The COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown regulations in many countries across the globe saw people turning to the arts and creative sectors for entertainment, connection and to respond to the unknown. Yet, the cultural and creative industries sector (CCI) is undoubtedly one of the sectors that have been hit the hardest by the COVID-19 pandemic. UNESCO called the situation a “cultural emergency” on a global scale.

The performing arts and celebrations domain of the South African creative industries is severely impacted by the national lockdown. The lockdown regulations meant that the jobs many producers, directors, choreographers, musicians, performing artists, stage crew and technicians had lined up into the second half of 2020, in effect disappeared.

Katlego Chale, André du Preez and Shamiga Makaku in Little Red Riding Hood and the Big Bad Metaphors (2019). Directed by Khutjo Green. Set and lighting design by Wilhelm Disbergen. Costume design by Nomzamo Maseko. Play by Mike van Graan for UP Drama Department.

Theatres and entertainment venues closed down during South Africa’s lockdown level 5. Arts and music festivals were canceled or postponed. Amendments to allow theatres to operate as studios for recording or live-streaming productions with small casts and were gazetted in May. The audio-visual and interactive media domain could resume operations within specified parameters. In lockdown level 3, theatres can partially operate again, but with limited capacity and with social distancing measures in place. There are limitations on the number of performers, stage crew, front of house staff, cleaners, and technicians that may work on a show. Screening protocols need to be in place and the multiple spaces in a theatre complex will likely need to be sanitized after every rehearsal and every show. All of this makes it nearly impossible for theatres to remain financially viable and some theatres already indicated that they will only reopen their doors at some time in 2021. This, of course, comes at the cost of retrenchments and job reductions. It not only impacts those working in and for the theatre, but also those working in other areas that provide services to the theatres, such as food and beverage, providers of specialized equipment, printing, etc. On 15 August, President Rapamphosa announced that South Africa will move to lockdown level 2. The restrictions on group gatherings, however, remain in place.

Whilst many performing artists work across a number of domains and so may have diversified their employment opportunities, the ‘health’ of the employment opportunities in almost the entire CCI sector is in jeopardy. Why should we be concerned about that?

Nthabiseng Masethla and Kirsten Dickenson in The Snow Queen. Photo: Nicole Barnes.

The social and cultural contribution of the CCI sector is well documented. Its economic contribution less so. A 2018 mapping study of the South African Cultural Observatory (SACO) showed that the CCIs directly contributed 1.7% to South Africa’s economy in that year. Considering that agriculture contributed 2.4% in 2018 and that 7% (1.136 million formal and informal jobs) of all the jobs in South Africa (SACO 2020:8) are related to the CCIs, the importance of the creative economy should not be underestimated. An early assessment during 30 March-4 May by the South African Cultural Observer indicated that what was in effect a shutdown of the sector, was then estimated to reduce South Africa’s GDP by R R99,7 billion (direct and indirect impact) in 2020 (SACO 2020:53). The SACO (2020:49) estimated that the impact (excluding the induced impact) on the total output of the performing arts and celebrations domain will be affected by –R6.4 billion with a drop in GDP of -R2, 8 billion and a drop in intermediary imports of –R583 million. This is why the show must go on.

Whilst there were already indications of demand for content creation and projects for broadcast TV, online platforms, and arts festivals beyond level 5 (and whilst some activities could continue online), those working in these domains had to re-consider and re-conceptualize their means of operation in the domain.

For the performing arts in specific, those working in the domain had to reimagine the very nature of the domain.

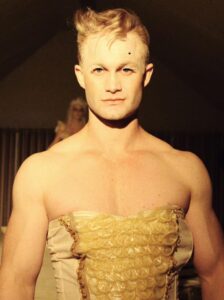

Émil Haarhoff in Ba(R)ok (2018).Directed by Johan van der Merwe and Marié-Heleen Coetzee. Costume design by Leonard De Villiers.

The performing arts are vulnerable because of the large proportion of freelance engagement and face-to-face production. Further, much of the performing arts rely on live engagement with groups of people in a central space. Performers are in close proximity to each other in sharing the stage or performance space. Backstage areas of theatres are shared by actors and crew members who come into close contact with each other. Dressers, make-up artists, props managers, stagehands and stage managers all work together to create the magic that is live performance. Some modes of a live performance may require one-on-one engagement with an audience member or necessitate a transgression of the boundary between audiences and performers. Theatre and performance used in corporate and industrial contexts often operate under similar conditions. Sound and lighting booths are generally small, enclosed spaces in which social distancing is almost impossible.

The performing arts is a practice and product of interrelations and interactions. Embodied engagements and visceral exchanges that foreground the ‘felt’ and the sensory are central to the performing arts – developing a kind of kinesthetic resonance that helps to find connections and layer the ways in which we critically engage with processes of ‘worlding’ and the co-construction of meanings or knowledge(s) in a shared space. In training for the performing arts, embodied engagements fuse with bodies of knowledge and practice so that it (in a sense) becomes the practice and the knowledge.

Musa Mngadi in The Snow Queen.In training for the performing arts domain, embodied engagements fuse with bodies of knowledge and practice so that it (in a sense) becomes the practice and the knowledge.

The kind of attention we pay to theatre works and the kind of attention we pay to online viewing content is different. Whether watching a performance or performing, those who share the space are not just in space, their interrelationship shapes the shared space This shaping of shared space and associated embodied exchanges are at the heart of the challenge to reimagine the performing arts in the context of COVID-19.

Theatres locally and abroad make some pre-recorded content available online at no charge or through paid ticketing. It is apparent in recorded performances, no matter how well it is done or whether it was filmed with multiple cameras or with the idea of online distribution or screening in cinemas, it remains a live show that was recorded. The ‘languages’ of theatre and film and digital media are different. So is the positioning of the audience and experiences of immersion in each medium. Augmented performances, mixed reality works, and works using virtual reality have been around for some time and are developing interesting languages of their own. Such performances still require some bodied interaction and/or some form of shared physical space between audiences and performers.

Marina Botha-Spies in Ba(R)ok (2018).

During lockdown level 5, many local artists present monologues, solo dances, or spoken word art on videocasts on social media, posting recordings on YouTube or by live-streaming their work. Writers and actors created live-streamed new works. Digital media artists collaborated with performing artists to develop modes of performance more suitable for online viewing. Small scale online festivals popped up. Artists and institutions tried (and is still trying to) transpose what is essentially a communal, live, and embodied engagement, to a cellphone or computer screen. The National Arts Festival (NAF) took the brave step in April to move South Africa’s oldest and biggest arts festival entirely online. Between Zoom engagements, video-documentaries of past live performances, audio-drama, pre-recorded show footage, screen dance, hints of gaming, and fusions of theatre, dance, and creative digital arts, local and international artists showed their mettle. At the time of writing, attendance figures, the efficacy, and the financial impact of this venture are still to be established.

The innovations demonstrated not only at the NAF, but in many other projects opens up broader understandings of what theatre might ‘be’. Yet, the need for contact, engaging with somatic modes of attention and communal experiences in a shared space persists.

Considering that we do not know when the virus will become a manageable disease, or whether we can expect similar pandemics in our lifetime, the show cannot go on as it did before the COVID-19 pandemic. The South African Government’s haphazard engagement with the intricacies of employment in the performing arts domain over many years saw a large number of artists unable to claim relief or unemployment benefits. The deployment of the government’s artist relief fund seems to be as haphazard and lack-luster as its engagement with the performing arts.

A long-term strategy and the political will to secure livelihoods and the health of the performing arts and celebrations domain – and the CCI’s as a whole – should stand central to visioning the future post-COVID-19.

André du Preez, Bongiwe Ngidi, Bethan Martel, Kukhanya Simelane, Katlego Chale and Sinalo Mkhize in Little Red Riding Hood and the Big Bad metaphors. Photo: Mark Wessels.

What does the future of theatre hold? It seems likely that self-taping may become the norm for auditions and pre-castings, with face-to-face casting reserved for the final rounds of auditions. Training may lean towards small-group interaction and augmented and mixes-reality work. Ticket sales may move entirely online to minimize personal contact in theatre and entertainment venues. Immersive and one-on-one theatre may move out of theatres and bespoke performance venues to create unique modes of immersion for online performance. Live art, performance art, and site-specific performances may become more installation-like.

The performing arts may explore the social production of space or comment on the relational construction of space by experimenting with proxemics. Participatory theatre may shift form to use transmedia storytelling as a participatory device, rather than only physical, face-to-face participation. Technologies and techniques that better suit the language of theatre may be developed to enhance the experience of watching pre-recorded content. Technologies that will enable synchronous performer-audience engagement in mixed reality and augmented performances may become readily available in an online environment. Perhaps theatres and entertainment venues will offer programming options to create malleable engagement with the work they put on, by offering diverse viewing experiences on multiple platforms. Theatres may offer simultaneous, parallel viewing options – live and live-streaming – that may also become on offer as recorded shows. Seeing that smart masks are already available, mask technology may improve to allow artists more vocal expression and nuance, and audiences a better view of performers’ facial expressions! PPE technology may become more sophisticated to become integral to costume design and to allow for closer proximity. Perhaps theatre architecture will be reimagined to allow for bespoke seating or viewing booths at a theatre’s full capacity. Perhaps smart seats will become available.

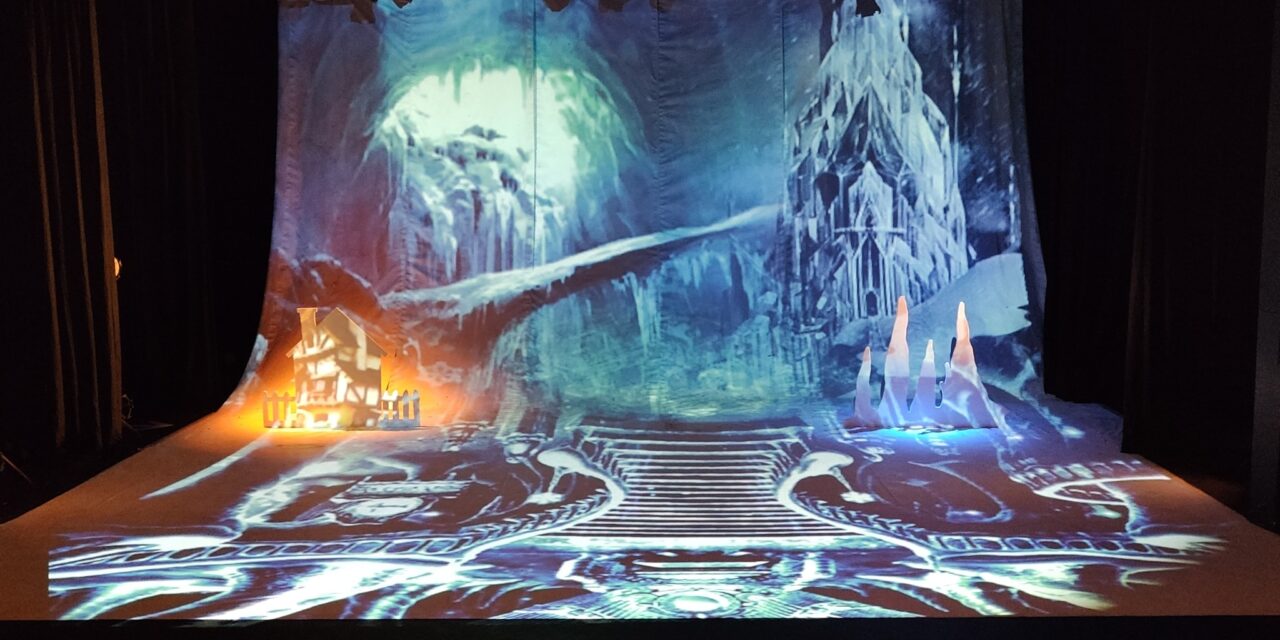

Wilhelm Disbergen’s design for The Snow Queen with Green Hippo’s Hippotizer™.

The history books show us that theatres have been closed due to pandemics before. Beyond closure, the show went on. Whilst the theatres and entertainment venues will likely need to be sanitized for a long time to come, the programming and the content of the work presented in them certainly should not be. Perhaps we will better appreciate the kinesthetic resonance felt when sharing a space with many other bodies in a world where the pandemic is contained, now that we have experienced what it feels like to remain apart. The show will go on.

[A shorter version of this article, Theatre in the time of COVID-19 was first published in The Daily Maverick on 7 August 2020]

References

South African Cultural Observatory. 2020. An early assessment of the impact of the Covid-19 crisis on the cultural and creative industries in South Africa. Online. [Available] https://www.southafricanculturalobservatory.org.za/event/sa-cultural-observatory-releases-report-on-the-impact-of-covid-19-on-cultural-and-creative-industries

UNESCO. 2020. Resiliart: resilient artists and creativity beyond crisis. Online. [Available] https://en.unesco.org/news/resiliart-artists-and-creativity-beyond-crisis

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Marié-Heleen Coetzee.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.