The playwright explores issues that plague Kenya today and he does that with a compassionate eye and a ruthless tongue.

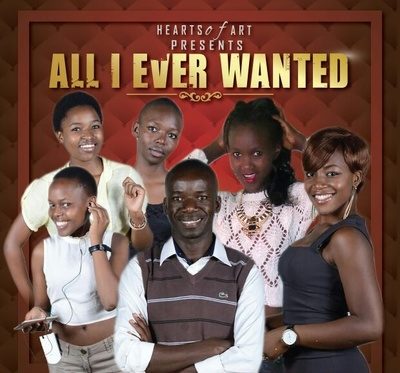

[Remarks by Paul Kihara Kariuki, President of the Court of Appeal of Kenya, at the first performance of All I Ever Wanted, a play by Walter Sitati on Saturday 23 April, 2016 at the Alliance Francaise Auditorium, Nairobi]

Kenya’s creative economy has always depended on brave hearts like Walter Sitati; on people who use the few resources around them to build a home of creativity for themselves and others. When I look back, briefly, at the history of theatre in Kenya – from Donovan Maule to the Mombasa Little Theatre,

The Nakuru Players, Seth Adagala’s National Theatre Drama School, The Phoenix Theatre in the 1970s and 1980s, The University of Nairobi’s Free Travelling Theatre, Wahome Mutahi’s work at Wida Highway Motel in the 1990s, – what I see at the heart of that rush of productivity, is men and women who are distinguished by their selflessness and their dedication to the craft of creativity and performance.

I think that Walter Sitati truly belongs in this pantheon of the makers of Kenya’s theatre arts.

Frankly, I have always had real admiration, maybe even envy, for those who do the kind of work that he does. It takes real ingenuity and raw courage for one to set up a theatre company. I read somewhere that at some point, in his desire to make something new, Sitati called local actors on Facebook to come and audition for his new theatre company. That Facebook call got 700 responses and Sitati patiently organized the auditions so that he could tap into the very best acting talent that was on offer in the country at that time.

Creating a vibrant theatre group like Heart of Arts is an act of selflessness and dogged dedication. And selflessness and dedication are two qualities that we would do well to inscribe in our national values. We need them urgently and we need to be very sincere about this and apply them to the work that each one of us undertakes in every business, every service sector in this country.

There was a time when I was a regular at the Phoenix Theatre – in more than one capacity. I am a little out of touch with the theatre scene today, but whenever I flip through a few TV channels or catch the reviews of plays in the local press, I get the impression that what is now called “the laughter industry” is rather preoccupied with satirizing ethnic accents and exploring the hypocrisies of modern-day romance.

These are worthwhile subjects, I guess, because they do tell us something about the ways in which we judge each other and the places where dishonesty thrives. Still, I feel a little more excited about the prospects of art as a barometer of national values, as an instrument that shapes individual character and national identity when I look at the titles of Walter Sitati’s plays.

- Scars, Saints and Stilettos

- The Other Life

- Sins and Secrets

- All I Ever Wanted

Looking at these titles, I know that Sitati has to be one of Kenya’s most observant social critics – a man who asks the hard, unwanted questions; a gifted wordsmith who sees connections between things that the rest of us might not recognize as important or related. His work brings to mind these eternal words of the great French Philosopher, Albert Camus, from his enduring novel The Plague:

“… again and again there comes a time in history when the man who dares to say that two and two make four is punished with death. The schoolteacher is well aware of this. And the question is not one of knowing what punishment or reward attends the making of this calculation. The question is one of knowing whether two and two do make four”.

What I have seen today convinces me that Sitati explores issues that plague Kenya today and he does that with a compassionate eye and a ruthless tongue. Sometimes, the reality around us is so fast-paced and so confusing that we really do need the Walter Sitatis around us to break it down in story lines that we can follow in one sitting, and see for ourselves what kind of people we are, and what kind of people we should be if fairness and brotherly love are to become the distinguishing markers of our country.

There are many reasons why, this afternoon, I really enjoyed this play, All I Ever Wanted.

The story line sees right into the hearts of Kenyans. When did we become these selfish people; so driven by instant gratification that keeping the battery on a cell phone alive is more urgent than saving the life of a mother?

When did we become people who know all about our wants and our rights, but who bear very little responsibility for what is happening to others around us; and what we ourselves can do, as individuals, to build a more just society?

Is there a difference between law and justice?

Is forgiveness possible even where justice is absent, or doubtful?

I want to go away thinking a little more about Sitati’s messages of hope for our society because in some ways, he reminds me of the Ghanaian novelist Ayi Kwei Armah. In The Beautiful ones Are Not yet Born, Armah observed with such clarity, what it means to have a conscience and to take on the role of enlightening others and triggering hope and regeneration. His main protagonist – simply known as “the man” – stays the course of his fairly routine life as a railway traffic control clerk. But even at that lowly level, he never veers from the course of what his conscience tells him is wrong, regardless of whether it is being done by high and mighty government ministers or his very ambitious wife, Estelle. He walks while others drive by, fast and furious. And in the end, his caution, his gentle firmness, his kindness combine to provide redemption for both Estelle and the government minister, Joe Koomson. When you observe “the man’s” success in converting Estelle to his way of thinking, you know that there is real hope in the work that thinkers like Walter Sitati undertake. In the words of that great Armah novel,

“Disgust with injustice may sharpen the desire for justice. Readers who don’t see this connection merely wish to be entertained, and I have neither skill nor desire to turn the agony of a people into entertainment.”

All the same, we must never forget to thank Alliance Francaise for the consistency with which they have supported the creative arts in Kenya by providing some space for our entertainment. By providing this rehearsal and performance space, Alliance Francaise stand in the gap of so many things that our creative economy needs. They remind us that entertainment is always an opportunity for reflection and soul-searching. At its best, laughter comes with a few home-truths. This afternoon, we have had a good dose of both, thanks in large measure to the work of Walter Sitati and Alliance Francaise; and thanks, too, to the quality of acting that we have seen on this stage today.

This article was originally posted at Pambazuka.org. Reposted with permission. Read the original article.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Paul Kihara Kariuki.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.