In 2013 Ignacio Bartolone created a buzz with his first play, Piedra sentada, Pata corrida (English title: Sitting Stone, Running Foot). He has gone on to establish himself as a key figure in the new writing scene in Argentina with La piel del poema (The Skin of the Poem, 2015) and La madre del desierto (The Mother of the Desert, 2017), but his first play continues to delight audiences in the city seven years on, playing in a weekly late-night slot on a Saturday evening at Teatro El Extranjero—in the city’s Abasto quarter.

An indigenous tribe on the point of extinction in a remote area of Patagonia, the (invented) Lechiguangas, serves as the starting point for a farce asking important questions about who is given voice in society. A group of tribespeople return home after a night of cannibalism; the two lads speak in an invented language with shavings of Spanish; the father figure encourages the boys; the mother is not approving of their cannibalistic practices; a dog warns of the arrival of an outsider representing supposed “civilization.” The tribespeople speak in a language derived from the conventions of gaucho literature, an artificial language rooted in literary tropes and conventions, and their struggle is one to stop the white man moving in to annihilate their way of life in the name of “progress.” Cannibalism here serves as a metaphor—the endangered people seeking to eat before they are eaten. When the young supposedly idealistic Spaniard, Luciano Ceballos arrives, with promises of “civilization,” the community may initially be seduced by the wares he offers but they soon have their own response to what he represents.

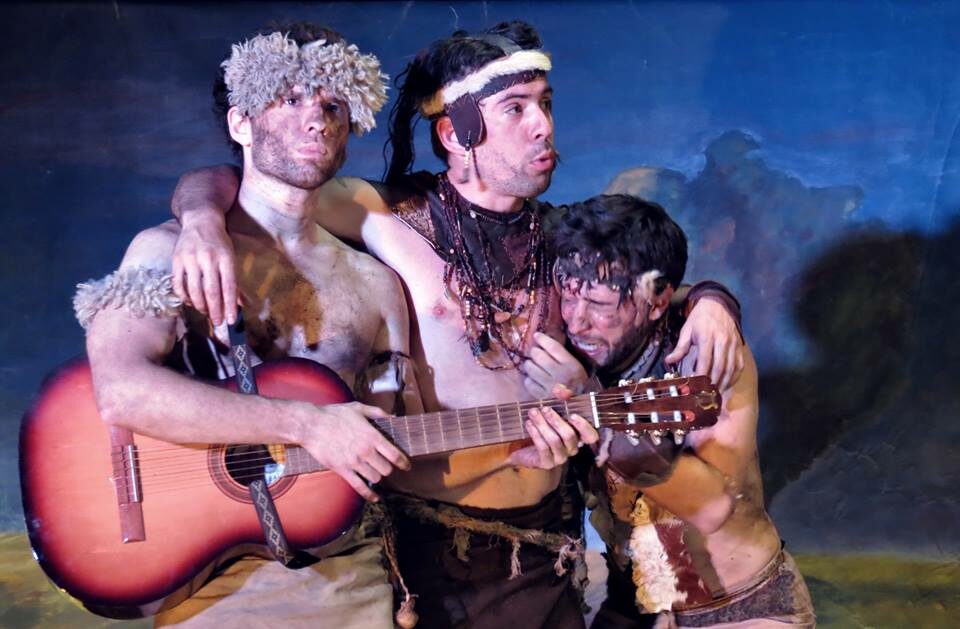

The piece’s inventiveness lies in a theatrical language that merges the colloquial and literary in a poetic register that is both playful and audacious. Gender politics come into play as the mother, played by Cristina Lamothe, has her own ideas on the proposals put forward by the adrenaline-fuelled men and comes to take control of the tribe as its first woman cacique (chief); this is a mother that won’t be intimidated. Bartolone’s production merges slapstick with a choreography that plays out the dynamics of the tribal family rooted in an understanding of what patriarchy means and how it is to be performed. The influence of Ricardo Zelarayán is palpable but echoes of Borges’s narrative games are also in evidence. There’s an evident parody of the founding fathers of Argentine literature, canonic writers like Cesar Aira, Lucio V. Mansilla and Domingo F. Sarmiento. The burlesque elements emerge in musical numbers—a guitar serves as a gloriously anachronistic accompaniment—and in pacing of the action that is always frenetic, animated and exaggerated. Bartolone crafts a piece about how indigenous identities have been packaged and subsequently repackaged for consumption by white writers and the choice of white actors to play the roles is part of a political decision on Bartolone’s part to highlight this performed identity as discomforting and ongoing.

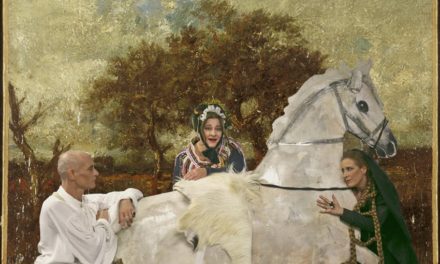

The dog Faustino, bouncing around the stage in Ariel Pérez de María’s energetic performance, takes on a prophetic presence. At the play’s opening, he has lost his bark but speaks to the audience, reciting a gaucho poem that positions the piece within a particular heightened literary language. The in-yer-face performance style, eschewing the anthropological, further dissects the “constructedness” of the image of the other within the Argentine culture. Paola Sigal and Mariana Gabor’s painted backcloth too presents a landscape constructed through a colonizing imagination. The backdrop is ever so slightly off-balance, further suggesting a world off-kilter. There is something (intentionally) childish also in Paola Delgado’s costume design. This is a stage picture constructed through the broadest of brushstrokes, almost like a comic book. Bartolone’s more recent works may be more sophisticated in their structure and gameplay, more tight in their dramatic construction, but the young and highly vocal audience who attended the 11 pm performance showed the pull that his unsettling vision of Argentina’s colonialist atrocities—the focus of powerful (and also genre-bending) recent films like Lisandro Alonso’s Jauja (2014) and Lucrecia Martel’s Zama (2017)—has on contemporary audiences.

Piedra sentada, Pata corrida plays at Teatro El Extranjero Buenos Aires on Saturdays at 11pm.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Maria Delgado.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.