Anyone familiar with Chinese opera would recognise the role Kelvin Ng Kwok-wa is playing next. Posters for his new show depict him head to toe in black. On his head, a distinctive puffed velvet hat, paired with a matching Chinese jacket and billowing wide-led pants. His face is burning red, with arched black eyebrows. His glare is intense, and he holds a sharpened blade against his shoulder. This is Wu Song, a fearless warrior, but also a drunk, most likely on his way to slay a tiger.

Wu Song is a character from one of China’s four classic novels, Water Margin, published in 1589, a piece of work known for its vivid characters, racy language, and its alluring, enduring lead character. (The other classics are Romance of the Three Kingdoms, Journey to the West, and Dream of the Red Chamber). Wu Song is a martial arts character, flawed but full of spit and vigour, a moral defender who is also a bloodthirsty fighter, whose luck twists and turns faster than a race car on a circuit. Wu Song has been portrayed in Chinese operas for centuries, although this next outing will be markedly different.

The Wu Song in I, Wu Song, presented by a new young opera company, The Gong Strikes One, looks and plays the part. Many of the book’s famous scenes are included in the running order, including one in which he drinks 18 bowls of wine at a tavern, where an innkeeper warns him against crossing a nearby ridge inhabited by a dangerous tiger. Headstrong Wu Song ventures forth, meets the tiger and kills him barehanded. Yet in this show, there are no accompanying cast members. No tiger, only Wu Song. Unlike others, this Wu Song doesn’t sing his part; he doesn’t even talk. Instead, his action and the show’s music tells the story. And instead of being many hours long, like traditional operas, this retelling lasts just 90 minutes.

There has been a recent push to revive Cantonese opera since its heydey in the 1950s and 60s. One of the major opera styles, along with Peking and Kunqu, Cantonese opera dates back to the 16th century Ming dynasty, and draws from many regional Chinese opera styles, with additional influences from the Pearl River Delta. Operas are sung in Cantonese, the language of Guangzhou, where the style originated.

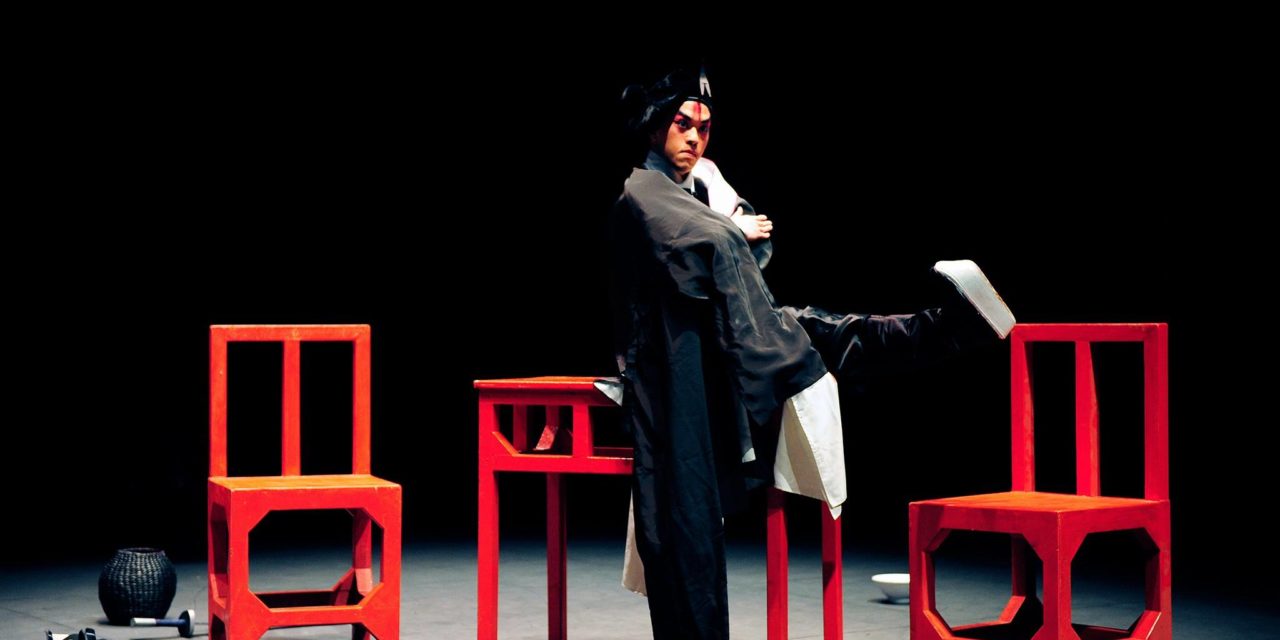

Kelvin Ng Kwok-wa’s metamorphosis – Photograph by Nicolas Petit

Although the United Nations designated Cantonese opera an intangible cultural heritage in 2009, interest had dwindled for many years. In 1999, the Hong Kong Academy for Performing Arts began a course in Chinese theatre to find new performers, and the Cantonese Opera Advisory Committee launched a scheme in 2009 to fund upcoming artists. Soon after, the Chinese Artists Association offered a Young Talent Showcase, where old masters of Cantonese opera passed on their talent and experience to train a new generation of actors. Now, finally, interest is once again blossoming. In 2018, the West Kowloon Cultural District is scheduled to open its new Xiqu theatre, an opera venue with 1,100 seats, and it has been running its Rising Stars of Cantonese Opera programme for emerging actors since 2014.

Lee King-chi, a founding member of The Gong Strikes One and the producer of I, Wu Song, says she began taking opera classes 20 years ago as a child when it was unusual for children to be learning Cantonese opera. These days, more people are thinking about opera, but that hasn’t meant much innovation in the art form. “Every day there is a show going on somewhere,” she says. “So, if you want to perform, you could, every day. You could be a very busy actor. But if you want to do a special play or create a new script, it’s hard.”

The Gong Strikes One is cutting a new stride, putting its emphasis not on the performer as much as his movement and the music he moves to. Most incentive schemes target performers, not musicians. This company thinks differently. “We think music can take centre stage,” says Lee. “We want to preserve the flavour of the drama by showcasing vocal and instrumental passages.”

Usually, at an opera, musicians are housed in a pit or in the wings of the stage — in sight of the performers but not the audience — and they form two sections. Percussion and the melodic ensemble accompany vocal roles and are often employed to respond to a character’s utterances, a practice called paak3 woh3 (拍和) in Cantonese. Instruments traditionally included the shuangpigu, a drum with a leather skin pulled tight over both sides of a wooden frame on both sides, which is used by the leader of the orchestra to cue his fellow musicians.

Alongside the drums is a combination of small and large solo gongs and cloud gongs, which are a set of 10 small gongs housed in a frame. Handheld wooden clappers, which are like streamlined castanets, and a small set of cymbals, are also in the percussion section. Fiddles, including the erhu and the sanxian, a three-stringed banjo, are among instruments in a strings section. During the 1930s and 40s, the use of Western instruments became popular, and musicians began incorporating violin, cello, and saxophone.

In I, Wu Song, the musicians will be visible, and they play only traditional instruments. Five musicians will play around 10 different gongs and cymbals using layered patterns, in rhythms that set the pace and describe the action, sometimes at a loud and frenzied rate. Chan Chi-kong, an opera devotee who grew up around performers — both his father and aunts were opera professionals — will head up a two-man strings section, with the piercing erxian contrasting with the mellower sound of bamboo strings to form a textured melody.

The Gong Strikes One was formed in 2012. Lee and Chan met through the Hong Kong Academy of Performing Arts (APA), where they both studied opera music. They put together a group of local musicians using only Chinese instruments and playing musical passages from Chinese opera at a variety of concerts and events. The chance to create I, Wu Song is a “dream come true,” says Lee. She recalls a moment when Chan was asked by a professor at the APA what he wanted to do after school. “This is pretty much what he said,” she says.

Percussion in I, Wu Song is put centre stage, but it was the legendary character that inspired the piece. Lee had watched the character and appreciated his physicality from her place in the pit when she played in another staging of the opera. “He has such brilliant movements, such a distinctive appearance, this was a chance to showcase his looks and his moves,” she says. Despite doing away with the vocals, Lee and Chan have kept to much of the traditional story, using exaggerated operatic movement to propel the story with a script created by Chan and Kelvin Ng, the 24-year-old performer playing the lead.

In opera, make-up tells as much about a character as costume. As he applies the bright, raging red face paint that represents Wu Song’s violent, drunken character, and draws on two thick black eyebrows, Ng’s young, boyish face distorts. Later, with an assistant, he wraps a damp, five-metre-long black chiffon strip of cloth round and rounds his head that has the effect of raising his eyebrows and stretching his kohl-rimmed eyes outward. The look is strong and powerful. But it is when he projects a hard, staring glare into the camera that Wu Song really comes to life. Those piercing eyes are a credit to his performance skills, says Lee. “Your teacher can move your arms or your legs, but he cannot move your eyes for you,” she says.

Ng joined a children’s class for opera and then trained under a Peking opera master for many years, and specialises in martial roles. He flexes in his costume and fixes a long pony tale hairpiece to his headband before whirling his head in circles, a move that in opera signifies frustration or grief. All the time he continues to hold that glare. The heightened action is an exhausting challenge, says Ng. He really wanted to project Wu Song’s depth, despite not being able to sing the role. “I needed to know how to show the feelings inside,” he says.

In opera, lots of moves are symbolic, many related particularly to the type of role an actor takes on, whether it’s the clown, the gentleman or the warrior. But it isn’t hard to spot Wu Song’s rage, whether you know the practiced gestures he uses or not. And that is the beauty of I, Wu Song, says Lee: its abstraction makes it accessible.

I, Wu Song plays at the Hong Hong Cultural Centre from June 10 to 11, 2017. For tickets and more information, visit here.

This article was originally written by Elle Kwan for Zolima CityMag. Reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Zolima CityMag.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.