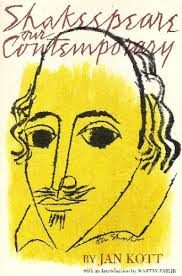

“Shamanistic charlatanism!” “A pernicious influence on Peter Brook!” Like a Greek chorus the accusations flung at Polish critic Jan Kott when his ground-breaking book Shakespeare Our Contemporary exploded onto the international theatre scene in 1964 was almost apocalyptic in their virulence.

Which begs the question – why the need for an all-day conference on Jan Kott, this “charlatan” Shakespearean scholar (and a foreign one at that) in 2015? What do we have to learn from this critic who died in 2001, and whose best-known work was half a century ago?

Of course, Jan Kott’s Shakespeare Our Contemporary took a little time to cast its “subversive” tentacles across the globe, but when it did, it was to open arms. As one American critic commented: “In America, he was hugely popular, Kott was competing with The Beatles–his book was a manifesto at a time of manifestos.” But what exactly is his legacy? What are the myths about “Polishness” and Kott’s political Shakespeare? How is Kott being interpreted today? In the cozy rooms of The Rose Theatre on a rainy day in Kingston, we are about to find out.

It seems Jan Kott was a busy man – aside from his theatre involvement, he was a political activist, critic, and theoretician. But even more remarkable was his life. Born in Warsaw to a Jewish family (later baptized Catholic), he lived through the war in Poland, seeing death and danger on a daily basis. Spending three years in the resistance, he also joined the communist party at a time when discovery meant an automatic death sentence. Posing as a doctor for cover, he was forced to deliver a baby as proof, using details he half-remembered from a novel. Nor did the threat come solely from the Nazis – he was once almost hanged by the Soviets as a German because of a German railwayman’s coat he’d filched to keep warm. In short, Kott knew what it was like to feel repression and persecution first-hand; to see the whole moral order evaporate in the blink of an eye. This sense of precariousness he tapped into brilliantly when reading and interpreting Shakespeare, and his mission through his seminal book was to make Shakespeare relevant to everyone – people from all classes from reader to scholar, and to show that the Bard was not writing about a dusty bygone age but about the here and now, about our own history as well as previous generations’, that along with being an Elizabethan playwright he was also – ineffably – our contemporary.

Kott’s significance covers a lot of ground: his meta-theatricality, his philosophy, his art – all have left an indelible imprint on theatre and its practitioners. Indeed at this conference for every paper presented there were contradictory stories, rumors, and plain old gossip to counter the myriad hypotheses presented here. This rarified and one-off occasion was, in a word, riveting. There were very young scholars flexing intellectual muscle (still at virginal phases in their research), others who had brushed shoulders with the great man and afforded him a guru-like status. There were veterans of post-war theatre; his contemporaries who shared many stories about the cultural climate at the time, describing him as a gem in a symphony of beige, and there were also others who doubted Kott’s legacy and, most controversially, his sincerity.

Indeed, some academics at this conference confessed to there being in addition to the praise, a resistance to Kott during his reign; some questioned whether subsequent generations had absorbed Kott through osmosis rather than propaganda. Personally, after listening to so many speakers it was difficult to tear this man’s legacy away from the emerging counterculture of the time. For all intents and purposes, Kott blew “romantic” theatre right out of the water, in the same way, that punk, say, had spat on progressive rock. It was a point of no return.

Much to the consternation of traditionalists, Peter Brook, and Peter Hall held Kott in critical esteem and he subsequently became a messianic influence upon them; to add insult to injury he also preferred using actors as reference points instead of quoting other critics – Kott was a man of the theatre, immersed in theatre practice and never simply seeing Shakespeare as words on a page (his descriptions of how a modern director might approach Hamlet, and of certain key moments from post-war Polish productions of Richard III, are among the most thrilling and vivid things in his book). A panel at the conference discussing such issues (John Elsom, Ben Nightingale, Ned Chaillet and Ian Herbet) underlined the point: “Kott’s book inspired the study of Theatre to emerge, it used Shakespeare, Our Contemporary in the construction of Theatre Studies modules.”

Another academic, Graham Holderness, described how his first experience of Shakespeare had been via a tiny black and white TV, in a council flat, in Leeds. Holderness went on to read Jan Kott at college and was blown away by how much it had revolutionized Shakespearean productions: “Shakespeare is rooted at the time it was written but within a universal nature.” As the day passed, arguments flew back and forth: what did “contemporary” mean? Wasn’t theatre always “contemporary?” How much had changed in political life since Shakespeare’s day? There were panels covering the ‘human essence’ in Shakespearean drama, Kott’s place in Romanian theatre, his relationship with the Theatre of the Absurd and Greek Drama. Indeed, it would seem Jan Kott is a Pandora’s Box of philosophical meanderings. It was always going to be difficult to cap the whole experience at the Rose theatre, but a performance Kage Where K For Kott, an avant-garde theatre piece with Filippos Tsitsopoulos, was a novel end to a furiously inspiring debate.

Jan Kott (1914-2001)

As I left the auditorium and headed out beneath the angry black clouds haunting Kingston, I was reminded of a quote picked up somewhere during the day: “Theatre made Kott bear the intensity of life”. I sank into my scarf as I faced the tempestuous wet weather, broken umbrella in hand, repeating Kott’s own words to myself too: “This is true of life as it is of theatre.”

This article originally appeared in Central and Eastern European London Review on January 3rd, 2015 and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Valenka Navea.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.