This is PART 2 of the interview. To read PART 1, click here.

Wiśniewski: When I watched your adaptation of Waiting for Godot, I was struck by how mundane activities were globalized in the opening of your performance. Because I don’t know any Chinese, I didn’t follow the verbal dimension, but for this reason I could focus even more on the visual dimension, and I was struck by how much the experience that your actors went through was also my experience. We had Waiting for Godot not somewhere on the road by a tree, but you achieved the pajama intimacy of an urban flat, which was an everyday situation that was experienced last year by everyone, I think, all around the globe.

My first question is about this adaptation, about this movement from the text into the reality around you and your actors. How much, do you think, it enriches your reading of Beckett and how much does it enrich the relevance of this work for a medium which is certainly not a Beckettian medium – for zoom?

Wang: It’s certainly a great question. You know, the experience is there for everybody, not only for me and the cast and the production team, but also for the audience. This is something unprecedented. Previously Chinese people would have to imagine what European people look like and what European homeless people would do with their shoes. Chinese theatre-makers and the audience would have to imagine those things collectively in order to make sense of Beckett. But in our case, everybody had experienced the epidemic, the lockdown, the self-quarantine or quarantine to some degree, so we really had some common ground with the audience. So, I would say Waiting for Godot was never that clear, was never that approachable and understandable to Chinese folks. While creating our version, we would have to, sort of, forget what the stage directions are, in order to make sense of the living spaces of the performers. We used real living spaces of the performers except we rented two cars in order to have street scenes, in order to have the Yellow Crane Tower, a landscape in Wuhan during the night, but we really transformed everything from daily to Beckett. So this is something that’s transformative, theatrical, and magical in a way.

Wiśniewski: If I may follow up with this a bit. I was struck by the visual side of the performance, basic props in particular. It’s fascinating to see a pile of female shoes at the beginning in a situation that seems, initially quite global. Later on, when we have a drive through the night streets of Wuhan, it’s striking how much the city is explored. My attention was caught also by the tiny little artificial tree – a play tree – in the bed later on in the room. All these details were remarkable for anyone familiar with the Beckett text.

We cannot forget about the iconic image of the clock with the constancy of the hour throughout, as if it was an eternal “five past ten.” In one form or another, it was visible on the screen all the time, written in Arabic numerals among Chinese inscriptions which were going over the screen, or on the mobile phone when one of the characters is speaking. Five past ten. I would appreciate your explanation of this detail. Can you also, more generally, discuss a little bit those props which were taken from the Beckett text? And those which were certainly not taken from Beckett, but were very much part of the home situations? I mean here, in particular, the aquarium with fish, this wonderful scene where actors are speaking on the phone, standing by two different aquariums.

Wang: It’s another very good question. Right, definitely, the biggest question that we had to answer was what is the tree in the online Waiting for Godot or the 2.0 version. What is the tree? We didn’t have an answer for that when starting rehearsals, but gradually we found that in order to establish the relationship between the couple we’ll have to have little things in their lives that they might keep just to remind themselves that they are a couple. Very little things like the rings, the tiny trees. The tiny trees could be some sort of souvenir that they both got, so that in different hometowns and different homes, they still keep that. So when they miss each other they hold it in order to, you know, think about the other. So, we tried to establish all those little details in the life of the couple.

And by the way, in March and April, many families in China were still in the Spring Festival mode. You know, the Spring Festival in China is something like Christmas in the West. People would go back to their hometowns to visit parents, to have family gatherings, and then the epidemic hit. For this reason, Chinese people are stuck in their hometowns, not able to go back to big cities, to meet their partners, so without changing or adding words, of course, all these elements should be seen visually. Thanks to the developed internet shopping and delivery systems in China, we were able to get everything delivered fairly fast in order to make the show. But in terms of the fish tanks, they happened to be already there, in the performers’ homes. Then I thought, okay, we had to put these two things together in order to have a stronger visual tie between the couple, so that, you know, these homeless characters in the original script would become homebound characters in our scenario, without changing a word, of course.

Wiśniewski: The metaphor of the aquarium scene worked quite well. Before your turn, Katarzyna, may I add one question about the various methods of streaming that you used. That’s quite interesting, especially because you said something I wasn’t aware of. The zoom performance was streamed live, when it was presented to the general public. How did that work? Any surprises? Any additional challenges? What about another striking visual image of your performance: the night drive through Wuhan?

Wang: Thank you for the compliment. As you all know theater is always very much restricted by limited resources because we have limited time, limited space, limited human bodies, and limited props in theater buildings – and the same is true in virtual theater. My definition of online theater would be: it has to be performed live and live-streamed. Otherwise, it should be called something else: video art or film.

Our piece was performed live and live-streamed and it was really difficult, to be honest, because you have to, you know, hide things that you don’t want to show, you have to choreograph all the actors’ movements especially when they had to be cameramen themselves. All the performers would have to work with their hands to move the cameras around in order to make sense visually, in order to have a steady and fluent flow of the show. We actually started working on live video-based theater in 2011, so we had already nine years of experience. But this time it’s on zoom, it’s slightly different, and of course, you will have to time everything, you will have to do everything again and again in order to make everything match and meet.

For example, that Wuhan street drive part. In that scene, we had to time it. We had to show the lighting of the Yellow Crane Tower in Wuhan at night. Luckily, we started the performance at 8 pm so it was okay, barely. Then we had to measure the distance and the time and then the driver/performer had to drive the car at exactly estimated speed in order to pass that landscape place at the right moment because there was also music going on and three other performers performing, so everything had to be timed.

Katarzyna Kręglewska: For a person that lives in Gdańsk in Poland, the basic images of Wuhan were those connected with the outbreak of the pandemic. You know, we saw some of the images broadcast on the news, but for us, if I may speak not only for myself but for people living here, at the beginning it looked like something really far away and not concerning us. We were shocked, of course, it was something really hard to handle, but it looked somehow as if it wasn’t connected with us. But in April, when you had your premiere, we were already locked down as well. Lockdown in Poland began in March, in the first half of March.

Wang: You mean, in 2020? You were locked down?

Kręglewska: Yes.

Wang: Wow, I didn’t know that.

Kręglewska: Yes, it was the 11th of March as far as I remember. Those images from the news from the streets of Wuhan, and from the hospitals, stayed with me. And watching your performance is an opportunity to see something really valuable. I mean, to see this experience filtered by real people, by artists, and by your sensitivity. I appreciate that a lot.

This performance was streamed for nearly 300,000 people and I would like you to tell us something more about the reactions from the audience. Were there any? And the other part of the question: how much of this response of the audience was rooted in the recognition of Beckett, who, as Peng Tao has mentioned, was already known in China, and how much was about the present situation, and the experience of the pandemic?

Wang: First, I’m very happy that we had such a big audience. We had 290,000 people as an audience in total for Act One and Act Two, so you can say the half is the average who watched the whole show. We cooperated with this giant company that created WeChat – Tencent. We worked with Tencent Arts to live-stream the performance and they have backstage data that we can look at. I was very glad to see that most of the 290,000 audience were very young people who were born in the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s. They were very young people. Beckett has been, for years, a part of our high-school textbooks, so everybody reads an excerpt of Waiting for Godot in a literature class in high school. It’s a really well-known piece and the reception of our performance has to do with that.

Some young people simply said that the waiting is so boring, the show is boring, so probably this group just didn’t get it. Many others said: this is a Beckett that I can understand, or this is a Beckett that is very relevant. So you heard very different opinions, and since the number of audience was huge, you got a debate, but interestingly, the debate has been focusing on my concept of online theater. You know, people in theater circles here are mostly conservative, and people have been debating on one issue: is this theater? Is it really a live performed and live-streamed show or is it a recording? Luckily, in Act Two we had a technical issue sort of revealing the ugly interface of the computer system and backstage software, so one could say: okay, this must be a mistake and must have been live-streamed. And, of course, people have been debating on what online theater is and what theater could be. Is this still theater, or is it something like TV arts or film arts? It’s interesting. It’s interesting in the sense that it’s provocative. We never had so many people debating these issues. I always wanted to do virtual theater and online theater. Waiting for Godot in April 2020 gave me this opportunity. I could have done it in 2019, for example, but the reception and the debate wouldn’t be so big.

Kręglewska: At the end, can you tell us a little about your next production – Plague 2.0, inspired by Albert Camus?

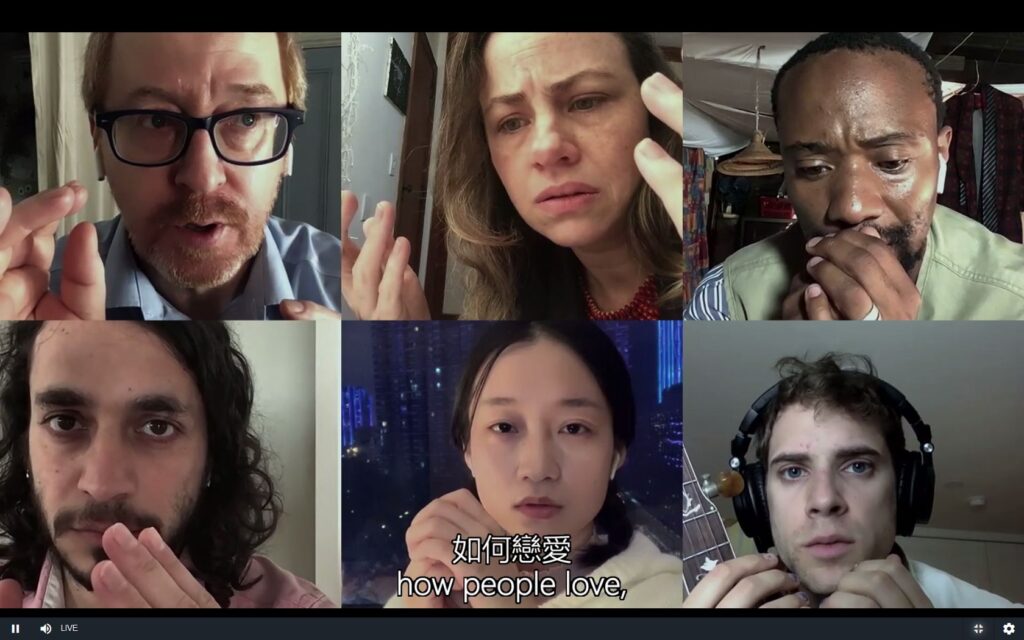

Wang: It was commissioned by the Hong Kong Arts Festival and we did it in March 2021. We had eight live performances in March, and what’s amazing is that in this performance we managed to have six performers working from six different countries including China, America, Brazil, South Africa, the UK, and Lebanon, plus we had a dramaturg and a set designer working from Australia, and the technical team were in Hong Kong. So, we managed to have a cast from six countries and a team from six continents. Of course, it was all deliberate.

We tried to stage a real pandemic and we tried to discuss issues relating to this pandemic in the setting of the play, so that was something very exciting. It was performed live and live-streamed, and the video-recording will be streamed in late May by the Hong Kong Arts Festival. We definitely further developed the language we had already worked on in Waiting for Godot, but in terms of logistics, it’s harder because you have to work with different time zones and, of course, the point is to show different time zones visually in order for it to make sense.

You see very different cities. For example in Wuhan you see glass LED buildings in the back, in South Africa, you see a very roughly built shack, and in Brazil, you see the Jesus Christ statue in sunlight. So you see very different things globally. Yet there is one thing in common: everybody is dealing with the plague as if they were in one town, as is suggested by the script. Then, what is this town? Obviously, it’s the globe. It’s our world, our current world.

The Plague. Dir. Wang Chong. Photo provided by Wang Chong.

Wiśniewski: Which gives a new dimension to the title to the main theme of the Between.Pomiędzy festival that we had last year. It was Kosmopolis, and I think you achieved something like a theatrical cosmopolis in your theatrical production of the plague that you just described. I would like to thank you, Tao Peng, and I would like to thank you, Wong Chong, for this conversation. I’m convinced it will raise questions among our colleagues from the academic world and among practitioners of theatre who are gathered in this seminar and who have experienced, well, similar challenges, when trying to incorporate Beckett into virtual reality.

This zoom conversation was recorded on 9th May 2021 as part of the University of Gdańsk Samuel Beckett Seminar 2021.

Transcript: Karolina Balde.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Tomasz Wiśniewski and Katarzyna Kręglewska.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.