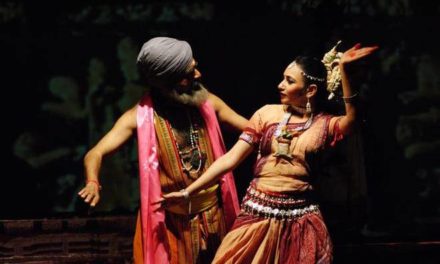

Staged at the ongoing 8th Theatre Olympics, Sabir Khan’s Doodhan mirrors the hardships of Kalbeliyas, the traditional protectors of snakes.

We tend to believe that we are moving forward but sometimes a little anecdote or observation jolts you out of complacency. You realize that the march of modernity is not a straight line and that many traditions and customs that we left behind were not as atavistic as we were made to believe. This is precisely what happened with veteran director Sabir Khan whose Rajasthani play Doodhan was staged recently at the ongoing 8th Theatre Olympics.

The story follows the life of Kalbeliya community, worshippers of Lord Shiva and snake charmers. In the past, they caught snakes to release them in fields on Nag Panchmani to save crops from rats and received food grains in exchange. With Wildlife Protection Act in 1972 coming into force, they were rendered jobless, forcing them to kill snakes—traditionally prohibited—and sell the skins which are in high demand. Doodhan, the Sarpanch’s daughter protests against this practice and ultimately sacrifices her life. Khan’s play brings to light that there is more to the community than their folk dance. Khan heard about Kalbeliyas from well-known author Dr. Tara Prakash Joshi and asked him to write a play. “I was hooked on to the true story of Kalbeliyas and requested Joshiji to pen a play on them.”

Excerpts:

On what inspired him to make Doodhan

Dr. Tara Prakash Joshi, explained me the scientific rationale and philosophy of Kalbeliya nomad community in taking care of snakes which I found a novel and interesting subject. As Lord Shiva’s followers, they never killed snakes and eked out a living by helping farmers. So they were into conserving ecology by protecting crops. With Wildlife Protection Act coming into being, Kalbeliyas source of income disappeared while increasing consumerism led to a demand for snake skins. This forced them to start killing snakes. Caught in the upheaval of change, Kalbeliyas gave up their age-old customs, and instead of protectors became killers. That pathos in the change of life’s philosophy touched me and I requested Joshiji to weave a play around it. He met the community members and Sarpanch several times to gather more information and wrote the play.

Also as worshippers of Lord Shiva, they represent the philosophy of co-existence because in His abode one finds snake, peacock, bull, and rat. All of whom are either prey or predator but they live peacefully.

On how deeply is ecological protection ingrained in Indian ethos

It is deeply embedded. For example, Bishnois, do not kill animals and fell trees. Likewise, Hindus worship peepul tree and among many Muslims cutting of neem is forbidden. This ensures shady trees, check on carbon dioxide and availability of many medicines. Kalbeliyas are unique because the entire community did not kill snakes and risked their life dealing with these venomous reptiles. Interestingly, the word “kal” means death and “belia” to play, so Kalbelia means those who play with death.

On why the play ended with Doodhan’s sacrifice

Initially, the play had a happy ending but I wanted an anti-climax to emphasize the sufferance of Kalbeliyas. Inspired by Sati tradition of self-immolation, I incorporated Doodhan’s sacrifice in her father’s agni kund at the end. This was the highest form of protest she could register, hoping that her father and the community will be influenced to stop killing snakes. Incidentally, Doodhan’s father name is Daksh Nath as Sati’s father was Daksh.

On highlighting several aspects of Kalbeliya’s life

Besides their core philosophy, I found several fascinating aspects about them. These were observed by Joshiji and in our discussion, we decided to include them in the story. For example, they have a democratic process to elect their sarpanch. The person has to be either unanimously selected and when that is not possible, there is an election. There is no tradition that a sarpanch’s son automatically gets the post or that only rich and powerful could contest. The election is free and fair.

The rights of Kalbeliya women are well protected. In the play, Charpati Nath decides to leave his wife to bring another woman home. He is told by the Sarpanch that he is free to do so but his temporary house, belongings, including snakes, will be handed to the wife. Contrary to normal tradition, among them, a man has to leave the house and not the woman.

On choosing theatre as a profession

In Jaipur, elite Muslim marriage ceremonies included a programme called “Nakaal” or “Jalsa.” In that tawaifs danced till midnight after which a play was staged. This was done by nakaals or bhands. The play would go on till 4 a.m. and it would be about Laila Majnu, Shirin Farhad, Sultana Daku, etc. Watching them as a youngster, I became fascinated by stagecraft. From there my love affair with stage started and still continues (laughs). Initially, I read many plays and how they are directed. Later in 1975, I attended a workshop conducted by Rajasthan Sangeet Natak Akademi and started working with well-known theatre personalities.

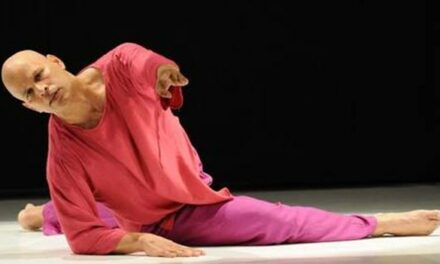

So far I have done 40 plays with repeat shows of each in the last 40 years. Over time I have evolved as a director. Earlier I believed that a realistic play had to follow a certain format but later realized that presentation depends on content and context. So I started taking elements from folk, classic, modern, street theatre styles, among others. Also, I started using music and dance as an integral part of the theatre. Only one thing has not changed—my commitment to stage a play not just for entertainment but also to highlight an issue.

On working with doyens like Habib Tanvir, Bhanu Bharti, and S. Vasudeo

Working with these veterans was a learning curve as evident in my work. With Bhanu Bharti I did the play Pashu Gayatri, taking care of the lights and other technical details. Based on tribals, it drew me to folk and Lok Natak genres. Also, I grasped from him how to adapt the folk stories in modern context and give them a touch of realism.

Habib Tanvir Saheb was an institution in himself and I assisted him in Charandas Chor. Thereafter, I attended his workshop too. He taught me about music, acting, etc. Habib Saheb insisted that theatre music must be composed specifically for it, its content and presentation and not borrowed from film songs. In this play, the music is by Mahadev Nath Sapera, a Kalbeliya and the choreography is based on their tradition.

Having worked and acted in several of S. Vasudeo’s plays, I learned the basics of theatre from how to move on stage, manage space, emote, and express through gestures and movement. Having been an actor helps me a great deal in explaining scenes to my actors and realize their problems and shortcomings.

This article originally appeared in The Hindu on February 23, 2018, and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by S. Ravi.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.