The successful development of new work for the opera stage is a complex and often elusive process. Ask anyone who has contributed to the making of a new opera, and they will tell you there is no single formula that works every time. Composers, librettists, directors, designers, and producers who collaborate on new work must always reinvent the process to suit the unique musical and dramatic needs of the piece they are creating. Increasingly, composers and producers have called on the knowledge and experience of a dramaturg—a knowledgeable theatre practioner—to help give direction to the creative process. Whether one of the central members of the creative team (for example the director) or a freelance consultant, the dramaturg can be anyone who helps guide development by serving as an advocate for the piece and catalyst for collaboration, as well as editor and sounding board for the authors.

Some opera companies North America regularly employ dramaturgs to work on new productions of established operas in the repertory. The dramaturg provides research on the historical and cultural context of the opera, helps in the translation or interpretation of words and music, and works with the director to find ways to transform a classic score into an original stage production. The development of new work is different since the creators are engaged in an ongoing conversation about how to shape a work in progress. But in both cases, the ultimate role of the dramaturg remains the same: to focus on the big picture, to think about the overall structure of the work and to make suggestions that will improve how the piece comes to life on stage.

“The dramaturg can ask the questions that no one else has asked because they are immersed in the process in a very particular way,” said Brian Quirt, former president of the Literary Managers and Dramaturgs of the Americas (LMDA), a service organization with over 500 members from a variety of theatrical and literary backgrounds. “Dramaturgs are different [from the other collaborators] in that their responsibility isn’t to a single aspect of the creation. Whether dealing with text on the page, a musical played at the piano or in action on the stage in front of you, the dramaturg is there to respond to the ideas that are being expressed and to help find the next step in the process.” Quirt works actively as a dramaturg in theater, dance, and opera and he values the creative energy generated by collaboration across the disciplines. “It’s great that we can begin a conversation between people who do this work in the opera world and the theater world,” said Quirt. “The work is similar—we’re both telling stories—but the tools that we use can be somewhat different…It’s the kind of crossover that can be particularly rich and productive.”

Composer Jake Heggie has built close collaborative relationships with artists who have extensive experience in the theater world, including stage directors and playwrights. For Heggie, it is important to have the entire creative team on board from the beginning of the process of writing a new opera, since each collaborator brings a different perspective on how to unlock the theatricality of the story. “As the composer, working from my perspective, you spend so much time alone, and it’s dangerous if you get too close to the show in the wrong way,” said Heggie. “You fall in love with one version of it, or you fall in love with one character, and you want to make sure that everyone gets their due. The dramaturg or director gives me perspective in the same way that the conductor gives me perspective on the score.”

In the case of the opera Dead Man Walking, the director Joe Mantello took on the role of dramaturg during development by asking questions that Heggie and librettist Terrence McNally had not considered, which led to further revisions to the structure of the first act. These changes addressed both large and small aspects of the storytelling, including what Heggie calls the “emotional thread” of the characters—how the background of their individual lives are told and connected to the dramatic action onstage. Other more detailed changes suggested by Mantello were geared toward the goal of clarity for the audience on many levels: making sure the individual words of the libretto would be understood, and that the original set and costume designs would support the dramatic and musical arc of the story. Heggie likes to use workshops to assess the dramaturgical effectiveness of his operas and to open up a dialogue that includes his creative collaborators and the singers who will interpret the opera’s characters. His latest opera, Three Decembers, premiered as Last Acts at Houston Grand Opera in February 2008, directed by Leonard Foglia. The opera, with a libretto by Gene Scheer adapted from a play by McNally, was given a full workshop in December 2007 by San Francisco Opera in preparation for the world premiere production. [The opera was commissioned by HGO in association with San Francisco Opera and Cal Performances.] For Heggie, the workshop was an important final opportunity to confirm that, in his words, “the journey of the piece was clear and balanced among the three characters.”

Workshops can also be important during earlier stages in the genesis of a new work. James Leverett, who teaches dramaturgy and dramatic literature at the Yale School of Drama and the Columbia School of the Arts, has participated in a series of five development workshops with the composer Philip Glass and the director JoAnne Akalaitis, who are creating a new music-theatre piece, The Bacchae, adapted from the ancient Greek play by Euripides. The work was co-commissioned by Stanford University and the Public Theatre/New York Shakespeare Festival and is a hybrid of spoken theater and opera. The creators have used the workshops to look at one particular aspect of the storytelling: the role of the chorus and the many functions it serves in the stage production. Leverett sees the workshop as an important time to refine the piece and increase its chances of reaching its intended audience. “One of the things that a dramaturg does is to serve as a kind of first audience as the work is coming into being, and that includes the work as it is being written,” said Leverett. “We often have to work in such curtailed circumstances—in terms of time and financial resources—that if you have this process by which a director and composer can have an ongoing sounding board, you are actually increasing the work’s likelihood of success on the stage.” In the series of workshops for The Bacchae, Leverett has played an active dramaturgical role from the very beginning. He has supported the creators in the process of setting the text of the large chorus scenes to music, and his feedback has led to cuts and word changes in the translation. Because these text changes have been made on the spot, Glass has been able to respond by recomposing the music in small ways that accommodate the text and “Make it sharper and sharper,” as Leverett said.

Important dramaturgical contributions can be made before composition even begins. The Canadian stage director and dramaturg Kelly Robinson has developed a specific type of workshop that he uses in the early stages of opera development to help composers and librettists reach consensus on the direction and meaning of the story they want to tell. Robinson will lead a workshop of actors who speak the text of the libretto. “With a group of actors, you can immediately change the interpretations, so the composer has a chance to actually hear the text spoken with intention by experts who can quickly change their approach. It becomes a very useful roundtable discussion about meanings,” said Robinson. He has conducted many such workshops at the Banff Centre in order to help composer-librettist teams deal with the dramatic reality of the spoken text before the first note of music has been composed.

In Germany, where extensive workshops of new operas are less common than in North America, some composers collaborate with freelance dramaturgs. The German composer Christian Jost has worked with the American dramaturg Minou Arjomand on several opera projects, including The Arabian Night and Hamlet. For Jost, the collaborative relationship can be very personal, both an intellectual and emotional extension of his own creative work as a composer. “The process of creation is an intimate moment, so talking about it has to do with trust and the thoughts of the other person as well,” said Jost. “It is like performing chamber music: You think similarly and you feel similarly, and in the best case, you have in the opposite person an extension of your own thoughts.” Jost writes his own librettos or adapts existing texts, so his collaborations with Arjomand have focused on the range of source material and sometimes on the structure of the dramatic action. Arjomand has also assisted Jost in working out the unique compositional challenges of adapting sources from both German and English. “Christian and I are similar, and we work so well together because we can appreciate the importance of sitting down and spending time with the book,” said Arjomand. Together they have worked on a range of source material, from texts by the German Romantic poet Friedrich Hölderlin for the choral opera Angst, to the writings of filmmaker Woody Allen for the one-act chamber opera Death Knocks.

Many North American opera producers are seeking to give composers, directors, and dramaturgs adequate time for experimentation and discussion. Music-Theatre Group (MTG) is an organization dedicated specifically to supporting new works from the early stages of the commission, through development, to fully-staged productions. Producing Director Diane Wondisford emphasizes that no two works have the same needs, and that creative teams must be given the necessary time and space before the work is rushed into rehearsal. “It’s an exploration,” said Wondisford, who considers dramaturgy an important part of her role as creative producer. “We’re asking the “who, what, when, where, why” questions about the material for the first time. One has to be acute and rigorous in the process, and it requires that all of the collaborators share the discoveries each step of the way.” In fostering new work, Wondisford has also shown a commitment to bringing together creative teams of composers and writers who do not write primarily for the music-theater with experienced stage directors who assume the role of dramaturg during the development process. This was the case for the team behind the jazz-opera Running Man, the first of several stage collaborations for stage director Diane Paulus, the jazz composer Diedre Murray and the poet Cornelius Eady.

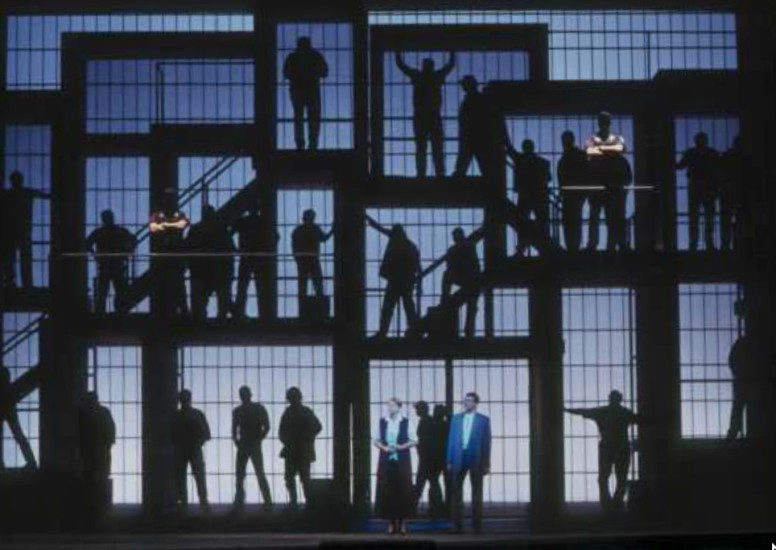

Music-Theatre Group and the MIT Media Lab are currently developing a new opera entitled Death And The Powers, which will have its world premiere in Monte Carlo before going on a world tour, beginning with performances at Montclair State University and Chicago Opera Theater. Composer Tod Machover enlisted former U.S. poet laureate, Robert Pinsky, to write the libretto. The collaborative team also includes Randy Weiner, who co-authored the story with Pinsky, director Paulus, production designer Alex McDowell and a team of robot, content and technology designers from the MIT Media Lab. The project employs cutting-edge music and stage technology to tell the story of one man’s life and his attempt to overcome death. Even for an opera that is so avant-garde in musical language and stage technology, much of the dramaturgical inspiration behind the structure of Death And The Powers came from working with theatrical texts of the past, in particular, the plays Oedipus At Colonus and King Lear. “There are very few operas, even the great masterpieces, that are wholly original,” said Paulus. “I am a great believer that when you are making something new, you are also looking back at older models and stories. The hidden dramaturg in the room is the great theatrical literature of the past that you look at and consult.” Paulus emphasizes that the top priority in development is working out the right structure for the piece as a whole — the spine underneath the words, music and production technology. The creators of Death And The Powers drew upon these classic plays to help forge complex relationships between characters. From the structure of Oedipus At Colonus, the team found a model for their meditation on death, and King Lear provided additional material for the way that the final chapter of life can bring out tensions within a family. Ultimately, the team found their own original perspective on these central themes, but only after a long period of experimentation in which these models provided important dramaturgical inspiration.

The future holds much potential for new directions in the creation and development of new works, especially with collaborations at the institutional level between opera and theater producers. The Metropolitan Opera and Lincoln Center Theater are charting new territory in their partnership to co-commission new works. By working together, the organizations hope to provide more resources and flexibility to composers and playwrights working in various musical and dramatic styles. The collaboration was an initiative of the Met General Manager Peter Gelb and is being managed by the company dramaturg, Paul Cremo. André Bishop, artistic director of Lincoln Center Theater, sees

the partnership between companies—the first sustained collaboration of its kind between two constituents of Lincoln Center—as a joining of forces from which both sides stand to gain. From his extensive experience fostering new plays and musicals, Bishop hopes the new project will give operas more time to develop, even after they have been through an initial round of workshops. He cited the example of the Broadway musical, which traditionally has several weeks or even months of previews and out-of-town tryouts when the creators can make final changes before the official opening. “Part of the problem with new works in the opera world is that there isn’t a lot of rehearsal time,” said Bishop. “For something new, there has got to be more time.” The first collaboration is scheduled to debut in the 2011-2012 season, and new works will then be presented on an annual basis.

Cremo hopes the long-term support will give creative artists greater opportunity to experiment and refine their work both musically and theatrically. The proximity of the two organizations as neighbors at Lincoln Center will facilitate an ongoing development process that combines the best of both worlds. “We’re inventing something new here, to bring together both the theater-based model and the opera-based model,” said Cremo. “Opera boils down to essential emotions that are visceral, and the goal of new work is finding the most sophisticated way to focus those emotions both dramatically and musically.”Whether on the intimate scale of a two-person collaboration or for large-scale projects that bring together the resources of several arts organizations, the dramaturg can be both an active collaborator and a creative inspiration in helping to foster new work of lasting importance.

The original version of this article, “The Role of the Dramaturg in the Creation of New Work” was published in Opera America Magazine, April 1, 2008, and subsequently reprinted in The Routledge Companion to Dramaturgy, 2014. Reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Andrew Eggert.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.