José Luis Raymond is a multi award-winning Spanish Stage Designer, Director, Plastic Artist, and Professor of Stage Design at the Royal School of Dramatic Arts (RESAD) in Madrid. His theatrical career started in 1975 and he has been a reference in the Spanish and European Theatre for decades now.

How did you get started in the theatre? What people influenced and inspired you along the way? Any seminal teachers and mentors?

Since I was very young, my way to communicate and express myself artistically has always been through plastic art and theatre. They both still produce in me an almost childish fascination when experimenting with materials and new forms of expression. The combination of both disciplines continues to be an individual process of analysis, from painting to sculpture, from staging to scenography.

All these materials I’ve been working with were already a part of me, of my expressive world. In my search for identity, doubts emerged about which paths to follow, which models to study and which ones would be the closest to what I wanted to, if not imitate, at least understand.

In the 60s and 70s, Spain was going through a dictatorship and plastic and theatre research was going in many different directions, with some opinions against tradition already arising. Spanish independent theatre initiated us all with the expressive means they had and would be key for the development of our theatre’s new direction.

And there I was, in the middle of this political and cultural crossroads trying to figure out how to implement the theatre I wanted to develop. At school, I had already staged my own experimental work, relating plastic art with theatrical narrative action. My studies in French helped me to further develop this way of understanding the scene: telling stories from a plastic perspective.

While at the Fine Arts school in the Basque Country, theatre and plastic art definitely cohered as the basis of my current thinking. Plastic artists who worked with physical volume and theatre makers who managed space were the ones who started me on the path of body and space: Edward Gordon Craig, Adolf Appia, the historical avant-garde, etc. They all had an influence in what I am today.

In the 80s, the figure of the Polish artist Tadeusz Kantor and all the artistic movements in the communist countries of the time put me on the track of “plastic art theatre” as possible, alive and tangible. This led me to found my own theatre company in Bilbao, as well as the Getxo Theatre School.

This knowledge later drove me to live in Poland for several years under a scholarship that allowed me to follow closely the plastic-theatre studies which were being developed there. This life experience made my way of working with space, objects, and characters more expressive, and helped me discover other international artists who continue developing multidisciplinary artistic processes.

When you began working professionally, what was happening in theatre in Spain? Were there particular trends, styles, themes, methods of working?

After my time in Poland, which I finished the year of the fall of Berlin’s Wall (1989), I went to Amsterdam to learn about another culture of arts integration and I met creators that worked with other scenic materials. There I knew, for instance, Mykeri, an experimental space, a place where all theatre makers in the world went and where you could find a cultured society prepared to experiment with their cultural and performing arts, giving them a new life and renewal.

After some time in this country, I landed in Madrid. The drought in the city’s experimental theatre was clear, but glimpses of renovation attempts were also seen in some theatre shows. The first alternative theatre Cuarta Pared (Fourth Wall) opened in the city. I was designing my first commissioned scenography for David Mamet’s American Buffalo, with Fermin Cabal as the director at the Alfil Theatre in Madrid.

Theatre artists in the city struggled to live with the little remaining independent theatre there was the traditional commercial theatre and the national theatres. At that point, there was collective madness to work at Seville’s 1992 Universal Exposition. I was already working as a scenography teacher at the RESAD (Royal Dramatic Art School). In my classes, the body was the object and acting students in those early 90’s began their professional career with new ideas on theatrical space.

A new process to establish theatre studies officially was beginning: stage direction and dramaturgy, scenography, acting, all these programs finally acquired university status, equivalent to an undergraduate degree. This event in itself has made possible the development of further performing arts investigation in recent years, as well as the need to professionalize the Spanish theatre culture, as much in creation, as in scenic architecture and research.

In 2014, we had close to 40 alternative spaces to work at with different scenic proposals. Today, 25 years after arriving in Madrid, I can work with all kinds of theatre professionals trained in new plastic-theatrical trends, just as I would have needed when I first arrived in town.

Teaching performing arts has really been worthwhile. It’s the breeding ground for the individual’s creativity and development within his or her own environment.

José Luis Raymond. Photo by Vicente Paredes. Courtesy of José Luis Raymond

In hindsight, how has your particular theatre profession changed throughout your career? What impact has the advent of digital technology had on the design process?

The theatrical designer’s profession has changed, as has the study of scenography and other performing arts disciplines, like acting, stage managing and playwriting, which became college degrees in 1992, with the first performing arts promotion graduating four years later.

This means that when works have been more creative and technical, they’ve been supported by more professional resources and training, forcing our field to respond to greater demands in all areas in which scenography is present: lighting, mapping, design, costume, etc.

Concerning my personal work, my process has evolved as I made discoveries and mistakes, which became creative-educational procedures in my everyday theatre pedagogy.

In my pedagogical practice, the findings in new textual and visual playwriting, as well as in aesthetic and technical concepts, are tools to develop new scenic creations. As these tools are imbued by the feel of theatrical creation, new development values are produced. Electronic effects add other dimensions to the storytelling, while audiovisual media and scenic technical management help develop new scenic paths. And I would add that digital technologies are also becoming instruments to develop creative thinking and its design.

Tell us a bit about how your approach working on a play? How does the process begin?

The stage, the scenography, and the staging are my references when working in performing arts. If I have to direct a show, like an opera or contemporary music or text, I translate into images its total essence, its conflicts, and ideas. As I see everything in images and in space, the first thing I try to solve is the aesthetic and the formal conflicts, where text and characters will be. In general, I’ve never been interested in the Aristotelian narrative to tell stories. Abstraction has always been my ally and where I feel most comfortable.

When my job is to create a theatrical space, my role is to fulfill the stage manager’s ideas and concepts. Through the first ideas, all that has to be related or whatever it has to be told through scenic display, that is to say, all the elements on the scene ought to have the consistency of thought and style to reach the chosen set.

But before going into the final process of creating the staging, you have to read the play, analyze it, set out all the ideas concerning the process, style, meanings and hierarchies of the scene, whether you want to focus on a certain object, light, sound, word, a certain movement, etc.

Based on the work with the director and through graphic ideas such as sketches, models and visual references, the creative process improves; very often the entire artistic team is part of such a process. Dress rehearsals, good and bad choices, the play production and the other components are the things that lead us, slowly and stumbling at times, to the final staging and the play’s premiere.

Grita. Un espectáculo en tiempos del sida (Scream. A Show in Time of AIDS) Written and directed by Raymond. 1995. Courtesy of Spanish National Theatre.

What do you look for in a director and other designers when collaborating on a play? Do you work with the same people over and over, or do you seek out new colleagues to work with?

Through my experience, here and abroad, what I expect from a director is to be able to work together from the same starting point of the process. In other words, to have an intellectual understanding and to walk together the same path, as much in the creative, ideological and aesthetic thinking, as in the spatial and creative sensitivity, open to new scenic proposals… without fear! I mean, people who know the environment in which they work and take the stage set into account.

If I work with a designer, the same applies. I need people who can work from a management and a staging point of view simultaneously. They both must know that space, action, and word are joined together when telling a story and that this space is not only the place where to set up a design to serve the performers’ action.

I usually work with the same professionals or with new ones that have that creative ideology I was referring to earlier. I’ve worked with many directors and not with all of them I’ve had that same process of creation, which has often led us to disagreements. But that is also part of the theatrical event when working in such a short time with so many people that have to do their job before the curtain is raised.

Being a profession that constantly deals with emotions and feelings, the disagreement may run high but that is when professionalism allows us to approach each other to complete our objective: the show!

How do you deal with the pressure and stress of working in the theatre?

The show must go on, as they say! It’s true that there is always tension when the time is so present throughout the creative process. Writing, designing, composing, performing, they are all processes that are individual in the beginning and become collective later on. There is also a social component besides the creative one, which penetrates the author’s soul and makes wimps out of the artists with their critics.

Time and experience help endure the scars in our bodies and we feel like warriors having stress as part of our creative task. Fortunately, war wounds do finally heal, though our body often feels like a battlefield.

Have you ever worked internationally? What similarities/differences did you experience with the way you work in Spain?

Stress is here and there; it goes with me! I know I generate my own stress with my goals and desires. I studied at the School of Fine Arts of the Basque Country, and in Warsaw, I learned about Tadeusz Kantor’s plastic theatre and the Polish spatial performing streams during the last years of communism. There I also learned about the social value creators receive and have also for each other. After that, the Netherlands offered me experimentation, the future, the social, artistic, professional and multidisciplinary respect.

Working in London at the Middlesex University, I understood how theatrical arts education should be at the service of all professions that make a show possible. In Washington, staging El Caballero de Olmedo, I learned how interested the public was in our authors and the respect they had for their profession.

Stage design for Tejido abierto – Tejido Beckett, directed by Jorge Eines. 2009. Courtesy of Jorge Eines

Teaching a course in staging and scenography for the Performing Arts Masters program in Bordeaux, I understood that with education sponsored by the state, a social base can be created where culture, experimentation, and creation may form the pillars of emotional well-being.

For a while now Spain has developed respect, education and theatre research. Teaching performing arts in schools and universities have made these concepts possible with calm and innovation. You only need institutions to support with the same interest those needs the society demands.

What is your favorite production that you have ever seen and why?

You ask me about the plays that have made an impression on me or have influenced my way of thinking and working. There are a few, probably because in every period my interests have been different. For instance, Quejío by Salvador Távora, The Dead Class by Tadeusz Kantor, Brecht’s Threepenny Opera by T. Study of Warsaw, Querelle by Lyndsay Kemp, Einstein on the Beach by Robert Wilson, DV8, Romeo Castellucci, Need Company, Jan Fabre, etc.

As you see, all of them are plastic theatrical creators for whom image is the generator of the scenic conflict and they all work in an interdisciplinary manner.

What is the biggest misconception people have about your profession?

The set designer’s tradition comes from curtain painters as traditional theatre spaces used two-dimensional images for storytelling. As spatial and theatrical research has created new playwriting languages and art has brought up other “ways of doing”, also produced by social needs research, the creators of spaces or “set designers” have developed new ways of telling stories. But not all the public or the Spanish theatre professionals understand these new artistic concepts, therefore set designers are still called “decorators” (term used in the film industry).

Sometimes we are also called choreographers! Hahaha. And sometimes we are that too, as we draw the space with the actors’ bodies, as E. G. Craig expressed in his protocol “The puppet actor.”

José Luis Raymond. Courtesy of José Luis Raymond

What excites you theatrically today? Has that changed over the years?

I have an innate curiosity to see and understand new plastic theatrical processes, to know different and creative thoughts that for whatever reason are set up to teach us ways to understand stories.

Under this premise, I go to see and enjoy what creators have staged. I like to be surprised, to have set out new performing issues of any kind, I like craftsmanship, creativity, research and above all credibility in their performing manner.

Therefore, I’ve changed because my life has changed and because art and society have done so too. Also, I’ve been seduced by artistic personalities that have confronted me with the challenges of perfection, communication, and management of my own tools – used in my profession- such as being a professional in art teaching and in performing arts.

Whose work do you admire most right now and why?

Like I said before, my admiration for some scenic creators has developed as I’ve changed through my understanding of them. I mentioned some of these artists before when you were asking me about my scenic references.

This list does not exclude others stage creators, as I also learn from lesser-known artists that show their own theatrical vision in any demonstration related with performing arts, playwrights, set designers, stage managers, lighting, etc.

Besides the already consolidated stage creators who have left their imprint in my way of thinking and developing my daily work, new artists that appeared through social networks are making their way to understand art through this new technology. And among these, the American, John Jesurun, or the new text-object playwriting of Angélica Liddell, Rodrigo Garcia, or La Veronal, but I still follow those plastic artists who show me new concepts to further develop the scenic and staging activity.

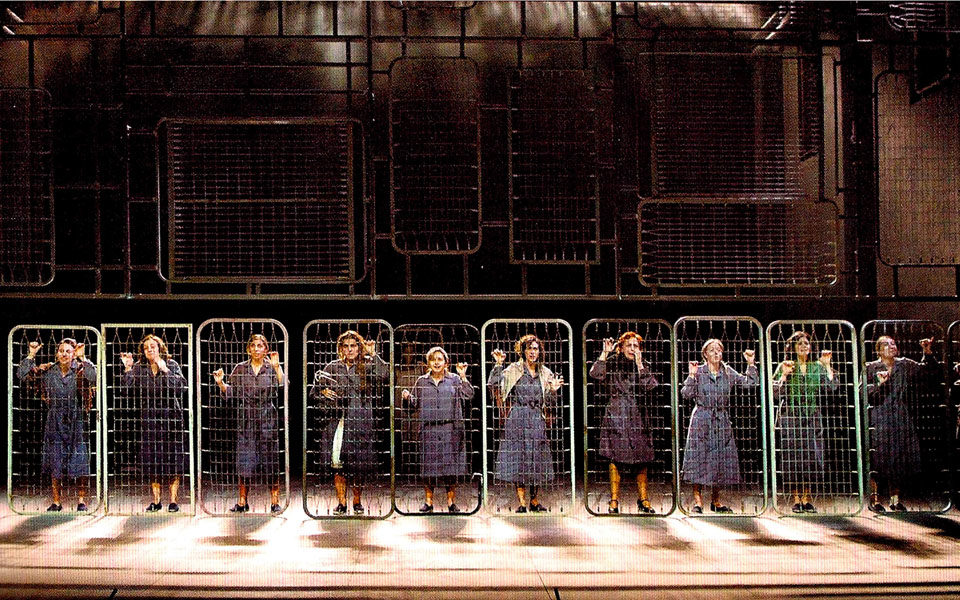

Montenegro by Ramón del Valle Inclán. Directed by Ernesto Caballero. Scenic design by J.L. Raymond. Spanish National Theatre 2013

What are projects are you currently working on, or in development for?

I just finished a scenography with Ernesto Caballero, a Spanish author, and director of the Spanish National Drama Centre, for the work Montenegro, a free version of Don Ramón del Valle Inclán’s trilogy The Barbarian Comedies.

Moreover, I’ve been appointed as Spain’s national curator for the Prague Quadrennial 2015. The Quadrennial is dedicated to theatrical scenery and architecture and will be held in June 2015 with the participation of 70 other countries.

I am also preparing a collaborative project to work with other theatre makers in which interdisciplinary work will be the basis of the creative process. All in all, I keep putting into practice the ideas I believe in.

If money where no object, what would be your dream project, and who would you like to work on it with?

You always need money when starting a project and especially if you want to show a product of certain quality. Being based in the Spanish independent theatre during the 80s, our lack of money and creativity were the necessary allies to put productions together and to show them as milestones for having reached their premiere.

I’ve worked and continue to work in large theatrical productions and in plays where illusion and belief in a well-done job invade you through the group’s vocation. My dream project as a set designer and scene director would be to develop a research process over a long period of experimentation and rehearsal.

What piece of advice would you give to a young person just starting out in your profession?

As creator and as teacher I tell my students that the theatre and its different artistic components will last them a lifetime, that these studies are long distance runs, where the towel will be their companion: sometimes they’ll use it to dry up their sweat and sometimes they’ll want to throw it away, to give up (Spanish expression that uses “throwing the towel” as metaphor for “giving up”). But resistance, curiosity, and experience will be assets that will accompany them all the way in their creation. Art and life are words that will run through their veins in their career, without forgetting who they are and where they come from.

José Luis Raymond at work. Courtesy of J. L. Raymond

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Beatriz Cabur.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.