As participatory theatre saturates the mainstream, here’s Persis Jade Maravala and Jorge Lopes Ramos on why performing in immersive theatre is a skill that can, and must, be taught.

Immersive experiences have become almost as ubiquitous in the UK as Cafés with Wi-Fi, or Craft Beer. Since this trend has emerged from the early work of a handful of theatre companies a decade or so ago, the majority of makers and presenters of this work today have come from the performing arts industry. The problem? Conventional actor training, which still forms most of the training available to actors in formal education in the UK, does not provide actors with an awareness of a live audience that might be invited to participate. The same goes for the existing training available to directors, choreographers and writers who want to devise new work to immerse audiences in. Might courses for actors, writers and directors consider skills in game-design, digital interfaces, conflict resolution?

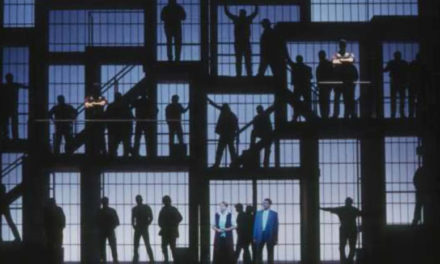

The term ‘immersive’ is deeply problematic, as it doesn’t describe the quality, craft or care necessary to create a meaningful interactive or participatory artwork. More often than not, the term is used in marketing materials to sell an ‘experience’ that involves a combination of site-responsive or designed installations which audiences are invited to explore, usually including some form of close proximity to performers. The supposed freedom offered to audience members, or the ability to interact directly with the fictional scenario in question, raises a number of issues. The skill and experience required by makers to design such logistics, and for performers to manage active audiences in the context of such a proposition, would benefit from more rigorous investigation and care. We must not underestimate the importance for actors to refine a nuanced performance ‘tone’, and how to observe and listen to audiences. It is this thoughtfulness in approach that we believe can, and must, be taught.

Those who, through years of practice, understand how problematic the term immersive can be, must take responsibility for mentoring responsible and rigorous performers and practitioners to encourage excellent artistic practice, particularly in interactive projects. Because if we don’t, no one else will. We must be more than just role models for ethical and responsible practice. As practitioners, we must share our methodologies. We should clearly articulate to audiences, funders, festivals and especially to artists committed to making such work, just how time consuming, expensive and complex a process of creating extraordinary experiences for active audiences is – especially when audiences are invited to interact. What we widely understand as immersive theatre today is influenced by early productions that achieved overwhelming success with both public and critics. However, these productions did not achieve such praise for being immersive per se. Instead, the depth of experience for their audiences was a direct result of precisely how, and why, they were invited to participate in the first place.

Whilst writing new training approaches for actors in the Hotel Medea overnight trilogy (2006-2012), we stumbled upon numerous challenges. Professional actors are not trained to manage audience participation. They are trained to act. And regardless of how good they are at doing it, their skills are specific to a form of theatre which does not include intimate relationships with audience members. Therefore, when confronted with individual audience responses, actors may not possess the skills required to handle unexpected and nuanced reactions. Most of the key moments in the Hotel Medea trilogy became very problematic for actors to negotiate, as they needed to sustain their pre-defined fictional role, whilst encouraging individual audiences to role-play, both managed with a subtle performance ‘tone’ which would not patronize or alienate audience members. Other issues we encountered in early iterations of our work resulted from actors that were too keen to get audiences involved. Less experienced members of the cast, whilst performing fictional roles, at times tried to coerce audiences to join in, creating the opposite effect for audiences. Without the appropriate training, actors also misjudged the ‘tone’ of their acting whilst putting audiences to sleep at 2am. This was a delicate moment in the narrative where the maids (played by actors) were in charge of Medea’s children (played by the audience). In the early iterations of the production audience members were at risk of feeling patronized by actors if their performance ‘tone’ was too forceful although eventually, this turned out to be one of the most successful and memorable moments of the overnight trilogy.

Theatrical events that propose active exchanges with the audience are often less aligned to a literary culture and operate in a similar way to non-literary events such as sports contests or other cultural performances such as processions, parades and role-play games. For us at ZU-UK, the unspoken contract between audience and actor is at the very core of any theatrical event, whether or not it ends up being interactive. Our creative process is driven by strong ideas, whether or not they are considered ‘art’. We have never set out to make an immersive event. Neither did we decide our work should be participatory or indeed interactive. However, since our inception, we have been obsessed with the role of individual audience members within the theatrical dramaturgy. This, in turn, led us to also question the role of the actor and the role of our chosen site in relation to the event.

We have since redefined the terms we use to describe actor (host) and audience (guest) to describe those who perform and those who are invited to attend our events. We have also consolidated a ‘Dramaturgy of Participation’, articulating and disseminating different approaches we apply when making new work, including Participatory Rituals, Immersive Environments, and Interactive Game-Play. Although we would all like to believe audiences are ‘immersed’ in our work, we rarely consider the behavior we are encouraging in audiences. For instance, are we encouraging audiences to compete with each other for intimate VIP experiences, or are inspiring them to form new temporary communities with their fellow audience members? Are they asked to stay silent, or are they challenged to take a stance? Do we invite them to consider uncomfortable ideas through humour and play, or do we sell them the most thrilling and entertaining immersive experience we possibly can? As the term ‘immersive’ gets appropriated by corporate events, and as ‘immersive’ practitioners seek business models which include a large number of audience members per night, some of the most problematic ethical issues mentioned earlier risk being exacerbated. Namely, the encouragement of competition between audiences and the lack of care when creating and managing audience participation.

This year we have started to pilot a series of experimental workshops at GAS Station to focus on interactive technology and intimate performance as creative tools for such investigations. We have also partnered with the University of East London to launch a new MA Contemporary Performance Practices based on our research, to ensure best practice for audience participation continues to be developed and shared. Our efforts are merely one of many contributions which are urgently needed in order for a wider ecology of responsible practice to be encouraged. We hope the launch of such projects inspires our contemporaries to articulate and contribute approaches, tools and methods which can create a positive impact across Higher Education and emergent practice.

‘Immersive’ (whatever one means by it) has clearly entered the mainstream and changed the way we experience theatre forever, but it is more important to continue the pursuit of excellent artistic experiences whether they are tagged as immersive or not. We hope to hear from similarly minded practitioners and researchers in order to strengthen networks and contribute to a more daring yet responsible field.

Persis Jade Maravala and Jorge Lopes Ramos are the creators of ZU-UK and GAS station. For more information on their work, visit their website here.

This article was originally published on Exeunt Magazine. Reposted with permission. Read the original article.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Persis Jade Maravala and Jorge Lopes Ramos - Exeunt Magazine.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.