Fifteen-year-old Rory, a schoolgirl on the adventure of a lifetime, is puzzled. “Why,” she asks, “is there such a difference between boys at school and boys in the wild?” Good question: Rory is in Tromsø, which is north of Norway and pretty far from her home, and she’s just bumped into some Norwegian boys. And they look cool. And they look hot. And suddenly she’s interested. And so is one of them: Andreas. She puts on what she hopes is “a confident but easy-going smile,” and he offers her a drink. She accepts. There’s only one thing she can’t tell him: in her rucksack she has the cremated ashes of her father, and she aims to scatter them at the North Pole.

Tatty Hennessy’s debut play, a one-woman show delivered with great panache by Gemma Barnett, has already been seen at the Arcola, at the 2018 Vault Festival, and on a national tour. Now arriving at the Trafalgar Studio 2, it exploits the intimacy of the venue to explore the piece’s themes of loss and coming of age. When the geography teacher father of Rory—short for Aurora—dies in a car crash, she takes a look at his papers in his desk at home and discovers that his passion for North Pole explorers included a plan to go to the Arctic. Sadly he never made it in life, so Rory decides to take his ashes there. Only one problem: she hasn’t told her Mum.

Running away from home with a passport and her Mum’s credit card, Rory takes the urn holding her father’s ashes to the geographical North Pole as a way of making good the disappointments of his life. Along the way, she talks about his enthusiasm for the cold northern climes and the great explorers of history, such as Shackleton, Franklin, Peary, and Nansen. At the same time, this monologue shares lots of ideas about North Pole exploration. We find out about the five different kinds of pole, from magnetic to geographic, and about Tromsø, its museums and the plight of polar bears in the far north. There are fascinating details about dead bodies in the frozen wastelands and women explorers who have been hidden from history.

We know that the Inuit don’t really have a hundred words for snow, but that doesn’t matter here. The frozen north is not only a real place, which Hennessy visited on a research trip and describes with a nice mixture of wonder and dread, but also a metaphorical place. The land is a cold wilderness which is inhospitable, and Rory’s feelings after the death of her father are on emotional lock-down, so she embarks on a quest that is as much a search for a metaphorical home as it is an earthly journey. The further north she goes the deeper her emotions are explored. The coldness of loss is evoked in beautifully simple language.

At the same time, Rory’s journey is an uncertain mix of fantasy and reality. I wasn’t really convinced that this nice middle-class teen would embark on such an adventure without talking to her mother: at the start of the play they are quite close, and Rory’s jokes about her Mum are the normal frustrations of all teens. She seems too sweet to be a rebel. Yet although the premise of her mission doesn’t feel right, being more of a fantasy than a real event, Hennessy does inject the story with some realistic detail. Rory’s meeting with Andreas, that rapidly becomes intimate, is told with excruciatingly true detail. And the equation of female virginity with virgin territory is metaphorically strong. We are, after all, raping the planet.

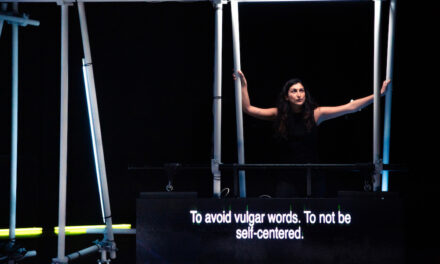

The play’s points about the fate of our Earth, symbolized by the declining condition of the polar bears, are well integrated into the human story as Rory meets a couple of locals that help her achieve her objective. By the time we get to the unexpected ending, there are a couple of genuinely moving moments in Lucy Jane Atkinson’s clear and confident production. The set, by designer Christianna Mason, looks like a cross between old-world geography textbook and a museum exhibition, and Barnett’s performance is wonderfully engaging. Projecting a personality that is sassy, self-aware and self-deprecating, she gives Rory a character that beams with smiles and then suddenly turns serious, a young woman who is both opinionated and sensitive.

Reading the show’s program, with its concerns about climate change and its desire to reinstate women to their rightful place in the history of polar exploration, you can easily applaud the politics behind the project. There’s also a lot of humor in Hennessy’s writing, which has an attractive brightness, even when talking about grim issues such as funerals and grief. Although this is quite a short piece, barely 75 minutes long, there is an epic reach to its ambition. And many of the details of life in a subzero world are memorable. If some passages, about the family for example, or plane crashes, work better than others, there is a warmhearted feel to the show that can thaw any critical chilliness. After this success, I only hope that Hennessy goes on to write more and more.

A Hundred Words For Snow is at Trafalgar Studios until March 30.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Aleks Sierz.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.