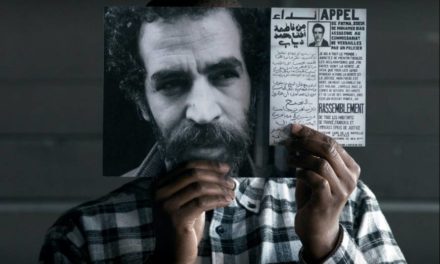

Hideki Noda and cast of Half Gods

One of those was Half Gods, originally written and directed by Hideki Noda in 1986 but produced anew in 2014 by Tokyo Metropolitan Theatre (where Noda is now artistic director) and the Myeondong Theater in Seoul; the other was Karumegi — Korean for “seagull” — a version of Anton Chekhov’s biting 1896 classic of the same name written by Seong Gi-woong, founder of the 12th Tongue Theatre Studio in Seoul, and directed by Junnosuke Tada, whose Tokyo Deathlock company is renowned for its experimental vigor.

Besides the tremendous freshness, these works breathed into Japan’s theatre world when they played here, the sheer quality of their Korean contingents of actors — who almost all study acting at university or specialized colleges — was stunning to audiences accustomed to Japanese casts of gifted but basically untrained individuals.

In fact, if I were to choose my best play staged in Japan over the past year, I would rank Karumegi far and away above the rest due to the outstanding quality of the text’s adaptation and direction — along with the acting.

Originally created by the Doosan Art Center in Seoul in 2013, the play scooped several categories at Korea’s top-flight Dong-a Ilbo Theater Awards, where Tada also became the first foreigner to be named best director in the event’s 50-year history.

All that came about after Tada and Seong met in 2008 when Tada was invited by Korea’s directors’ association to be guest director of an international collaboration project. Since then the pair has worked together regularly, consciously striving to forge a new creative relationship between their countries.

In creating this masterpiece, Seong set “Karumegi” in Seoul during the 1930s, when militarist Japan had annexed the entire peninsular and its inhabitant wavered between near-suicidal rebellion and servitude — in the same way, Chekov’s characters are conflicted between idealism and practical reality.

However, his work is not confined to the past, as it makes extensive reference to the ongoing troubled relationship between the two states that seem so averse to learning from history. In addition, Seong invests this piece truly universal themes he highlights from the original, such as love’s many inherent contradictions, the catastrophe of humans’ avarice and the difficulty of peaceful coexistence in the world as they’ve fashioned it.

As that Dong-a Ilbo award indicates, Tada then directed the work quite sublimely, creating a set with newspapers and other everyday items scattered about in a manner that evoked imagined scenes inside the Sewol, the Japanese-built South Korean ferry that sank in April with the loss of 304 lives.

With its cast of Korean and Japanese actors, the work mingles both’s languages as the characters’ unremittingly busy lives were expertly portrayed through having them repeatedly cross the stage engrossed as if blinkered and hostile just like the two neighboring countries pursuing their own self interests — here to the slightly crazed refrain of Ravel’s “Bolero.”

Meanwhile, although the past year hasn’t see any distinctive new individual star arise, two thirtysomething female playwright/directors — Yuko Kuwabara and Misaki Setoyama — have shown huge promise with works at their Kakuta and Minamoza companies in Tokyo, respectively.

Kuwabara wrote, directed and also acted in her latest play, “Ato Ato” (“Trace and Mark”), which searingly exposes social contradictions as it questions the meaning of life through people in our fiercely competitive society who nonetheless still dream of having an ideal family existence — but whose aspirations are doomed due to missteps they’ve made, or debts they’ve racked up.

On the other hand, in her major work of this last year, Setoyama created an adaptation of a best-selling German novel for children, “Die Wolke” (“The Cloud”) by Gudrun Pausewang. Written in 1987, shortly after the Chernobyl nuclear-power plant explosion in Ukraine, the story looks at life after an imagined similar disaster in Germany through the eyes of a 14-year-old girl (wonderfully played by Mone Kamishiraishi) who is one of its victims.

In her play, titled “Mienai Kumo” (“Invisible Clouds”), Setoyama introduces a new character of her own — a young female playwright from Japan whose role brings the story right back from distant Europe to our own doorsteps here. In fact it is obvious this young character’s commentary is actually based on what Pausewang herself said to Setoyama when she went to visit her in Germany — including the 86-year-old author declaring she’s determined not to die before seeing all her country’s nuclear power plants closed by 2022 as the government vowed to do in response to 2011’s Fukushima disaster.

She also asked her with incredulity why Japanese citizens are not fiercely demanding to know from their government why a mountainous country such as theirs needs so many nuclear plants scarring its seismically active land.

With all their ages in a 10-year span from 35 upward, it’s exciting to think that this year’s standout dramatists — Okada, Tanino, Tada, Kuwabara and Setoyama — still have decades ahead in which to inspire generations of audiences and artists to come.

And even though the country remains locked in its half-century of neither liberal nor democratic Liberal Democratic Party shackles, it’s surely entirely hopeful that such talented dramatists are turning their attentions to that society and questioning, through its living culture, where to go from here.

This article was originally posted at TheJapanTimes.com Reposted with permission of the author. To read the original article, click here.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Nobuko Tanaka.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.