American playwright, translator, and journalist Amelia Parenteau is currently in residence in Paris, France, where she has been writing about the contemporary theatre scene in that city for TheTheatreTimes.com. In her fourth article, she attends a performance of Macbeth, directed by Ariane Mnouchkine and reflects on 50 years of Théâtre du Soleil.

Ariane Mnouchkine’s Cartoucherie, a collection of theaters located in a converted munitions and gunpowder manufactory in Vincennes, is theater paradise. Situated on the outskirts of Paris, it shares the artists’ incubator retreat atmosphere of the Eugene O’Neill Theater Center in Waterford, Connecticut, or Hedgebrook on Whidbey Island, Washington. And yet, for me, it preserves a unique and elusive charm. Aesthetically, it is easy to identify what is pleasing about the Cartoucherie: the four theaters are located on a verdant campus, which also includes rehearsal space, an atelier for choreographers, two theater research centers, and an arts school for children. There are drama bookshops and dining venues in most of the theater spaces, and an abundance of Christmas lights on the buildings’ exteriors, which seem to glow with the otherworldly energy of their environs, rather than regular electricity.

But the Cartoucherie is much more than a pretty façade, of course. The Théâtre du Soleil, the first of the four theaters to inhabit the property, was founded by Ariane Mnouchkine in 1964 with fellow students from the École Internationale de Théâtre Jacques Lecoq. Currently in its 50th season, it is celebrating with a landmark production of Macbeth. The troupe emphasizes the collaborative necessity of theater, and invests years of rehearsal into each project, producing a show approximately every four years.

The troupe’s acting style draws not only from improvisational exercises but also from Commedia dell’arte and Asian traditions of theater, like Japanese masks and puppeteering. Their intense physical training has a tremendous impact on the actors’ performance; the ensemble mentality is visible from the cooperative way that actors work together onstage. Ensemble work is harder to come by in French theater than in American because French actors are traditionally trained to focus on their personal performance rather than that of the group. From its beginning, Mnouchkine’s troupe took ensemble work to the next level, asking actors to assume leadership and administrative roles within the company, and expecting the director to be willing to sweep the stage, need be. Legend has it that Mnouchkine was told by the French actors’ union, when she first proposed her low-budget “theater community” idea, “If you don’t have money, don’t make theater.”

Money, or lack thereof, clearly has not impeded the success of Mnouchkine’s vision. The Théâtre du Soleil is a prime example of the artistic courage that it takes to make quality theater on a modest budget. And Mnouchkine’s motivation has always been personal rather than monetary. In her own words: “I just need to show you [my audience] love.”

This ethos creeps into every aspect of the theatergoer’s experience. From the moment you step off the métro at Chateau de Vincennes, the end of line one, you are transported into another world: one that is more communal and whimsical than your daily metropolitan reality. There is a free “navette” bus that ferries spectators to and from the Cartoucherie, and the theaters invite patrons to come and stay awhile by offering food and drink before and after every show.

Mnouchkine believes that when you welcome people into your theater, it is your responsibility to reassure their “faith in humanity, as well as their need for generosity, beauty, and tenderness.” To this end, there is a hint of innovation and a dash of classicism in every part of the experience, “helping patrons open themselves up to this alternate world. Mnouchkine draws her strength from defying theatrical convention, preferring to use non-traditional theater spaces, such as gymnasiums or barns, to stage her productions and foregoing printed programs for audience members.

On my most recent visit to the Cartoucherie to see this season’s production of Macbeth, I felt like I was stepping back in time when I entered the great hall of the theater, seeing happy groups carrying trays with enormous bowls of “worker’s soup,” meat pastries, and of course “Witches’ Brew,” a proper ale imported from Scotland. Strangers shared tables and chatted amicably over dinner before the show, creating a sense of community before the curtain even went up. There is an elegant honesty to the simplicity of the Théâtre du Soleil’s warm welcome. For instance, the waiters who dish up your steaming bowl of soup are wearing black bowties and pressed white dress shirts. In contrast to the grandiosity of the gilded theaters of Paris, the straightforward charm of the Théâtre du Soleil helps every patron feel at home. Even the hand soap in the unisex bathrooms was on point – not too fruity, not too perfumed, just clean.

The ticketing system is terrifically egalitarian: every ticket sold is general admission, and seats are assigned on a first-come, first-served basis in front of the theater, using a large cardboard real-time seating chart. Although places are assigned, the seats themselves are long rows of wooden benches, lined with practical canvas cushions, so that you are elbow-to-elbow with your fellow patrons.

Mnouchkine does not believe in putting up the fourth wall, and so audience members are regularly able to catch glimpses of actors in the rehearsal hall, rushing around backstage, or putting on makeup before the start of a performance. I was particularly thrilled to gawk at the enormous costume rack in the wings of the Macbeth production, storing multiple costume changes for a cast of dozens. The irony is not lost on anyone that despite Paris’ investment in the accessibility of the arts for all citizens, one of the most welcoming theaters finds itself outside the city limits.

For Mnouchkine, theatre is life, and she has an uncanny ability to keep her focus on the present, as live theater asks us to do, suspending time so that we intensely live with characters in their journe a , moment for moment. She feels that she is charged with ameliorating the world, and she uses theater as a tool to help herself, her troupe, and her audience understand the times we live in. Mnouchkine says, “The role of theater is to show the possibilities, to retell a story, to awaken the desire, the hope, the courage and the appetite of the spirit.”

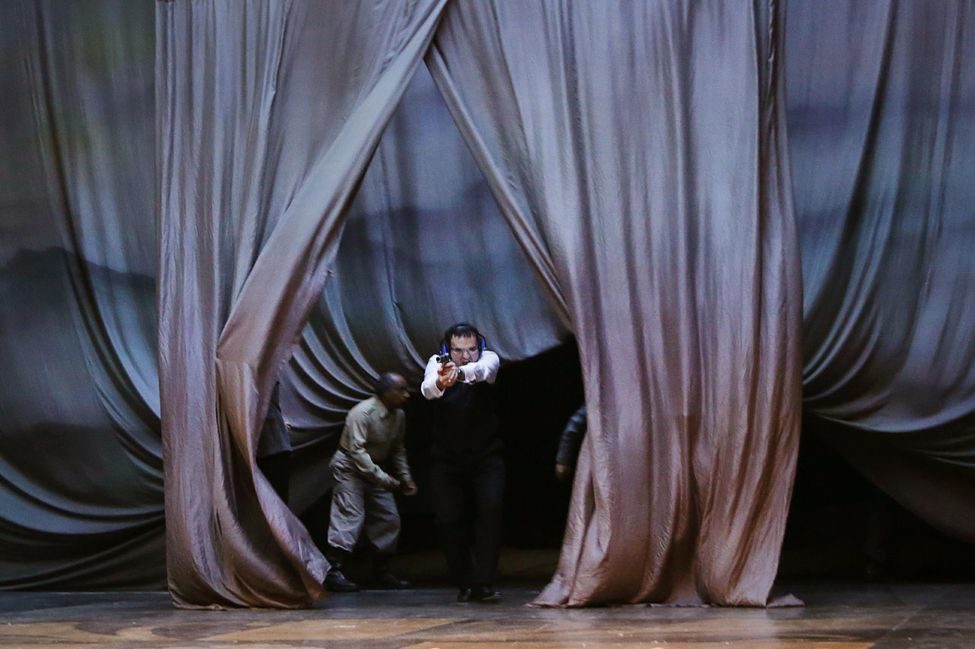

This epic and beautiful rendering of Macbeth certainly achieved these tenets of storytelling and theater-making. I was so engrossed in the action that I was shocked to see how many hours had flown by with me sitting on the edge of my seat. It was the sort of multidimensional production that is hard to come by, these days, and the years of work that went into developing it certainly showed. The scene transitions were magnificently synchronized, with every ensemble member lending a hand, rushing furniture, lampposts, greenery, etc., in and out of beautiful internally-rigged billowing gray curtains. The textures of the materials used to create the costumes and sets were sumptuous, and the witches’ magic was almost believable, with flying plates and flickering lights at the banquet scene. Stark anachronisms, such as the use of a laptop to display Macbeth’s three visions to him, and him alone, gave an appreciable and gentle nod to the contemporary relevance of the story.

As for the text, which was translated by Mnouchkine herself, it was neither Shakespeare’s English nor sixteenth century French, but rather a lyrical modern French. The poetry cannot exist in the same way that it does in the original text, not only because the meter and rhymes of the words are different, but also because the very cadence of French is different than that of English, which changes the auditory experience. That said, the flavor of the text remained, with its rhythm and intrigue furnishing the highs and lows of the storytelling. There were a couple of sequences where directorial choices/cultural differences changed the mood of a moment: when Macbeth learns of Lady M’s death, for instance, the translation of “She should have died hereafter,” as “Qu’elle soit morte un autre jour,” brought a laugh, rather than a sigh, from the audience. Overall, however, the translation and direction were faithful, and like any quality production of Shakespeare, once you fall into the rhythm of it, you’re along for the magnificent ride.

Fifty years since their first season, the Théâtre du Soleil has welcomed 57,818 patrons this year. Given Mnouchkine’s devotion to the powerful and brilliant work she and her troupe are doing, I don’t predict that retirement will be in the cards. That said, Mnouchkine has heavily invested in a gifted young director named Hélène Cinque who stages shows at the Cartoucherie almost every year. Two years ago, I had the privilege of interviewing Cinque, who told me that the biggest directing lesson she learned from Mnouchkine was to do what you feel you must, without compromises. If you are not demanding, you’ll never get anywhere. Cinque is continually inspired by Mnouchkine’s energy and absolute conviction in the work she creates. In addition, Cinque relayed that Mnouchkine taught her the notion of a theater troupe is essential. “We live in such an individualistic society, even more so now than when Mnouchkine founded the Théâtre du Soleil in the 60s,” Cinque said.

And it’s true: above all, I am most impressed by the ability of this theater to create community among strangers, if only for an evening. Everyone is in it together, and people are generally more open with each other. I’ve gotten into more conversations with strangers going back and forth on the navette to the Cartoucherie than in all my months of riding the métro. Mnouchkine is an unabashed idealist in the way she steers her theater community, and her tremendous, enduring success comes from the magic of investing in people’s happiness.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Amelia Parenteau.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.