Cazimir Liske, an American actor at the Praktika Theatre, talks about Russia’s literary culture, his experience with the country’s bureaucracy and his work abroad.

American actor Cazimir Liske of the Moscow Praktika Theatre tells Moskovskie Novosti about the difference between theatrical life in Moscow and London, talks about his favorite places in Moscow, and what might make him leave his job in Russia.

I was studying Italian literature at Dartmouth College when I learned about a three-month program at the Moscow Art Theatre Studio School. I came to Moscow and happened to see Richard III at the Satirikon, which made a lasting impression on me. In fact, the play actually determined my future; it had a very powerful impact. In the play, everyone – the director, actors, production designers – all spoke the same language. The following year, Satirikon’s artistic director, Konstantin Raikin, was enrolling students for a drama course, so I signed up.

Today, I am involved in several projects in Russia and Great Britain. In Moscow, it is Lafkadio at the Masterskaya Theatre and Club, and Illusions at the Praktika Theatre.

About Theatrical Life Abroad

I liked London a lot – its parks, its air and its open people. It is not Utopia though: Their pragmatism can also get under your skin pretty quickly. Yet everything is thought through in order to make life comfortable. I don’t blame Russia; it’s just nice to be in London after Moscow. It’s nice to see people who are not so tired of one another.

About Lafkadio

Two American actors speak Russian in a very attractive way. A huge sheet of white paper is transformed into stage props right in front of the audience.It is a sad and funny story about a lion who learns how to shoot and what becomes of it. The story was created by the writer Shel Silverstein. Cazimir’s co-star is Odin Biron. Lafkadio will be performed on June 15 at the Masterskaya Theatre and Club.

Yet theatre life there is actually dull. Only a small proportion of Londoners are theatre-going. In Russia, they are trying to make plays as affordable as possible: You can actually go to see plays if you are a student, if you know someone in the theatre, etc. There are always full houses.

In England, however, you cannot get inside unless you pay, even if you are someone’s mother, friend, or lover. Paying for tickets certainly makes more sense, but the most important thing here is attention – the feeling that the event is a success. And the effect is weak when only 50 out of 100 seats are taken.

That does not happen at the plays I am involved in [in] Moscow, and it has nothing to do with me: We should give credit to the city and the administration of the theatre. It also has to do with the education of the Russian people. They come to see Fitzgerald’s plays because they read and like them. If you invite an American to see a Woody Allen play in New York, the effect will not be the same. In America, Russian plays are rarely performed. Literary culture in Russia is very strong: It is hard to imagine playwrights discussed on TV shows in the United States or Great Britain like it’s done here.

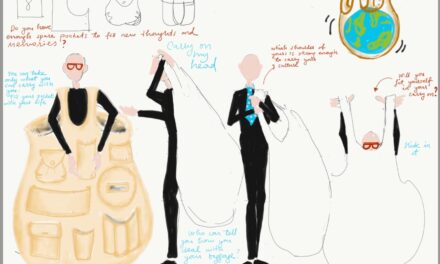

Odin Biron (L) and Cazimir Liske in Lafkadio performance. Source: Press Photo

For me personally, America offers more opportunities in that they lack theatres that could be considered a tuning fork of speculation – a place where people could go to ask themselves difficult questions about life. In America, theatre is no more than entertainment, generally speaking, although we do have some brilliant productions. In Russia, conversely, theatre is a discussion topic even among young people; it is taken seriously, the way sports in America.

In the U.S., if you originally say you will make a production in one and a half months, you cannot ask for more time later. In Russia, they do it all the time. Americans cannot even understand this: What are you doing there rehearsing; what have you been doing for two months?

About The Russian Language

You cannot really a separate language from culture. You need a different vehicle of thought to understand what is going on here. When I was helping teach Harvard students in Moscow, I realized that the Stanislavsky method could not be translated into a different language, just like they say Communism does not work in other languages.

It could take root only here because the language provides the necessary background. For instance, they have different associations with the Russian word that translates as ‘society’ in English. When I speak Russian, even my movements change, my voice becomes deeper, I am a different person overall. In Italy, I speak in a loud voice and tend to be late all the time.

I used to be very self-conscious about my accent; I wanted everyone to think I was Russian. I understand now that was wrong: I am not Russian, so why should I try to deceive people?

About Russia

Lafkadio is an easily movable production; it can be shown in any environment. We have performed it in orphanages and other most unusual places. We took it to Irkutsk, Novosibirsk, Nizhny Novgorod, and Salekhard. It is not really a lightweight play: Some people think it is for children, but we are very cautious about saying that. At a certain point, children do get involved in the performance: They perceive direct communication as interaction, and attention is distracted.

In Moscow, the audience is used to theatrical performances; but, for the provincial audience, each performance is an extraordinary event. They would not let us into Salekhard at first: They needed an authorizing document because the city is closed for foreigners. Then airport officials recognized us, made a call to some colonel and let us in. It’s a totally different scale event there. The audience there is much more appreciative; they are always waiting for us and asking for autograph sessions. They are even different in how they listen.”

I liked it best on Lake Baikal. I took a train there one summer with my fellow students – a four and a half day trip. With almost no money, just a bit for beer. You keep drinking to feel a little cooler. The place has a different energy, different people. We have some close friends there. In fact, I miss nature when I am in Moscow. I always go to the mountains when I get back home.

About Moscow

I like my work and the people I work with here. In the theatre world, there is no one who does not love the theatre and works just for the money. Money is a delusion. You are defined by what you do, so you must put your soul into everything. Unfortunately, many people are miserable, because they value other things. I am very lucky to work where I want.

About Bureaucracy

Work permits and visas are one of the reasons I am reluctant to work in Moscow. You have to obtain a work visa and can only work in one place. So, if I work for the Moscow Art Theatre [teaching acting technique], I cannot work for the Praktika Theatre. Likewise, if I have a work permit for Praktika, I cannot be involved in another theatre. Yet no one actually complies with this: It would be crazy. A teacher’s salary is absurdly small. I am always struggling with the documents. I do wish our governments would take it easy!

About His Favorite Places

I like parks: Gorky Park, Izmaylovsky Park, Hermitage Park and the boulevards. I now live on Trubnaya Square. It’s a nice place: Wherever you go from there, you have to take a boulevard. I can’t stand the underground anymore, so I ride a bicycle to get around. Yet it is a real challenge to stay alive on your way to work; people turn into monsters when they drive. This issue is long overdue in Moscow. I also like places from which you can see the city: some high spots, Sparrow Hills, tall buildings. Moscow lacks horizons to let people feel there is an escape.

First published in Russian in Moskovskie Novosti.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Ekaterina Vlasova and Moskovskie Novosti.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.