On a pavement alongside a busy road, a line of people march one behind the other. The person at the front holds a long blue and white striped cane at waist height, horizontal to the ground, and spins as she moves forward. The people behind follow the person in front and are linked together but also separated from one another by equally long black canes which they carry; one hand holds onto a handle strap of the cane in front and the other hand holds onto the handle strap of the cane behind. The progress the line makes is slow, the speed mediated by the person in front as she moves forward, spinning and also negotiating street objects and people on the way. After approximately one hundred meters a ceremony of exchange takes place. The person in front stops, turns to her right to face away from the road and holds up the striped cane vertically in the form of a salute. She then hands the cane over to the person immediately behind her and walks to the back of the line. With the new front person, the march starts all over again, the leader spins and moves forward pursued by the line of connected followers. This activity is repeated for twelve stops over sixty minutes and comes to an end when one circuit of the pavement has been completed.

The happening described above, titled 12, began at twelve noon and took place on the twelfth of May, 2021. It was enacted by students in the first year of a BA Arts Management course.[1]As part of their studies in the second semester, the students did a 30-hour component that promoted artistic involvement. The title of the component was Creative Involvement Through Happening. The happening was specially prepared for the twelfth Between.Pomiędzy Festival of Literature and Theatre and one of the themes it explored was the COVID-19 pandemic, which has caused restrictions and lockdowns to be imposed all over the globe. The initial concept for the enactment arose in April 2020 out of discussions with second-year students who were on the same course. During the first wave of the pandemic in Poland and the lockdown that followed, there were obvious discrepancies between what was “enforced” and what people actually did, as there has been throughout the pandemic. For example, people kept a two-meter gap while waiting in a line outside of a supermarket but abandoned the rules of distancing once inside the shop. With the second-year students, it was decided to create a happening that would encompass ideas of restriction and keeping distance. This resulted in Restricted Sightings, which also referenced research into space instigated by Oskar Schlemmer at the Bauhaus in the 1920s.[2]A considered view of Schlemmer’s research at the Bauhaus is given in: Małgorzata Leyko (ed.), Schlemmer. Kantor. Cricoteka, 2016. It has the additional merit of showing links between the creative … Continue reading In the enactment of Restricted Sightings, the author of this text visited a number of students close to their homes and walked and spun with a cane while the students bore witness to the enactment by documenting it.

Restricted Sightings – bearing witness through documentation. Photo: Tymoteusz Buhl.

A year later, and for the happening 12, distance and restriction again played an important role. On closer inspection of the objects used in the happening, it could be noticed that the striped section of the blue and white cane was divided into two hundred one-centimeter sections, which meant the person holding it and spinning kept a two-meter distance from the people and things they encountered. The people in the line, meanwhile, carried canes that also allowed a two-meter distance to be maintained. Everyone wore masks and in all the activities attendant to the happening, care was taken to avoid close contact. Indeed, unlike the previous year’s happening, which took place between the author spinning and one student witnessing the action, there were more participants in this happening and the contact between them was less “intimate” – they walked as if they were part of a machine which moved slowly along a predetermined route.

Of course, this “work together apart”, with an eye to uphold prevailing sanitary recommendations, was an important aspect of the script for 12, which meant the university authorities gave permission for the enactment to take place – a necessary consideration since the participants were students and the happening made its way around the outside perimeter of the University of Gdańsk campus. However, limiting the meaning of the happening to generalized tropes connected to the pandemic, would cause other individual understandings and experiences to be lost. This is especially true of the interpretations[3]The interpretations were included as reflections in a portfolio which students had to complete in part fulfillment of the component. offered by the student-participants concerning 12. And, although their responses did not display a ricochet of ideas that Sayre[4] Henry M. Sayre, The Object of Performance: The American Avant-Garde since 1970. University of Chicago Press, 1989, p. 23. claims can result from contact with performance art, they did reveal a range of concerns, including how the participants felt they were challenged by the enactment. A situation, perhaps, which confirms Limon’s[5]Jerzy Limon, Piąty wymiar teatru. Słowo/obraz terytoria, 2006, p. 131. Additionally, Limon devotes the third chapter of his book to performance art in comparison to theatre. The chapter is titled … Continue reading view that the je ne sais quoi of such art is its ability to provoke and, in this case, elicit different and contradictory views from the participants who took part.

For instance, a number of students commented upon the various ways in which involvement in the happening raised their awareness of the urban environment. One person commented that it demanded care from the participants who, while spinning and walking with the two-meter-long cane, had to be acutely aware of other people and objects. This ensured participants avoided damaging objects and hitting people, although one student-happener did admit a near-miss with a man on a bicycle. Once they had settled into the routine of the happening, the participants also noticed the reactions of other people: a driver’s “honked” approval in a passing car or the anger of a woman walking along the pavement who demanded to know what the happeners were doing. One student even commented upon a raised state of consciousness in which she noticed how her fellow happeners expressed their individuality through the uniform and repeated actions they had to perform. In contrast to this, another participant commented upon the loss of agency he felt by becoming part of such a “large” collective endeavor – he had taken part in a rehearsal the week before and, because the group was smaller, he believed he had a more personal contact with the people involved.

Other reactions among the participants concerned the symbolism of the enactment: the twelve of the title and the routine of the salute, as well as the organization of the happening. For one student, the number twelve was viewed to be “about circularity and time […] [with] deep roots in different myths, religions and traditions (like the 12 Olympian Gods, etc.).” For the same participant, the link to time was emphasized by the fact that there was a dominant clockwise movement, both in the direction the marchers headed around the pavement and the fact that the lead people always spun to the right, providing a choreography that “was very simple, and yet complex [in the meanings it allowed – MB].” In the script for the happening, the number twelve had been aligned with various elements – the theme of the festival, the duration of the pandemic, the date and starting time of the happening and the planned number of participants. However, in opposition to the student who believed the form of the happening and the numerical reference engendered meanings, another participant found the symbolism to be forced, with the number twelve only being appropriate because of the date upon which the happening occurred, while “the whole narrative fell apart when there weren’t 12 people participating in the performance.”[6]The script for the happening stipulated twelve participants to be involved in the enactment, while other participants would be engaged in the documentation. Before the happening, it was apparent … Continue reading

In connection with the salute, some student-participants saw it as a misplaced reverence for the University of Gdańsk, towards whose buildings the raising of the striped cane was directed. One student felt the honor thus bestowed was not deserved, while another person mentioned “the cursed monument of the academy.” Other participants did not view the ceremony in this way: someone, for instance, mentioned that when the salute was given in one particular changeover, a McDonalds stood in the way, so that “with the current affair surrounding the company – you could interpret it as an Anti-capitalist performance”. Yet other comments made by the student-participants focused upon issues of organization linked to carrying out such a physical enactment under a hot noon-day sun. For two people, it was also the discomfort they felt after having recently been vaccinated against COVID-19. Thus, engagement in the happening became a vehicle for the consideration of health and safety issues related to the extreme weather, as well as dealing with the side-effects of a vaccine. Another participant, meanwhile, saw this physical endurance as a potent metaphor for the situation experienced by everyone throughout the pandemic, while, striking a more neutral tone, one student saw the happening as providing “a space, a reason, and a basic tool to rethink what that time [the pandemic and lockdown – MB] actually was for us”.

12 was the eighth in a series of happenings that have been presented under the banner of the Between.Pomiędzy Festival of Literature and Theatre. These happenings have been specially prepared to take into account the themes of the festival or issues related to it. In previous years, for example, the nature of being “between” was explored in the enactment – 2 Suited People 2 Yellow Suitcases (2012) – which saw two protagonists planting signposts on a shoreline to an in-between place – the pier in the northern Polish seaside resort of Sopot – and then, on the pier, carrying out a forensic search of each other’s pockets, the contents of which were displayed for all to see. In another performance – Wyspa / Island (2019) – which investigated themes of territory and migration, participants created an island space on Sopot pier where they could sit and wait, complete a jigsaw puzzle of the world or become involved in a duel of words reading out a scene from Shakespeare’s The Tempest – switching between the English and Polish languages. Other happenings took as their starting point various plays by Samuel Beckett (a towering presence accompanying each edition of the festival), which were re-presented taking into account the interpretations of their participants (“dramaturgs”). In this vein, there have been enactments inspired by What Where – What Where Re-Actions (2013), Breath – Catching Breath Along A Pier (2016) and Samuel Beckett: The Complete Dramatic Works[7]A compilation of the playwright’s drama texts: Samuel Beckett, Samuel Beckett. The Complete Dramatic Works. Faber and Faber Limited, 2006 [1986]. – The Complete Works (2017), in which participants presented reactions to a chosen play from a compilation of the playwright’s drama texts.

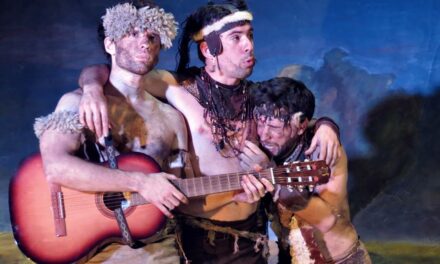

Clockwise from top left: 2 Suited People 2 Yellow Suitcases. Photo: Ewa Blaszk; Wyspa-Island. Photo: Oliwia Woźnicka and Sonia Rembas; The Complete Works. Photo: Malwina Kamińska; Catching Breath Along A Pier. Photo: Iwona Karpińska; What Where Re-Actions. Photo: Ewa Blaszk.

Many of the happenings created for the festival have been presented on Sopot pier, while others have taken place in a Sopot shopping mall or on the campus of the University of Gdańsk. They have also entailed cooperation between the author and actors, as well as students from a range of courses – Arts Management, English Language (Teacher Specialisation), American Studies (Culture Specialisation) – who took part in classes which explored creativity and happening. In addition to this, the form of involvement in these happenings has varied. On the one hand, as in devising,[8]Deirdre Heddon and Jane Milling, Devising Performance. Palgrave Macmillan, 2006, p. 3. participants have collaborated to create, plan and prepare an enactment. On the other hand, a ready-written script has been presented which the participants then “performed”. With the former, to use the word favored by one of the student-participants of the happening 12, the “agency” of the participants was promoted. With the latter, the people involved subordinated their individuality to the purpose of the enactment – a form of objectification that can be part of happening.[9]Martin Blaszk, Happening in Education – Theoretical issues. Peter Lang, 2017, pp. 84-87. In connection with the happenings mentioned in this text, 2 Suited People 2 Yellow Suitcases, What Where Reactions and The Complete Works, were the result of a process of devising, whereas in Catching Breath Along A Pier, Restricted Sightings and 12, the participants were asked to enact a ready script.

The author would like to thank the participants of 12: Justyna Betańska, Rozalia Ekiert, Aleksandra Knitter, Oliwia Kurlej, Mikołaj Nurzyński, Klaudia Schmidt, Aleksandra Szostek, Mateusz Włostowski and Weronika Żołędziowska. The happening was made possible by their willingness to take on the challenges posed by the enactment as well as their determination to complete it.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Martin Blaszk.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.

Notes

| ↑1 | As part of their studies in the second semester, the students did a 30-hour component that promoted artistic involvement. The title of the component was Creative Involvement Through Happening. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | A considered view of Schlemmer’s research at the Bauhaus is given in: Małgorzata Leyko (ed.), Schlemmer. Kantor. Cricoteka, 2016. It has the additional merit of showing links between the creative experiments of Schlemmer and the Polish artist and theatre director, Tadeusz Kantor. |

| ↑3 | The interpretations were included as reflections in a portfolio which students had to complete in part fulfillment of the component. |

| ↑4 | Henry M. Sayre, The Object of Performance: The American Avant-Garde since 1970. University of Chicago Press, 1989, p. 23. |

| ↑5 | Jerzy Limon, Piąty wymiar teatru. Słowo/obraz terytoria, 2006, p. 131. Additionally, Limon devotes the third chapter of his book to performance art in comparison to theatre. The chapter is titled O prowokacji w teatrze i sztuce – On provocation in the theatre and art (translation MB). |

| ↑6 | The script for the happening stipulated twelve participants to be involved in the enactment, while other participants would be engaged in the documentation. Before the happening, it was apparent there would not be enough people. The happening was enacted with nine participants. |

| ↑7 | A compilation of the playwright’s drama texts: Samuel Beckett, Samuel Beckett. The Complete Dramatic Works. Faber and Faber Limited, 2006 [1986]. |

| ↑8 | Deirdre Heddon and Jane Milling, Devising Performance. Palgrave Macmillan, 2006, p. 3. |

| ↑9 | Martin Blaszk, Happening in Education – Theoretical issues. Peter Lang, 2017, pp. 84-87. |