In the world of Japanese contemporary drama, the action often takes place offstage as well as on.

A case in point is what happened to Chiaki Soma, the program director at Festival/Tokyo from 2009-13, who is the main force behind the Theater Commons Tokyo festival, now in its second year.

Soma found herself caught up in an unfolding drama when she returned to F/T from maternity leave in August 2013 — only to be told she would be relieved of her position after that year’s edition. Reasons for her dismissal were unclear, but in an interview with The Japan Times last year, her successor, Sachio Ichimura, disclosed that though Soma did the job of programming “splendidly … she didn’t have enough experience dealing with bureaucrats.” Soma became a freelance theater producer in April 2014.

New forms: Chiaki Soma had an epiphany of sorts after a successful four-year stint heading up Festival/Tokyo. ‘I no longer believe that merely presenting work under the umbrella of a festival is the best way to attract new audiences,’ she says. | NOBUKO TANAKA

“Over the past 15 years I’ve been working through theater and other performing arts to project an idea of today’s Tokyo to the world, and bring the world here,” Soma, 42, tells The Japan Times at a cafe in Tokyo’s Sugamo neighborhood. “I think I succeeded to an extent through my programs for F/T, which were well received by audiences.”

Rather than dwelling on the drama, Soma says the whole affair provided her with an epiphany.

“I finally realized Tokyo didn’t need me at all, especially since some of the more free kinds of theater I like — such as experimental town walking or site-specific programs — were becoming difficult to do because of security concerns surrounding public spaces ahead of the 2020 Olympics.

“Now, I no longer believe that merely presenting work under the umbrella of a festival is the best way to attract new audiences or create the best platform for the kind of theater that directly affects people’s lives. After all, most of the audience is likely to be educated and financially and socially blessed, and in that kind of Trumpian setting live theater typically just re-presents reality without actually affecting society.”

Soma’s aim to, as she puts it, “activate the personal experience of participants more deeply and enrich their lives through the activity of theater” led her to start a nonprofit called Arts Commons Tokyo (ACT) in 2014.

Since then, along with an array of Japanese and non-Japanese colleagues, she has been using the ACT platform to create grass-roots theater projects that directly involve participants — such as workshops, lectures, art seminars, fieldwork camps, and symposiums.

However, a yearlong stint teaching drama at Rikkyo University in Tokyo’s Toshima Ward in 2016 brought about yet another radical shift in Soma’s focus when she realized her students knew about ballet and piano but they hadn’t heard of iconic theater director Yukio Ninagawa (1935-2016).

“I began to think about giving people opportunities and experiences that could be created by using theatrical methods — rather than just hoping they’d one day buy a ticket to see a play or something,” she says.

As a result, in 2017 she used ACT to create Theater Commons Tokyo as an annual event that could attract audiences by offering more interactive programs, workshops, and lectures together in a single package.

To Soma’s delight, that inaugural edition of Theater Commons exceeded her expectations, with one of its audience-participation programs — a theater workshop titled “Performing the Japanese” run by visual artist Hikaru Fujii — winning the Nissan Art Award.

As Fujii explained at the time, his piece was inspired by “Academic Museum of Mankind,” a notorious 1903 exhibition in Osaka in which living people were displayed as examples of different kinds of humanity, such as the Ainu and Ryukyuans. To make his piece, Fujii videotaped participants dividing themselves by appearance into groups of “typical Japanese” and “atypical Japanese” — with the former then walking around discussing silent “exhibits” from the latter group so everyone could experience society’s tendency toward segregation. Afterward, using the video, photos and other historical items, he created the award-winning installation.

This year, Theater Commons features nine programs — with four from Japan and the others by Moroccan-French, French, Malaysian, Taiwanese and Dutch artists — together with a range of talks, meetings and symposiums.

Fujii returns with “Piraeus/Heterochronia,” a video work he created by filming in Piraeus, a port city near Athens. With a population of 449,000, the city currently serves as a gateway to Europe and is simultaneously experiencing an influx in refugees and an economic crisis. The video delves into the stories of the people there and the complex nature of time.

Alongside Fujii’s work — and a two-day workshop examining the relationship between “private” and “community,” hosted by artist Meiro Koizumi — another of Theater Commons’ Japanese contributions comes via an updated version of promising director Yuta Hagiwara’s award-winning “Happy Days (Act Two),” his 2016 take on the Samuel Beckett play with his Kamome Machine (Seagull Machine) company.

Picture perfect: Meiro Koizumi’s, whose work includes ‘Portrait of a Young Samurai,’ will feature at Theater Commons Tokyo. | © MEIRO KOIZUMI

Rounding out the Japanese offerings is one of three “lecture-performance” programs on Theater Commons’ roster this year: “Nippon Cha Cha Cha!” In this solo work, artist Yasumasa Morimura — best known for self-portraits in which he portrays famous people — explores his own life story and this country’s postwar history and art while himself appearing in guises that include Marilyn Monroe, Yukio Mishima,

and others.

Dressing up: Yasumasa Morimura is known for taking self-portraits in which he takes on the guise of famous people.

In addition to Morimura, French artist and musician Julien Fournet will present a lecture-performance as part of a piece that runs over three days. Alongside his own guitar accompaniment, Fournet, director of the Lille-based communal theater company L’Amicale de Production, will stage three different shows titled “Friends, let’s have a break” in which he examines contemporary society and the role of the arts.

Guitar man: Julien Fournet will stage three different shows titled ‘Friends, let’s have a break’ at Theater Commons Tokyo. | © BEA BORGERS

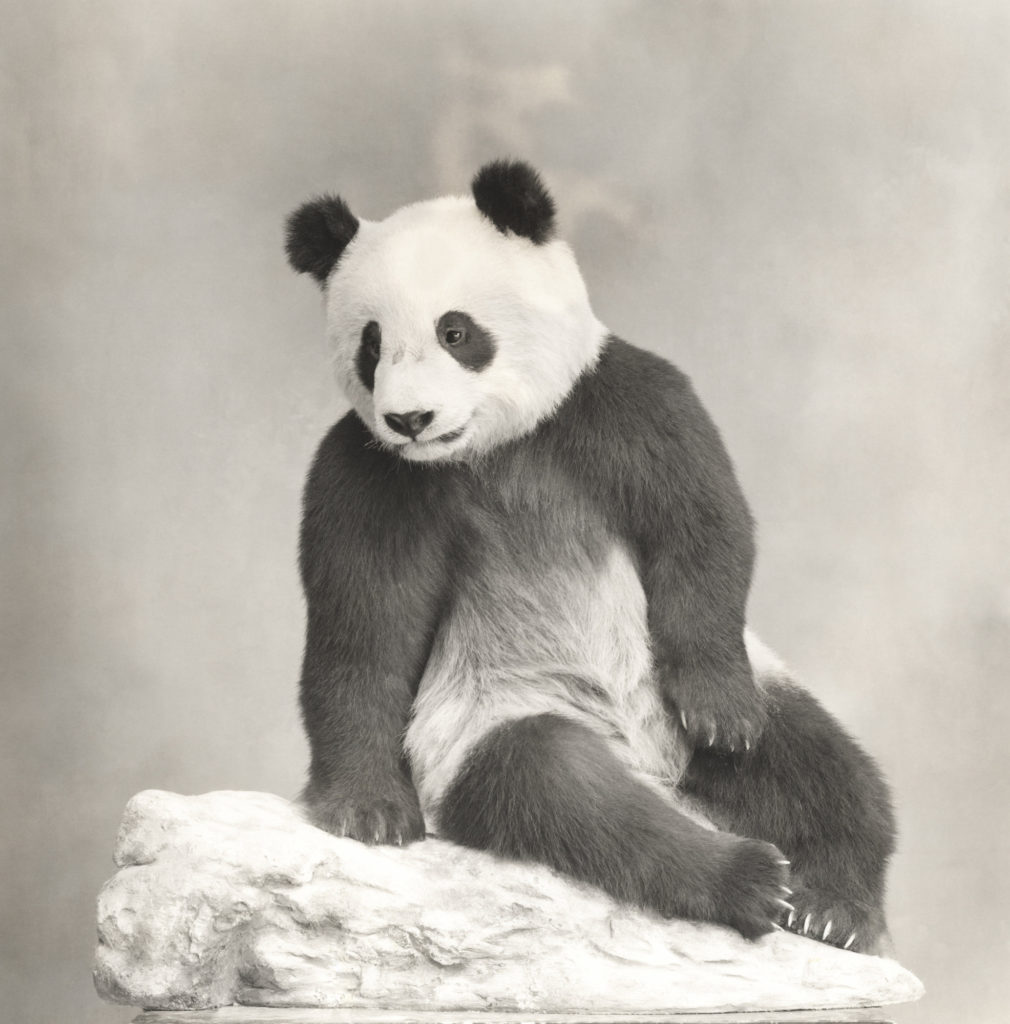

Completing Theater Commons’ lecture-performance lineup will be “Black & White — Panda” by the incisive and award-winning Taiwanese visual artist Hsu Chia-Wei, whose piece examines the political significance of China’s so-called panda diplomacy and its hidden history relating to Tokyo’s Ueno Zoo and a zoo in Taipei.

Animal art: An image from Hsu Chia-Wei’s ‘Black & White — Panda.’

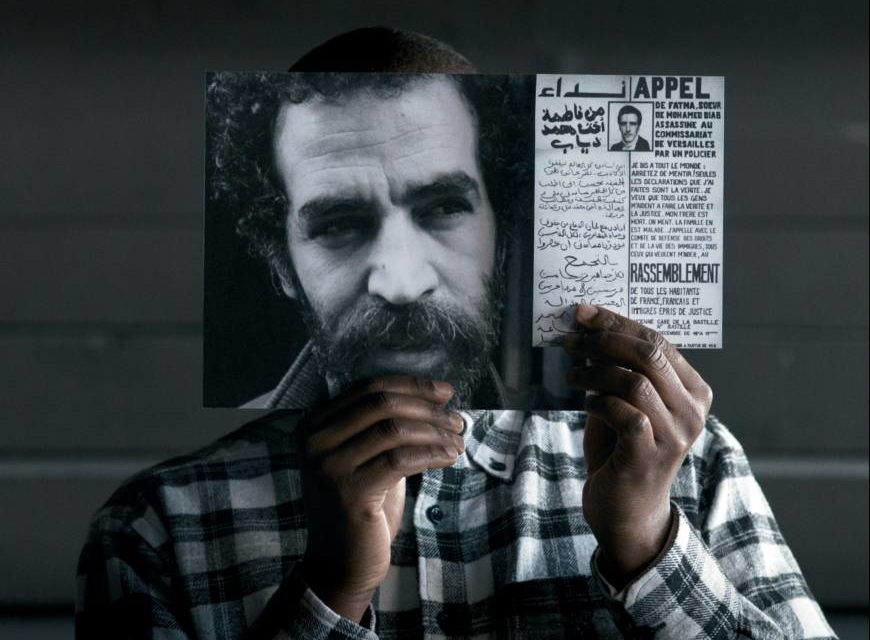

Rounding off the roster are a documentary-style film about immigration titled “The Tempest Society” by Moroccan-French artist Bouchra Khalili; “Version 2020 — The Complete Futures of Malaysia Chapter 3,” a theater work by the acclaimed Malaysian director Mark Teh, who examines aspects of the controversial administration of Mahathir Mohamad from 1981-2003; and “Hello Atmosphere,” in which the Dutch company Theater Artemis opens a workshop for elementary school children.

Keeping in mind her own experience at Festival/Tokyo, Soma sums up by reflecting on the state of theater in Japan.

“It has become more and more conservative, and the mainstream theater world has grown more stagnant, so I want to break out of this sluggishness by helping to foster a style of theater that works directly and deeply on each person,” she says. “And though our movement so far is a very small step, one day I want to run a theater that has that new kind of mission.”

This post originally appeared on The Japan Times on February 22, 2018 and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Nobuko Tanaka.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.