Godot in Wuhan was a special session at the Twelfth Between.Pomiędzy Festival conducted within the framework of the Beckett seminar in Gdańsk. The University of Gdańsk Samuel Beckett Seminars have been organized every year since 2010 by the Beckett Research Group in Gdańsk, led by Tomasz Wiśniewski. They have been attended by scholars and artists from various parts of the world and have resulted in several publications, film documentaries, workshops/laboratories, and theatre productions. The following transcript records the online discussion between Professor Peng Tao (Central Academy of Drama, Beijing), Wang Chong (Théâtre du Rêve Expérimental, Beijing) and Katarzyna Kręglewska, and Tomasz Wiśniewski, both from the University of Gdańsk, Poland.

Tomasz Wiśniewski: The Twelfth Between.Pomiędzy Festival and the University of Gdańsk’s Samuel Beckett Seminar 2021 is opening in an extraordinary way and, in fact, a day before the proper festival begins. We are honored to start with a special panel on Beckett in Wuhan in China, and I am convinced the conversation will resonate throughout the festival week.

Peng Tao from the Central Academy of Drama in Beijing will introduce the general context of the zoom production of Waiting of Godot that happened a year ago. Then, Wang Chong from Théâtre du Rêve Expérimental, the director of this extraordinary event, will speak. After this, there will be time for questions from Dr. Katarzyna Kreglewska and me.

Peng Tao: First of all, I want to thank Professor Wiśniewski and Dr. Kręglewska for inviting me to attend this wonderful seminar. I want to introduce the translation and the production of Beckett’s dramas in China. The reception of Beckett’s dramas began with their introduction to China and their translation. Beckett’s drama in China experienced a period of rejection, critical reception, and finally overall acceptance.

The first Beckett translation in China was Waiting for Godot in 1965, when it was presented as an example of bourgeois decadent literature and it was criticized at that time. Since the 1980s, with China’s reform and opening, Beckett’s plays have gradually been accepted in China and even incorporated into Chinese literature textbooks for high schools and universities. Since the 21st century, the translation of Beckett and his works has reached a climax. In 2016, to commemorate the 110th anniversary of Beckett’s birth, Hunan Literature and Art Publishing House published Beckett’s complete works in 22 volumes.

Waiting for Godot is Beckett’s most frequently performed work in mainland China with some 17 productions since 1966. Here, I would like to mention two important versions. One is Meng Jinghui’s version performed at the Central Academy of Drama in 1991, and the other is Lin Zhaohua’s version produced in April 1998.

In Meng Jinghui’s version, Beckett’s two-act play was brought to the stage in order to express the dissatisfaction and traumatization of a younger generation. Beckett’s metaphysical musings on the meaninglessness of human existence are transformed into a disturbing allegory of the pent-up anger and rage of youth in the 1990s. As Meng Jinghui said, “What we are presenting is not an imitation of a Western play, but a reflection of the current era. I have expressed the depression, anger and contradictions of the young people at that time.”

Director Lin Zhaohua put Beckett’s Waiting for Godot together with Chekhov’s Three Sisters in a collage in 1998. For Lin Zhaohua, the theme of waiting in Chekhov’s Three Sisters is a classical waiting, a waiting for a better future, while the waiting in Beckett’s Waiting for Godot is a modern waiting, a waiting after losing faith and a sense of ultimate value.

The most interesting production is Wang Chong’s online Waiting for Godot, which was produced in April 2020. This work was broadcast on the internet for two consecutive nights: on April 5th and April 6th last year. The audience was able to watch it for free on the internet. According to the official statistics, there were 180,000 people watching the show on the first day, and the number on the second day reached 120,000.

First of all, I want to mention the background of the show: on 23rd January 2020, Wuhan declared a “lockdown.” And the lockdown lasted 76 days. On April 8th, Wuhan announced the “unlock.” So, the online play Waiting for Godot was staged on the internet just three days before Wuhan was released.

The cast and the production team of Waiting for Godot came from four different cities: Beijing, Datong, Guangzhou, and Wuhan. After more than two months of online rehearsals, they finally chose to release the performance before the “unlock” in Wuhan. The wasteland in Beckett’s play becomes living rooms in the home of the two leading actors in isolation. Vladimir and Estragon, two vagabonds, are portrayed as a couple of lovers who are isolated in different cities by the epidemic and who can only maintain their relationship through mobile phone videos.

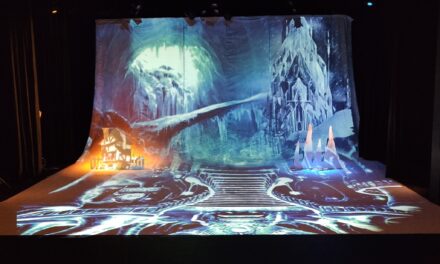

Waiting for Godot screenshot. PC: Wang Chong.

As the performance begins, Estragon is trying to untie the laces of her high heels. At the same time, Vladimir picks up a glass of water and drinks. Waiting for Godot has realistic content in the play: people in quarantine are waiting for the epidemic to pass, waiting for the city to be “unsealed.” Wang Chong brought Beckett’s play to the present situation: the boredom of waiting in the play is a real reference to the boredom and loneliness of the people who are quarantined during the epidemic. The question “Will Godot come?” also has a realistic context. When will the epidemic end? When will life return to normal? The audience’s smartphone screens are just like a mirror: we see ourselves living in isolation, and we see the daily life of killing time with smartphones in boredom and loneliness.

Pozzo is presented as a boss in shiny clothes and Lucky is his employee. The background and elements of COVID-19 are deliberately emphasized by the director: in the first act, when Pozzo coughs at a certain moment, Vladimir and Estragon immediately put on their masks in fear.

In the second act, their power relationship is switched: Pozzo is dying in a hospital bed with COVID-19, while Lucky drives his car through the streets of Wuhan at night. The scene is a metaphor for a post-epidemic revolution: Lucky has been set free from being enslaved, and Pozzo, the former dictator, is dying. The performance reached its climax at this moment, and then, once again, became a boring waiting. . . . Wang Chong’s Waiting for Godot is a response to the reality of COVID-19, especially the daily lives of people living in isolation.

To some extent, COVID-19 is a blow to globalization, to our lives. The rise of racism and authoritarianism, economic and political conflicts have forced us to reflect on what the potential global crisis in the run-up to COVID-19 really means. In my opinion, Wang Chong’s Waiting for Godot is a serious work that reflects the crisis of our life and makes us think about the meaning and value of our existence.

Wiśniewski: Thank you so much for this short introduction to the status of Beckett in China, in general, and to the context of Waiting for Godot by Wang Chong, in particular. At this point, we may turn to the director himself. Wang Chong, may I ask you for your introductory remarks?

Wang Chong: I’m very honored to be part of this seminar and thanks so much, Professor Pang Tao, for your kind words. Of course, I’ve seen the video recordings of the two important Chinese productions of Waiting for Godot from the 1990s, but I strongly believe in Peter Brook’s notion of the Immediate Theater. It was 2020, everything has changed in our world, so it’s our responsibility to provide our own version. I was very much struck by the epidemic news. It wasn’t a pandemic then, in February 2020. I was struck by the news. I read the news every day, even though I was in Australia. I was struck emotionally, then I couldn’t get my mind off these bad feelings and speculations over the situation in Wuhan. That’s where the concept stemmed from, in February. Very quickly we assembled the team; we worked with Guangzhou Opera House to put everything together. Then we started rehearsals in March and we put on a show with a performer whom I’ve never met, Li Boyang from Wuhan. There’s definitely this vibe. Because during that time nobody could do any theater in China, not to mention in Wuhan. Theatre was basically dead in March and April. Then, I really wanted to ask this question: why couldn’t we do theater, especially in Wuhan? By then, of course, I had discovered this fabulous device, Zoom, which is globally popular. I started to use it in 2019 and really wanted to do something with it. I didn’t know what, but by March 2020 I knew that I should put a zoom-based Waiting for Godot and Wuhan together to create an Immediate Theater piece.

There’s one thing I really want to point out. The performance was performed live and live-streamed for two nights. The first night was Act One and the second night was Act Two, so that we could create this feeling of waiting one day after another, and that waiting could go on forever, even though Wuhan was “unlocked ” one day after our performance finished. So that’s the context of everything from last year.

After we finished that piece in April, I published online an Online Theater Manifesto, because I saw after this process that online theater could be something for the future. Not only for 2020, not only for the pandemic; it could open up new gates for theater-makers for the future. And another very important thing that I realized in the process is that Beckett is truly timeless. We found so many things that were incredibly relevant to the pandemic in Wuhan. For example, in Waiting for Godot there are references to pneumonia, there are references such as:

ESTRAGON: We’ve no rights any more?

VLADIMIR: You’d make me laugh if it wasn’t prohibited.

ESTRAGON: We’ve lost our rights?

VLADIMIR: We got rid of them.

And there are also references to people, people’s relationships, people breaking up, and people in isolation. So, I could perfectly imagine – 200 years from now Beckett will still be performed and people might perform Waiting for Godot with one person in a space station, the other on a planet. That could be the future of human theater and the future of Beckett. That’s basically what I have to say for now. I would like to open up the conversation and receive questions.

Wiśniewski: Thank you so much, Chong and Tao, for this initial introduction, and thank you so much for making us aware of the global dimension of Beckett. Also, Chong, you talked about the need which we have probably experienced so deeply and profoundly recently during the pandemic, the depth of Beckett’s work and its accuracy for these days. Just before the lockdown here in Poland, I went to London to watch Endgame at The Old Vic, and later on, just a week later, when I was back here in Gdańsk, in Sopot, I suddenly realized how much the experience which is presented in the play is an experience that we all have now: the experience of excessive restrictions, of the impossibility of leaving the four walls of our flats, of a determining of everyday actions. You hinted at these aspects also in your introduction.

To read PART 2 of the interview, click here.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Tomasz Wiśniewski and Katarzyna Kręglewska.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.