American writers don’t get much bigger than David Henry Hwang. The award-winning playwright’s best-known works, which include FOB, M. Butterfly, Yellow Face, and Chinglish, are some of the most acclaimed works in the modern theatrical canon. Indeed, Hwang’s influence on the American dramatic arts has been so profound that a society was established in 2016 for the scholarly examination of his works.

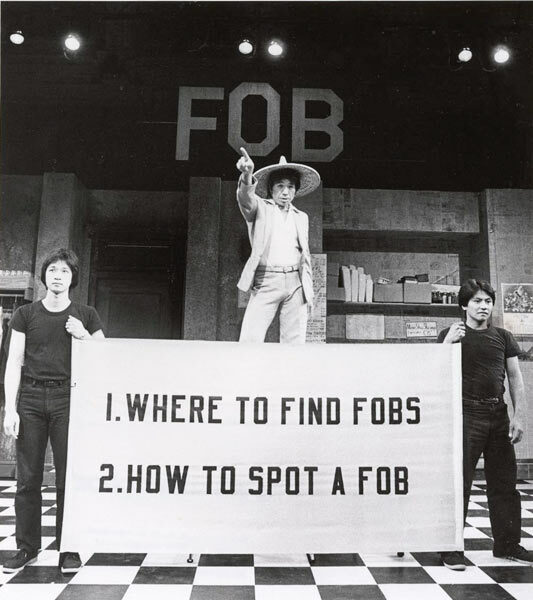

Born in Los Angeles to Chinese immigrant parents, some of Hwang’s works, including 1980’s FOB—an abbreviation of the phrase “fresh off the boat”—and 1981’s The Dance And The Railroad and Family Devotions, explore the nature of Chinese-American identity. Later, his seminal M. Butterfly, based on a love affair between a French diplomat and a Chinese Peking opera singer, won the 1988 Tony Award for Best Play.

Over the years, Hwang has been honored with a host of accolades. He has been nominated for two other Tony Awards, has won three Obie Awards, and is a two-time finalist for the Pulitzer Prize for Drama. Hwang is also America’s most-produced living opera librettist, whose works have been honored with two Grammy Awards. He is currently a writer and consulting producer for the Golden Globe-winning television seriesThe Affair and serves as head of playwriting at Columbia University School of the Arts. Last month, Disney announced it had commissioned Hwang to write Hunchback, a live-action musical adaptation of the Victor Hugo novel, The Hunchback Of Notre-Dame.

Sixth Tone caught up with Hwang on one of his regular visits to Shanghai to discuss the legacy of 1980’s FOB, his Chinese roots, Asian-American identity during the Trump era, and the future of Chinese theatre.

David Henry Hwang speaks onstage at the American Theatre Wing Centennial Gala in New York, Sept. 18, 2017. Jemal Countess/Getty Images/VCG

Sixth Tone: You wrote your first story as a 10-year-old and established yourself by age 22 as a young Chinese-American playwright in probably the most competitive entertainment market of the time. How did you achieve it?

David Henry Hwang: I actually wasn’t particularly interested in writing before I got to college. The sole major writing project I did was as a 10-year-old when I went to the Philippines to record an oral history with my grandmother, which I then adapted into a 90-page “novel” about the history of my family.

When I got to college, I became interested in writing plays, wrote one to be done in the lobby of my dorm my senior year, and this play, FOB, opened 14 months later off-Broadway at New York’s Public Theater.

I credit my early emergence into New York theater to a combination of community activism, chutzpah, luck, and, I suppose, talent. Community activism, in that Asian actors about a year earlier, had protested an incident of “yellowface” casting at The Public, and its founder, Joseph Papp, hired one of the protesters onto his staff to find plays for Asian actors. So, I was the beneficiary of affirmative action.

Sixth Tone: Did FOB represent your ascendance to Broadway or to the theatrical world in a larger context? What message did you try to convey in FOB?

Hwang: FOB wasn’t produced on Broadway, but it represented my emergence on the New York theater scene and as an American playwright since the show received good reviews and won an Obie Award, off-Broadway’s highest honor, for best American play in 1981. The play tells of the conflicts between FOBs and ABCs [American-born Chinese], yet also attempts to forge a theatrical form which felt to me uniquely Asian-American, blending American naturalism with some representation of Chinese opera.

Sixth Tone: What was life like for Chinese-Americans, both so-called FOBs and ABCs, during that time period?

Hwang: In 1980, Chinese-Americans were certainly considered perpetual foreigners to America, even more so than today. In addition, Asians, in general, were regarded as poor, uneducated, and manual laborers—cooks, waiters, laundrymen—an image which has turned 180 degrees in my lifetime.

Sixth Tone: How does that compare with their situation now–prior to and during the Trump era?

Hwang: Now, if anything, the stereotype is that we’re too wealthy and too powerful. However, we are still often regarded as perpetual foreigners, particularly in the Trump era, which seeks to demonize most non-whites as threats, and China in general as the enemy of American dominance. So, in many ways, we are starting to return to a 1960s or ’70s mentality, where Chinese-Americans may be scapegoated as part of a larger hostility toward China.

Sixth Tone: M. Butterfly has received rave reviews and has been your most successful play. What made it so successful?

Hwang: I feel that the show’s success reflected its willingness to confront issues which at that point were still new to Broadway: gender fluidity, the white-supremacist lens of works like [Puccini’s opera] Madame Butterfly, Asian emasculation, and the shifting East-Westpowerbalance, to name a few.

Sixth Tone: What were the difficulties you encountered in entering the theater world?

Hwang: I feel my early, off-Broadway plays—such as FOB—were regarded as somehow less substantial or important than works by white, male playwrights, which were still considered the standard of universality in those days. M. Butterfly changed that, however, and I was suddenly a major American playwright.

Sixth Tone: When did you last visit China? What changes have you personally observed in the country, compared with that time?

Hwang: I was last in China in December 2016. One big difference: I hardly saw anyone smoking this year! Also, conspicuous consumption seems to be down, or at least more subdued.

Sixth Tone: Your father is from Shanghai. What is his story? How did your parents and upbringing affect your career as a writer?

Hwang: My grandfather immigrated to Shanghai from Yancheng[City] in Jiangsu province. Starting by making soap, he became a successful entrepreneur but left China just before the revolution in 1949. My father grew up in Shanghai but rebelled against his father and went away to the U.S. for college. My mother is Fujianese, from a merchant Chinese family that established a successful business in the Philippines. Her grandfather moved the family to the Philippines during WWII to escape the Japanese, which of course proved unsuccessful. My mother went to America to study piano and met my father at the University of Southern California. I suppose this means I come from a legacy of men who didn’t do what their fathers expected them to!

Sixth Tone: How do you see the state of Chinese theater today? How does that relate to foreign models, such as Broadway or the West End, and do you think the Chinese mainland theater industry should look to imitate such models?

Hwang: It seems to me that the biggest challenge for Chinese theater is to cultivate an audience, which would make possible long-running shows. A show that only runs for a few months, tops, fails to generate enough revenue to pay back the investment required to create it. A Chinese Broadway or West End may help to build an audience, but more theaters alone probably will not achieve this goal.

Sixth Tone: There is significant collaboration between the American and Chinese film industries— the largest two in the world. Could the two countries’ theater worlds establish a similar kind of relationship?

Hwang: I think there are already many attempts underway at the moment to create collaborations between Broadway and Chinese theatre. The question is: Will this lead to China being able to create its own musicals that become worldwide hits, or simply open up the Chinese market to more Western product?

Sixth Tone: One of your latest works is Soft Power, named after a concept that has dominated many disciplines in recent years. What does that play tell us about the world today?

Hwang: Soft Power is a play that becomes a musical. It envisions a King And I—like Chinese musical in the future, which utilizes the soft power tools of the form to celebrate how China stepped in to lead the world when America collapsed after the 2016 election.

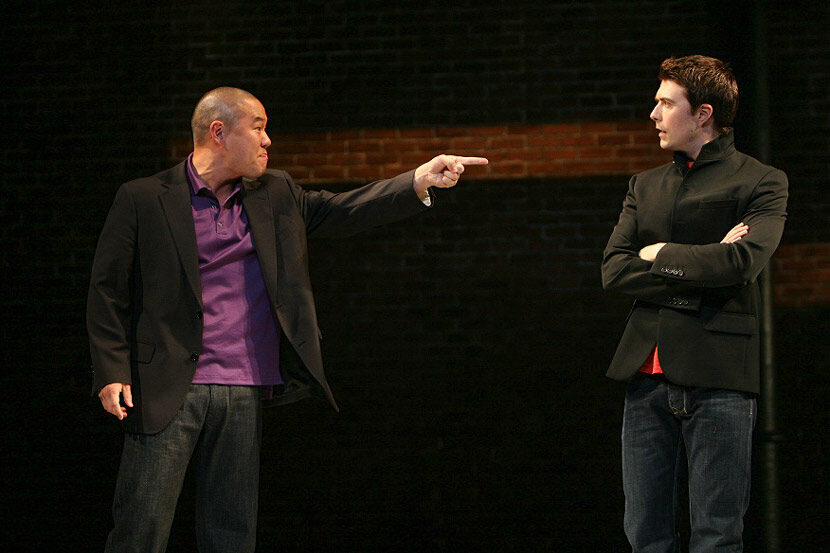

A photo from a production of Yellow Face at The Public Theater in New York, 2007. Courtesy of Michal Daniel

Sixth Tone: You recently said in Shanghai that American soft power has come to an end with Trump’s election to the U.S. presidency. Do you think soft power is limited to political leadership only? American music, for example, still seems highly influential among youngsters here.

Hwang: I don’t believe soft power is limited only to political muscle — witness Britain selling cultural products without a dominant economy or military might. However, I believe the ability of those narratives to reinforce America’s vision of liberal democracy has probably come to an end.

Sixth Tone: What kind of soft power can China’s storytelling, playwriting, and performing arts exert?

Hwang: China has a great capacity to try to advance its vision for the world through its art and culture — which, again, is what Soft Power tries to explore. However, its efforts thus far have been rather ham-fisted and heavy-handed, which is why a small country like South Korea has had more influence on world pop culture than China. The question for me: Are China’s goal to achieve soft power and its top-down, strict content restrictions inherently contradictory?

Sixth Tone: What kinds of Asian or Chinese theatrical techniques should Western theater adopt? Have you used any of these techniques in your own work?

Hwang: I generally have tried to borrow from traditional Chinese theatrical forms, in particular, Chinese opera.

Sixth Tone: What are the fundamental differences between Western and Chinese storytelling?

Hwang: Chinese storytelling tends to be more episodic, whereas the Western method relies on a strong, unified narrative. In that respect, Chinese classics feel more like The Canterbury Tales or Western television pre-cable.

Sixth Tone: How do audiences today compare with those from 20 or 30 years ago? Are there any differences between generations X, Y, and Z? How do they tend to view M. Butterfly or other works of yours?

Hwang: In terms of theater, I think the musical is closer to the heart of American popular culture than at any time since the 1950s. Plays, on the other hand, seem less influential than before—particularly with the rise of quality television—and only enjoy long runs on Broadway when they behave like musicals such as Harry Potter and Warhorse. I believe the digital age, in general, has enhanced the value of all live events, including sporting events, concerts—and theater.

A production photo from the play Chinglish at the Goodman Theatre in Chicago, 2011. Courtesy of Eric Y. Exit

Sixth Tone: Do you think sitcoms are the strongest domain of American screenwriting? Why are they still one of the strongest U.S. exports to Asia and other parts of the world?

Hwang: I don’t believe sitcoms are America’s strongest form of screenwriting. If anything, I would argue that edgy dramas—shows like House of Cards, Breaking Bad, The Sopranos, The Americans, Game of Thrones—represent the best work being done today in American media. Some of this content is controversial, however, in foreign territories, whereas sitcoms tend to be relatively safe and therefore easier to export.

Sixth Tone: How do you view today’s debates over identity—or identity politics, as they’re sometimes known—and their place in theater or other cultural industries?

Hwang: I believe identity issues are more important now than ever. In America, the Trump coalition seeks to use white identity to further marginalize and disempower everyone else in the country. Issues of cultural identity define most of the world’s major conflicts today, from migrants to Brexit, to the Middle East. In China, cultural identity pops up in controversies from Xinjiang, to Tibet, to Hong Kong, and Taiwan. This is the age of identity crisis; for better or worse, culture wars matter, and art necessarily reflects that reality.

This article originally appeared in SixTone on February 27, 2019, and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Mevlut Katik.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.