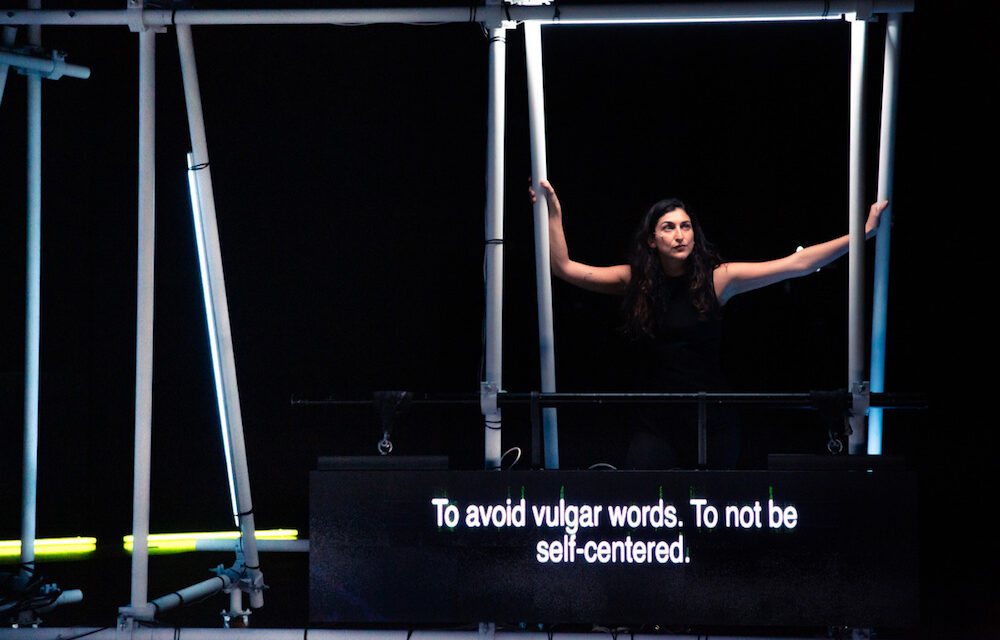

I can give two accounts of Sachli Gholamalizad’s solo performance Let us believe in the beginning of the cold season, which premiered on May 11 at KVS in the frame of KFDA. First one: It is a show by a very virtuosic performer, sliding back and forth between semi-autobiographical storytelling, video interviews of Gholamalizad’s mother, spoken poetry of Forugh Farrokhzad’s verses, and singing; a show that is built on the hyphenations of the performer’s identity across Iran and Belgium, with the modular light and screen fixture as a material aid for, as well as a metaphor of, such division of sense of belonging. This account is not necessarily untrue, and it wouldn’t spoil the work’s pleasure for the potential viewers. The other story I might tell is less pleasant, and precisely about the problem of pleasure.

A beautiful pair of eyes, a set of red lips, all framed with gentle wrinkles around. We hear an off-screen, younger female voice, asking about the childhood stories this face used to tell to the unseen interlocutor. The first name that pops up is all too familiar, 1001 Nights, of course. There are others with more generic titles, many of which grouped under the same stock opening in Farsi folktales: “Yeki bud, yeki nabud” [There was one, and there wasn’t one]. Gholamalizad enters inside the cage-like structure on stage, to face the cameras installed in it. With their live feed to the screens attached to the structure, we see her eyes and lips, hinting at the genetic connection with the previous face, which soon turns out to belong to her mother. Gholamalizad dwells on the meaning of this opening line, and moves on to narrate The Conference of Birds, the 12th-century Persian epic that the audience is also likely to be acquainted with, either by its wide literary acclaim in the West since the late 19th century or through Peter Brook’s stage adaptation in the 1970s. She announces the spiritual message of this extended Sufi parable from the outset: “Every creature has to find what their life means.” The performance then cuts back to the video interview of Gholamalizad’s mother, visiting the linguistic struggles this first-generation immigrant woman still experiences.

The whole performance is ostensibly built on this problem of inhabiting a language, and of finding authentic self-expression. Forugh’s poems are evoked as part of this second concern, especially as they manifest feminine desire in contradiction to the social conventions of Iran. Gholamalizad performs excerpts from Let us Believe… in English translation, with some verses sung in Farsi, accompanied with original music by Jan De Vroede. Within the first 15 minutes of the performance, we are given three literary sources that a Western audience might already know of due to their culturally representative status and global recognition, if not by a meaningful engagement, and be quite sympathetic listeners by virtue of this familiarity. In that sense, the selection of these texts feels quite safe, not to mention the risk of representing Iranian literature through its own canonic and “timeless” examples.

The rest of the performance goes on to cut back and forth between Gholamalizad narrating us the broad strokes of the birds’ journey to self-enlightenment, performing selected verses from Forugh with an ethereal voice and sensual dances, expressing her frustration in a self-interview on video about not feeling fully accepted in Belgium or at home in Dutch language, plus a bit more of her mother comparing her experience with language in Iran and in Belgium. Through it all, Gholamalizad establishes an erotic relationship with the audience, not only as an effect of the intimacy of her deep and breathy voice, but also framed with the shades of fluorescent light as she looks directly at the live feed camera, or singing downstage and flirting with the audience as her slender figure sways by the microphone stand. Eyes, lips, a dancing silhouette against the strobe lights and smoke to an electronic beat: this is the picture Gholamalizad repeatedly shows us, never undoing its self-assured sleekness, or questioning its purchase with the Orientalist gaze.

This relationship never topples down, which implies that she is enjoying, or even unwittingly employing, that gaze herself. At best, this renders the performance a lost opportunity to reveal the very mechanisms of how the politics of multiculturalism and integration might fail in day to day encounters. At worst? The use of Forugh’s work in the performance feels instrumentalized. Forugh’s poetic sensuality was a protest with real stakes against the veneer of modesty in pre-Revolutionary Iran, intermixed with her struggles between public slut-shaming, mental breakdown, and temporary self-exile. Gholamalizad’s feeling of displacement in Belgium seems to be an overstretch in comparison, the expression of which never lands on a concrete example or moment of shared vulnerability (unlike her mother, whom we watch struggling to repeat Dutch words after her daughter, incompetently, with a wide smile of embarrassment). If Gholamalizad is in fact not telling a story, thus refuses sentiments of pity or denies us a candid revealing of her authenticity, that decision is not translated into a performatively compelling rupture, either, and the piece falls into the trap it sets. The impossibility of recognition across cultural and linguistic divisions is perhaps implied, but aesthetically and libidinally the flow remains uninterrupted, leaving us with a hazy and absorbed mystification of what it means to be a woman in the diaspora with a scar on her tongue.

This article first appeared in Etcetera and has been reposted with permission. Read the original article.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Eylül Fidan Akıncı.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.