Joe Papp would be proud had he lived to see what his Mobile Theater had become: a brimming, joyous sanctuary of inclusivity and plurality, of Shakespearean excellence armed with subtle and striking mindfulness, no longer a struggling caravan of the American theater’s earliest pioneers, but a rag-tag group of brilliant players all the same.

Now safely at home after its tour through New York City’s five boroughs, the Mobile Unit’s production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream is an explosion of joy and laughter, bewitched by a cast of New Yorkers dedicated to the art of translation, to the task of bringing the wonderful absurdities of Shakespearean comedy to audiences of diverse providence, and the brightest example of The Public Theater’s founding mission.

For those of you who have not had the rare privilege of attending a Mobile Unit production, I beseech thee (we’re doing Shakespeare here) to find your way at least once in its path. Its ancestor is the Mobile Theater, Joe Papp’s first attempt at bringing community-centric, free Shakespeare to New York. In 1957 the theater group toured its first free production of “Romeo and Juliet” across the city, Papp ultimately finding a home for its vision at the Delacorte Theater in Central Park, then inside the old Astor Library. Today, the Mobile Unit serves as the contemporary arm of The Public’s earliest mission, twice a year touring two innovative Shakespeare productions across the city’s five boroughs, in homeless shelters and public libraries, LGBTQ centers, and correctional facilities.

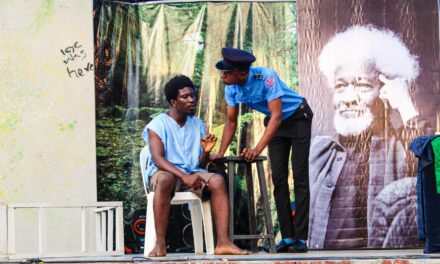

Naturally, the lights stay on inside the Shiva Theatre, The Public’s black box space where A Midsummer Night’s Dream has arrived for its month-long, sit-down run. This is a show meant to be performed in any variety of public space, meant to be packed up in a van and thrust down the Cross Bronx Expressway, hauled by a small cast and production team who carry what they can. Here, even inside The Public Theater’s bones, we’ll watch in full daylight.

The wooded forest of fairy King Oberon is colorful, bouncing New York block party, its inhabitants not young Athenians, but the sons and daughters of a vibrant concrete jungle, bumping along to Beyonce on a boombox. Queer, black, latino, white, young, old. The actors mingle with the audience — but this is no in-character, cliche director’s party trick. They ask how your day was. Talk about the weather. Chit-chat. Some friends of the cast showed up to the performance I attended, and they stood to hug and dance and laugh and wish the production well.

Still, this is a forest block-party inhabited by fairies, mischievous arbiters of magic determined to show us, mere mortals, that we’re fools. And the real magic happens when the dancing and the laughing, the chatting and the celebration, settles almost imperceptibly, as if you’d slowly, carefully turned down the volume, into the cradle of Shakespearean prose.

Technically, this is a bare-bones production, confined to a small, center square. But director Jenny Koons’ (Burn All Night) agile cast fills this stage with an energy and richness able to occupy any amphitheater. As Puck, the mischievous fairy-jester whose own playfulness wreaks havoc on the forest’s lovers, Natalie Woolams-Torres (Tiny Beautiful Things) is a stand-out performer whose radiance is a perfect match for any Mobile Unit production. The same goes for David Ryan Smith (One Man, Two Guvnors), a seasoned Shakespearean actor who, as Egeus and Quince, elevates this production. Christopher Ryan Grant (The Iceman Cometh), even after so many have played the legendary ass ad infinitum, may just be the funniest Bottom I’ve ever seen.

And the laughter is something to take away. People go to the theater and laugh at comedies all the time. “Uproarious” is a common term. But it’s rare that audiences laugh comfortably, without inhibition or an awareness of the proscenium before them. Maybe the Mobile Unit’s greatest innovation, fully on display with A Midsummer Night’s Dream, is its mission to create open, free spaces for a theatrical experience. Beginning to end, Jenny Koons’ staging purposefully breaks the barrier between actor and audience, such that the actors’ expectation is not one to draw their audience deep into some profound piece of theater; nor is it the audiences’ to lose themselves in some rapturous experience. Instead, by blurring the boundary between actor and audience, space and occasion, the expectation, on everyone’s part, is to simply enjoy a great performance. And that’s how you get people to really laugh.

Yet, beyond silliness, Jenny Koons and her cast have achieved something a great deal more. However loud the audience’s laughter may be, it rises literally below the dreams of all who have touched this production.

As the cast and crew have traveled throughout New York City, they’ve asked audience members to write their answer to the question “what do you dream of?” on a small pennant — because, fundamentally, this is a show about dreams, about waking up and finding your life, the world, unrecognizable. During each performance, the cast strings these pennants above the audience, hoisting the dreams of all who’ve answered their question.

Surely, of what we’ve dreamt may be scary. In creating an open space, we let the outside come in. This is a hilarious production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, but it’s also acutely aware. One of the characters wears a “Dump Trump” pin, another the pride flag. In her program notes, Stephanie Ybarra, The Public’s Director of Special Artistic Projects, writes: “so much of this play’s journey resonates with the fact that, as I type this in September, we are careening toward the midterm elections and collectively wondering: What awaits us come November 7?”

These are small gestures, hidden in a joyous production; still, placed carefully amidst a piece of Shakespeare meant to question dreams gone array, they carry a heavy burden, imploring us to ask ourselves how, when we sleep again, we might dream for a different morning.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Michael Appler.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.