Looking at the titles in the InlanDimensions theater lineup, I was hard put to find a common denominator. The archive works and the latest Japanese and Hong Kong shows featured at the festival were a medley of contemporary East Asian theater. They did share a commonality though. And while it’s hard to say whether it was intentional or not, one thing is certain: the themes of the limits of understanding and humanity tackled during the festival seem more than relevant now.

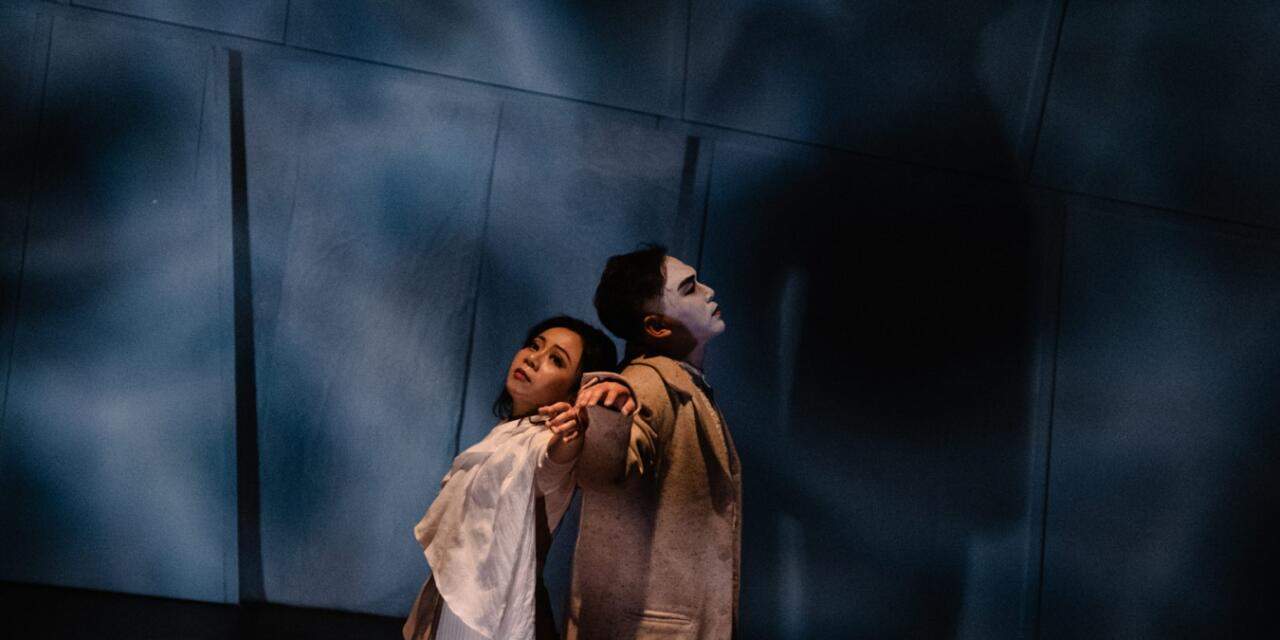

The stage slowly lights up. The actors gather around a mandala projected onto the floor as if to belie the words ‘in the beginning there was chaos’. Instrumental to order and harmony in A Dream Play (Alice Theater Laboratory, dir. Andrew Chan) are the beginning, dreams and death. Everything that befalls Agnes on earth is chaos. The daughter of Indra is at once non-human and quintessentially human, which will lead her to her doom. She is the only character that retains her own natural face ‒ the others, with their white-painted faces, are like phantoms. Their customs, laws and aspirations, though described in a language that Agnes speaks, are inaccessible to her. She is trapped in the absurdity of earth on an almost empty stage with a (locked) portal to the riddles of the universe, and she cannot escape. Her lofty words are interrupted by the four deans and the grotesque dance of the ballerina. Her vow of love is interrupted by the maid plastering her room with old newspapers until there is no air she can breathe. It soon turns out that the door that was to hide the riddle of the universe hides nothing. The kaleidoscopic scenic images are disturbingly similar to one another as they are peopled with characters with similarly whitened faces, wearing similar clothes and voicing similar complaints. People cannot understand Agnes. Are the differences between Agnes and them unbridgeable? Do they render any dialogue impossible? Perhaps it is the lofty sermons that jar with the reality? The final scene brings the actors around the mandala again ‒ death, or perhaps sleep, is the way out of chaos.

Can this exit be painless? Is it possible to restore communication and a common language? In the dance performance Still Human (4 Degrees Dance Laboratory & Huen Tin Yeung), attempts to communicate and break free from bondage prove painful. The dancers tied with rubber bands cast off their bonds with their movements. Almost every snap is accompanied by pain as the elastic bounces off the skin. We hear unpleasant snaps, hisses, clenching teeth. Once the dancers are almost free, another, equally confusing trap is introduced. Two dancers, a man and a woman, their backs tied together, try to gauge who has the edge: they pull in opposite directions and perform complex lifts, irritating their skin with the rubber bands. Just when it seems that some common ground is reached, their common direction collapses, as if it wasn’t important to free oneself at the price of collaboration, and as of the act of potentially mutilating oneself was the idea behind their actions. But if this is the case, and each dancer is left alone with their ties and pain, is there any point in achieving momentary communication? At the end of the show, the dancers reenact the initial choreographic sequence together. The tempos change slowly, and the dance loses its individual character. Again, the dancers put on the rubber bands and the choreography repeats itself ad infinitum ‒ the recording stops before it comes to an end. Moments of communication, of freedom and a feeling of physical discomfort that brings home humanity ‒ is this the way left to communicate/agree and be human? Yet it seems that this vicious circle is effective to a point ‒ it allows reclaiming physical presence here and now.

Questions about the limits of understanding between human and non-human are addressed in Grass Labyrinth (dir. Koike Hiroshi and Danny Yung), a piece which explores the real and the supernatural in its four parts, “Water,” “Moon,” “Mirror” and “Flower”. The choreography interspersed with poignant singing transports the audience seamlessly between the two realms. Some of the walls on either side of the stage are ordinary, others allow you to see what is on the other side. The actor wearing a Noh mask who stands behind one of them transports us to the supernatural sphere for a brief moment. He performs a slow dance with fans and only when we see him up close on camera we notice that he wears the Noh mask on the back of his head ‒ so tradition is illusory and subverted here. The doors and frames (painting frames? window frames?) are moved around by the dancers. This shifting labyrinth is supplemented by (extra)ordinary objects: a paper ship, chairs, a carpet, an umbrella, high-heeled shoes. The objects are sometimes used for their intended purpose: the umbrella is unfolded and the carpet rolled up and down. After a short while, however, the umbrella becomes a weapon that is used to kill one of the dancers while the carpet slowly vanishes from view behind the wall. It seems that the mis-en-scène, with its split into the real and the unreal, begins to dissolve even before the show begins. What we see are flashes, but we can’t say whether they are flashes of the human world or the non-human one.

The most visible and, in a way, the most acute collapse ‒ as it remains largely in the realm of language ‒ is observable in two shows: Tokyo Notes (dir. Hirata Oriza) and Spirits Plays (dir. Sato Makoto). Tokyo Notes is a projection of the future: Europe is being torn by a war that persistently recurs in the characters’ lines. Putin is 82 and still ruling Russia, volunteers are enlisting to fight, anti-war protests are mentioned, European works of art have been whisked off to Japan to protect them from destruction (as if this was the worst thing that could happen during a war). In the museum where the play is set, snippets of conversation are heard. They reference family problems, enlisting, inheritance tax, a past love affair between a schoolgirl and her teacher, a refugee crisis, change of nationality and Vermeer’s painting. Each of these topics is discussed in a different language (Japanese, Chinese, Thai, English, Tagalog, Russian, Korean, perhaps more). This extraordinary soundscape is virtually impossible to decode without captions. But amid this confusion of languages there are moments of residual communication as there happens to be someone else who speaks each of the languages. The momentary joy of the characters when their message gets through and they break free from the closed circle of their own language code does not dispel the specter of war and death. It is as if the war and death were becoming a universal language, one existing beyond cultural divisions. One character says at one point: “We can’t do anything about the war.” But who does the collective subject “we” refer to? People in general? Civilians? Visitors to an exhibition of Flemish painting? The citizens of Japan, the Philippines and Korea?

The characters of Spirits Play, i.e. the souls of those who have died outside their homeland (a general, a mother, a daughter, a soldier), face a similar problem. They are ghosts who cannot find peace after their deaths so they keep roaming the earth. They differ in social status and in the languages they speak, which are determined by theatrical form. The actors follow three different acting styles: Kunqu, Noh, and dance (which appears in the second part of the show). The general’s ghost walks and sings with a throaty voice in keeping with the Noh theater rules, the soldier sings and performs acrobatic feats in line with the principles of the Kungu opera, just like the lamenting mother ‒ all this in accord with the original idioms of the particular artistic forms. The contrasting movements and sounds fill the almost bare stage (containing nothing but chairs and a table, Xiqu-style), at the back of which captions with Japanese, Chinese and English lines are displayed. The characters are enclosed in the same space but the only way they can communicate with each other is through glances. Each character tells their own story. They are driven by diverse values and motivations.

The languages fall apart, intertwine, form a complex web of meanings, each belonging to a different order. The sound of the words and their records, the interplay of the languages, the coexistence of the different theater forms, the interwoven images and the quest for humanity all make us wonder why it is so difficult to communicate. Is nothing left beyond differences and isolation? How to remain human if it is impossible to find a language of humanity? Is this a new Tower of Babel?

InlanDimensions International Art Festival, September 24th –October 19th, 2021, VOD platform, Bridges Foundation

The article was first published in Polish in Didaskalia, No. 166 in December 2021. It was translated by Didaskalia into English for TheTheatreTimes.com. To read the Polish text, click here. Didaskalia is now an open-access journal appearing bimonthly.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Urszula Pysyk.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.