Thrissur Kathakali Club has launched a Kathakali Workshop Project to familiarize viewers with the language and syntax of the art form

Until the 1980s, those who sat through night-long Kathakali recitals were usually familiar with the epics, although they might have had trouble in following the meaning of each and every gesture or literary-text sung by vocalists. During their childhood, they must have had their grandparents to tell them stories from the epics, most of which formed the repertoire of Kathakali.

However, within a quarter century, the audience for Kathakali and similar highly evolved art forms has declined.

The composition of a contemporary audience for these art traditions is usually restricted to the middle-aged and the elderly. Not more than a handful of youngsters turn up to watch Kathakali and Mohiniyattam recitals even in the public domain, let alone in temple courtyards. This poses a grave threat to the continued existence of these traditional arts.

Having realized the density of an impending crisis for Kathakali, Thrissur Kathakali Club has launched a Kathakali Workshop Project. The very objective of the project is to create ‘Kathakali literacy’, which would help people connect with this rather esoteric artistic legacy.

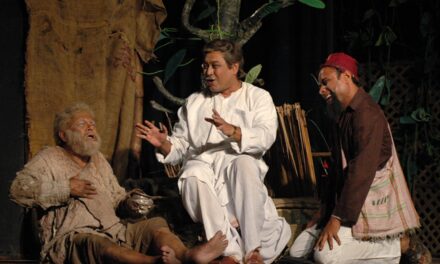

Kalamandalam Balasubramanyan, a seasoned Kathakali artist, initiated the first workshop within the Thekke Madhom in Thrissur.

During a Kathakali recital, most rasikas do not notice the differences in movements related to the entry and exit of many a character in Kathakali. The differences are based on the type of characters and the contexts concerned. Balasubramanyan demonstrated the behavior of select characters during their entry and exit.

For instance, a Pacha character denoting noble qualities, as a rule, enters without thiranokku or any specific steps behind the curtain, while the Kathi (with shades of villainy) characters have a customary dance behind the curtain and some yelling before the thiranokku.

Bhimasena, in the first part of the play Kalyansaugandhikam, does a “Sauryagunam” preceding which is the slokam “Sastrardham sakrasoonau.” The slokam here vividly describes Bhima’s uncontrollable anger towards the Kauravas, and therefore the actor in the role enacts the essential meaning of the words. Balasubramanyan did this with elan. Slokams, in general, are seldom enacted.

The majestic entry of Lalitha in the play Narakasuravadhom is a class by itself. The sringara padam of Bhimasena to Panchali in Kalyanasaugandhikam is in an unusually slow-tempo of 32 beats. The actor did the beginning portion of it impeccably. Similarly, Arjuna addressing his father, Lord Indra, in the heavens was portrayed exquisitely.

The slow-tempo scenes more often form the core of classicism in Kathakali. Hence, if one is able to grasp the movement vocabulary of characters in the plays of Kottayath Thampuran, he/she will become competent enough to develop a taste for the subtleties in Kathakali.

All in all, there will be 24 workshops spread over a period of one year. In the coming months, eminent actors, vocalists, percussionist, and make-up artists are expected to analyze every component of Kathakali in such a way as to benefit those who are eager to learn the ins and outs of this acclaimed dance-theatre tradition.

The uphill task of the organizers is to ensure a wider outreach for Kathakali amongst the youngsters.

This article originally appeared in The Hindu on February 28, 2019, and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by V. Kaladharan.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.