Director Ravi Taneja’s Konark, underlined that art cannot exist in isolation.

A multi-faceted creative personality, Jagdish Chandra Mathur (1917-1978) is today fondly remembered by theatre lovers in the Hindi region for plays remarkable for their incisive social comments. Among his regularly staged dramas are Konark, Shardiya, Pehala Raja, and Dashrathnandan. Konark is considered his theatrical masterpiece both in terms of content and form. As a part of Mathur’s birth centenary celebration, Konark was presented by Collegiate Drama Society at Shri Ram Centre recently under the auspices of All-India Radio. The presentation of the play was an occasion to pay tribute to the playwright who was also the Director General of All-India Radio (1955-1962) and is credited with introducing a number of innovative programs and revamping with a view to give an Indian perspective to programs of AIR. Apart from introducing broadcast of plays, which has a distinct format to adapt to the medium of radio, the broadcast of Vivid Bharati, a popular program was added to the repertoire of the AIR. An ICS Officer, he was one of the founder members of Sangeet Natak Akademi and chairman of National School of Drama Society. It is heartening to know that Sangeet Natak Akademi is organizing a seminar on Mathur as well as a festival of his plays. Sahitya Akademi has already organized two seminars recently.

Directed by Ravi Taneja, a seasoned director and actor of Delhi stage, who did Konark more than a decade ago for a college, revisiting this revived production of Konark has its own rewards. The presence of some of the top brass of AIR and family members of the playwright on this occasion gave the event an aura of cultural dignity and sweet nostalgic feelings.

Innovative character

Revisiting the structure of Konark, one is struck by its innovative character. The point of central focus is the revolt of craftsmen against an oppressive regime which treats them as outcasts, discriminates against and ruthlessly exploits them. There is an undercurrent which suggests that creativity to be meaningful should not be done in isolation from society and after all what artist creates is a reflection of the productive forces of his age. What is most admirable is that there are a few thematic strands running the play like the guilt of betrayal of a lover who abandoned his beloved and their little son and the royal intrigues involving army chief who revolts against the king to usurp his kingdom. These strands are weaved seamlessly into the central theme of the play. There is another noteworthy aspect of the script, revealed in an almost imperceptible way, the relationship between Vishu, the chief craftsman, and Dharampad, the young genius craftsman. The way long-separated father and son unite evokes a feeling of poignancy, eschewing melodrama.

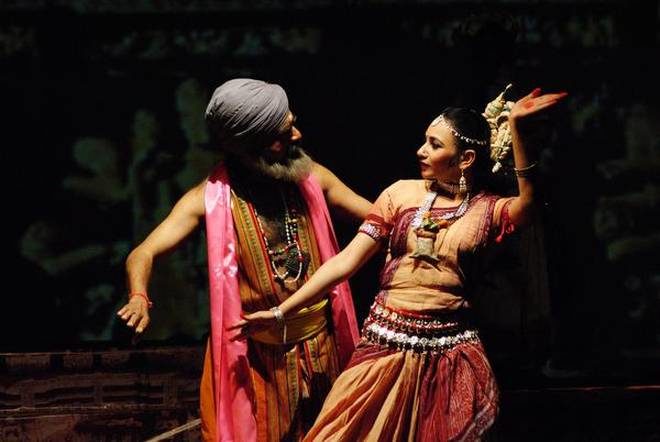

A scene from Konark. Photo credit: Special Arrangement

The entire action unfolds on the site of construction of the temple. The suggestively designed set, the imaginative use of offstage music captures the ambiance of Konark temple, an architectural marvel being created by craftsmen using their hammer and chisel, giving shape to stones, who are inspired by King Narasimhadeva who ruled in the 13th Century in Odisha. However, at the most vital moment when it is time to rejoice, the construction is struck with a critical technical snag. Chief craftsman Vishu miserably failed to solve it.

Enter a young man, Dharampad, who is able to correct the technical glitch—lo and behold craftsmen’s years of dedication and passionate involvement in the creation of a wonderful temple bear fruit. But a tragic turn takes place. The sense of collective joie de vivre turned into bloodbath and destruction.

As the King is inside the temple in the midst of craftsmen and workers, rumblings of war cries are heard which gradually become deafening. All the craftsmen along with the king are surrounded by rebel forces. When everybody is shocked, finding themselves without forces to retaliate, Dharampad takes leadership into his own hands, exhorting his artisans and technicians to unite, destroy the very temple they have built and use heavy stones to use as a missile to inflict defeat on the traitors and enemies of artists.

The play opens with a song that gives us the sense of a distant past to which the drama is set. A group of Kathak dancers creates slowly, beautiful and rhythmic poses with craftsmen standing by them with their hammer and chisel. The choreography by Beena Bhadhwar imparts visual beauty to the production with dancers creating a variety of poses to create the illusion of stones gradually acquiring multiple poses that are objects of beauty.

Madan Dogra as Vishu, the chief craftsman, and Atul Jassi as the benign and art patron King Narasimhadeva, give convincing performances. Their portrayals bear the stamp of their mature artistry. Ajay Katariya as Chalukya, a traitor who attempts to dethrone his king, acts admirably. Naveen Gupta as Dharampad, the young rebel, a genius and an organizer imparts vitality and conviction to his portrayal, winning the applause of the audience.

This article originally appeared in The Hindu on June 1, 2018, and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Diwan Singh Bajeli.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.