What is it like to get on a bus that does not follow a regular route through the city but remains still and turns into a theatre stage?

It was one of those times when stage space becomes as significant as a staged performance. Following the formalism of modernist and avant-garde theatre in the wake of the 1950s and 1960s experiments that moved performances out of traditional theatre buildings into real, social spaces (in the form of happenings, documentary theatre, living theatre, café théâtre, fringe theatre etc.), an increasing number of contemporary Greek directors choose to set theatre outside theatres. The use of gardens, museums, streets, old factories, means of transport and archeological sites for spatial experiments has become no less than a trend in current theatrical life in Greece.

The National Theatre of Greece in partnership with The Athens Urban Transport Organization set Chekhov’s The Bear inside a city bus. Under the direction of Sofia Marathaki, actors Ieronymos Kaletsanos, Elissavet Konstantinidou, and Fotini Papachristopoulou drive through the city of Athens carrying around a miniature of the Chekhovian world. The bus-performance is meant to travel around neighborhoods—an allusion to the booth stages of medieval and renaissance theatre and some of their later, adapted forms, like the Greek traveling theatre groups of the 19th and early 20th centuries (the so-called “bouloukia.”)

Combining traditional mobile theatre structures and modern experimental ones, the bus is at the same time a means to move (the performance) and a place to stand (and perform), the container which shapes and is shaped by the contained, the messenger and the message. But is it so? The actual space inside the bus is split into two parts. The front side of the vehicle demarcating the stage, the actors’ energetic space, and the back, furnished with seats, serving as the auditorium. Five seats at the back are reserved for the lighting and sound control operator and his equipment.

The Bear is set in the drawing room of Elena Ivanovna Popova (Fotini Papachristopoulou), a rich widow who insists on keeping herself and her housekeeper Sonja (in Marathaki’s version the Popova’s footman Luka is substituted by a maid, played by Elissavet Konstantinidou) locked up after seven months since her husband’s death, as proof of her eternal faith and affection. Her mournful weeping is suddenly interrupted by Grigory Stepanovich Smirnov (Ieronymos Kaletsanos), a lieutenant who demands to be paid the money her late husband still owes him. The widow’s stubborn denial to pay the debt leads to arguments, insults, pistol duels, and eventually to love confessions.

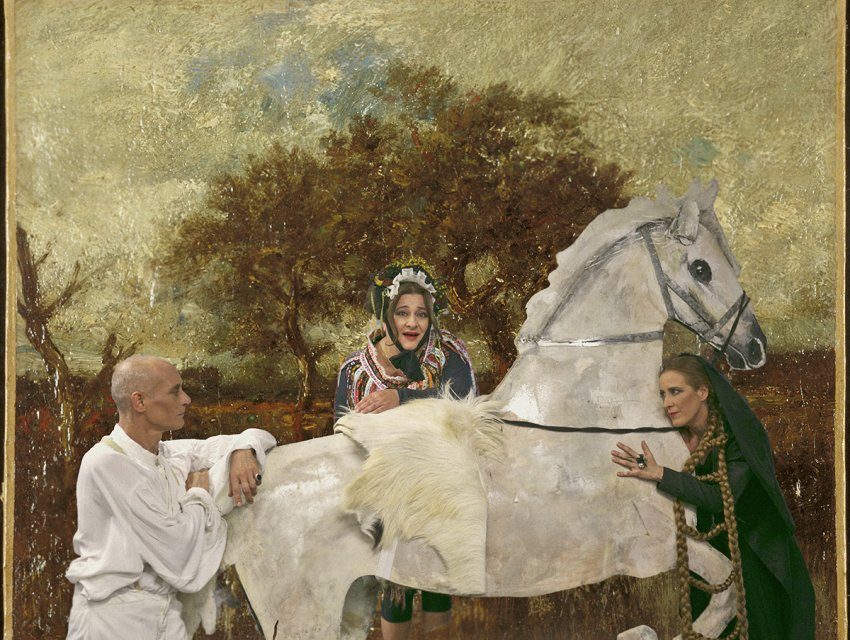

Anton Chekhov’s 1888 one-act comedy is often read as a battle between the sexes and that aspect of the play remains central here—even though the financial difficulties of the leading character bring in an additional conflict for the Greek (economic crisis-stricken) audience. Marathaki makes use of the space both inside and outside the bus; spectators look through the bus windows as lieutenant Smirnov arrives on his pantomime riding horse (an allusion to Commedia dell’ arte). The tiny space of the interior reinforces the claustrophobic environment of Popova’s house (after the entrance of Smirnov the windows remain closed) and builds a relationship between actors and spectators that creates a cinematographic experience. This, however, seems to raise a problem. In smaller spaces, the level of acting energy has to be lower—and so it was. But even though low energy doesn’t necessarily imply the extinction of a performance’s subtlety, tiny spaces inevitably lead to a weakening of tonality and acting qualities. Smirnov portrayed as a gentleman who expresses his anger sparingly and dispassionately (where is the Bear?), while his and Popova’s arguments lacked climax and comic mood swings. The director ingeniously tried to compensate with music and light design (to highlight the lieutenant’s temper changes), visual jokes (Sonja’s hyperactivity) and pop culture connotations (Popova as Lara Croft) but excessive repetition rendered them less effective.

Ieronymos Kaletsanos captured well both the dramatic and the comic aspects of Smirnov and successfully embodied the latter’s blending of childish bellicosity and genuine romanticism. Fotini Papachristopoulou as Popova takes a while to settle into the performance’s rhythm; at the very beginning, her mournful sobbing comes as a result of external comic acting and not of a deep connection with the material. But as the performance proceeds, she gradually builds a character whose comedy arises from the role’s tragic dimension; ultimately, “the tragedy and the comedy are formal concepts that embrace one and the same thing” [1]. Elissavet Konstantinidou’s Sonja reveals both the brashness and cowardice of a Moliere maidservant.

The fussy but effective set and costume design of Eleni Manolopoulou creates a surreal environment that evokes the contradictions between the characters’ being and appearance. Employing a similar contradiction, the interior of the bus, covered with funeral notices of Popova’s dead husband, adds to the depressing, gloomy atmosphere of the room, but is at the same time undermined by the notices’ ironic content, by the grotesque bust of Popov, and women’s bizarre attire (Popova’s rope ladder hairstyle is reminiscent of Grimm’s Rapunzel).

All in all, the performance remains lively and perfectly enjoyable throughout, but it might leave one perplexed as to how the choice of a bus as a theatre stage could, after all, be dramatically significant. Although the idea of a wandering stage project promotes an easy-to-access-theatre that is strengthened by free admission, one may wonder how this can be achieved by an average of four performances in each neighborhood and the space efficiency of fourteen spectators.To speak with Marcuse, “aesthetic form is not opposed to content, not even dialectically. In the work of art, form becomes content and vice versa”[2].

Physical and energized space must establish an organic relationship; the form has to constitute an essential aspect of the artwork as a totality in order to be effective.

The Bear | Anton Chekhov

Theatre Express

National Theatre of Greece–Athens Urban Transport Organization

Notes:

[1] Friedrich Duerrenmatt, Problems Of The Theatre, Friedrich Duerrenmatt and Gerhard Nellhaus. The Tulane Drama Review, Vol. 3, No. 1 (Oct. 1958), p. 20, https://www.jstor.org/stable/1124972

[2]Hebert Marcuse, The Aesthetic Dimension: Toward A Critique Of Marxist Aesthetics, Beacon Press Boston, 1978, p. 41.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Maria Sikitano.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.