Just as the first signs of autumn begin to take over the glorious summer (shorter sunsets, occasional winds, gradually falling temperature), August in Helsinki offers a treasure of cultural treats for the public as the Helsinki Festival, the biggest cultural event of the Finnish capital, takes place in various locations. Helsinki Festival organizers always aspire to bring in radically different and diverse productions, involving both world-renown Finnish and international artists. Blended in with those special summer evenings and autumn twilight, the memories of this festival stay forever. This year brought many new and different experiences– hearing a choir of robots singing on a city square, spending a night in a tent listening to music specially composed to accompany your sleep cycles or discovering Richard Wagner’s Ring of Nibelungs through the eyes of children.

One of the highlights of the Festival belonged to a traditional genre – classical music – but was no less fantastic or expected by the audiences than more experimental events. In August 2019, Susanna Mälkki, an extraordinary conductor who has appeared in world concert halls, including locations like LA, London, and Paris, took on a demanding piece for a male choir, a mixed choir, soloists, expanded orchestra and a narrator – Arnold Schoenberg’s Gurrelieder. This cantata is rarely performed, as it requires a large orchestra, a huge choir, and significant skill and concentration from all involved, including the conductor who has to manage the arranged musicians and singers. However, neither Mälkki, nor her performers – Simon O’Neill, Emily Magee (and others), Helsinki Philharmonic Orchestra and the Lahti Symphony Orchestra – were strangers to such a demanding piece.

Gurrelieder (1900-1910) is a rarity that takes its roots in the romanticism 19th century while having been composed in the 20th. The work is based on the collection of poems by Jens Peter Jacobsen who used the Danish folk story of tragic events involving King Valdemar (Waldemar in German), his mistress Tove and Queen Helvig (Waldemar’s wife, Waldtaube in the score) who kills Tove out of jealousy. Schoenberg worked on the piece throughout a decade, while developing as a composer and almost leaving his romantic inclinations behind him. Influences of both Wagner and Mahler are felt in the piece, while the introduction of Sprechgesang (a recitative, singing resembling speech) is a harbinger of his own future work Pierrot Lunaire (1912). The history of its creation reflects the eclectic result, as its three parts are off-balance and are different in their usage of choirs, singers and the orchestra. The task of the conductor is to give the whole composition a unifying thread and present the development of the drama while highlighting drastically different moments of romantic love, tragic death, a devilish hunt, a grotesque, plaintive song of jester Klaus, and a culminating scene of the rising sun.

Susanna Mälkki, through intensive rehearsals and separate work with the soloists, choirs, and orchestra, was fully prepared to lead us through this tale, help us process a difficult German text and appreciate different orchestral decisions and beauty of particular moments of Schoenberg’s score. She was also attentive to her soloists – magnificent Wagnerian Simon O’Neill (Waldemar), Emily Magee (Tove), Katarina Karnéus (Waldtaube), Wolfgang Ablinger-Sperrhacke, who had already sung the same role in London a year ago (Klaus Narr), Gidon Saks (Peasant) and Salome Kramer (Narrator). Although not all parts were equal in size, brief appearances in such roles as Klaus Narr and Narrator gave audiences a surprise and spurred this fantastic work further. The conductor also didn’t forget about her choir and kept a nice balance between it and her singers which allowed the latter to be supported by the background screen of sound that was incorporated into their individual storylines. Mälkki who is always rigorously attentive to detail, also masterfully created Schoenberg’s orchestral tableaux through constant shifts of attention to each instrument, which and was hellishly difficult, taking into an account the number of musicians involved. It was a memorable evening deserving a standing ovation, and one of the rare Gurrelieder to be heard.

Another production of the Helsinki Festival, no less ambitious in scale and preparation, was also a work that it is rarely performed – Robert Schumann’s oratorio Scenes from Goethe’s Faust (1844-1853). Shuman started the composition a decade after the death of Goethe, whose Faust he used as the text for this dramatic work. He used both Parts 1 and 2, choosing specific scenes from both texts, and, interestingly, in the final scenes of Faust’s Transfiguration, he incorporated the same text in his composition that Mahler would use for his 8th Symphony. Like Gurrelieder, Faust consists of three parts, is similarly eclectic and it depicts a tragic story of love and redemption. They are both romantic works, but Faust has a more well-known source and philosophies of personal enlightenment and searches for truth running as its core theme. The score has multiple parts for singers, but in this production, each soloist took on several parts. Extraordinary vocalists took part in the performance: Soile Isokoski (Gretchen), Arttu Kataja (Faust), Markus Suihkonen (Mephistopheles), Helena Juntunen (Magna Peccatrix) and others. Several choirs – Tapiola Chamber Choir, Emo Ensemble, and Cantores Minores, as well as Finnish Radio Symphony, were involved in the performance. The conductor Hannu Lintu patiently and skillfully organized the musicians, through rehearsals in the building of the former Cable Factory, in a way that was attentive to the thread of the story and to the unity of orchestral-vocal-choral expression.

Faust. Helsinki Festival, 2019. Photo: Petri Antilla.

If that combination of powers was not enough, the performance was taken to a mixed-genre level by the introduction of a separate, intricately weaved, video story (shown on a large screen behind the orchestra and below the choir, seated in the top gallery). It also had a theatre pantomime, involving actors featured in the video, and the story switched back and forth from video screen to real life. As envisaged by the director Jussi Nikkilä, the theatre/film part of the performance tells the story of a famous artist (Hannu Kivoja) who is tormented by memories and crisis when a Mephistopheles (Sanna-Kaisa Palo) visits him and a journey (involving a taxi ride to the Cable factory where our evening takes place) begins. Through inventive storytelling, Faust is confronted by images of Gretchen (Alise Polacenko) in love with his younger self (Tom Rejström), and follows them through their love, partly remembering it, partly wishing to embody himself in the past and start things all over again. There are images of a drowned child and images of Faust’s suicide in the same lake. Later he is flown through beautiful Nordic imagery to a certain location where he meets everyone he had ever loved and cared for and sees his life filmed back to him. The incredibly inventive cinematography by Raimo Uunila stole the attention of the public, while changes of lighting (Pietu Pietiäinen) distracted our focus from the acting and singing. However, this eclecticism allowed us to see the potential of Goethe’s work to carry a modern message. It was an honest exploration of our conscience, guilt, and hope of eternal love and compassion still allowed to us by fate and heavenly forces. To emphasize the redemptive and benevolent end of the oratorio, conductor Hannu Lintu and the soloists reappeared clad in white after the interval. In Part Three, the music soared to heavenly heights, while Faust, in a video story, searched for peace and forgiveness. This was an evening to take in, to contemplate, to be shocked and surprised by, and of course to remember.

Another interesting show that crossed the boundaries of genre, and experimentally presented us with the material we know inside out, was Children’s Ring that came directly from Bayreuth Festival where it had a huge success in 2018. The concept, created by Bayreuth Festival director Katharina Wagner with Markus Latsch, envisions to help children learn the whole Ring story in two hours. That sounds impossible, but the story was stripped of philosophical undertones and ‘the adult’ moments of passion, incest, and revenge. Instead, it was toned down to a fairy tale involving giants, a family of gods (that looked rather domesticated) and dwarves (that is Nibelungs, but it was hard to guess it) that made their lives complicated. The story was told to kids in Finnish (with Swedish subtitles), and while the musical accompaniment (and unfortunately in this concept, Wagner’s music was reduced to that) was performed by the Helsinki Chamber orchestra conducted by Chloé Dufresne. David Merz directed, staging (a simple, but inventive set involving some interesting transformations) was done by Julius Theodor Semmelmann, and the dramaturgy was done by Ruth Asralda. In Finland, this transferred production was produced by Teatro Productions Oy, with Ina Hukki as the director’s assistant.

Children’s Ring. Helsinki Festival, 2019. Photo: Nawrath Presse.

The production was successful with children, who reacted actively and eagerly. Occasionally, they got to interacted with the singers/performers as they invited them to make the decisions with them. From the subjective view of a foreigner, I was impressed that all the kids understood so many complicated lines in Finnish. They enjoyed the challenge and did not mind the intricacies of Wagner’s librettos being interpreted as a strange mix between Brothers Grimm and Charles Perrault with castles, abductions, fights, a golden ring (obviously) and a slight lack of princesses to save. They also did not mind the Helsinki Chamber Orchestra tentatively producing some Wagnerian leitmotifs and then silencing itself for long periods that did not involve singing, (although it is hard to fathom how that is possible in such a short transposition of the tetralogy). They did not notice how lopsided the show was, with Das Rheingold and Siegfried given more attention (their plots were the easiest for children’s minds) and Die Walküre and Die Götterdämmerung cut disproportionately. The singers involved in the production were also uneven, and some of them, like Brünhilde, were stripped of almost every famous line. It was even more paradoxical to watch after attending rehearsals for the ‘real’ Das Rheingold that was simultaneously taking place at the Finnish Opera House. It was an excellent idea but could have been done with much more nuance and attention to staging, text, and music.

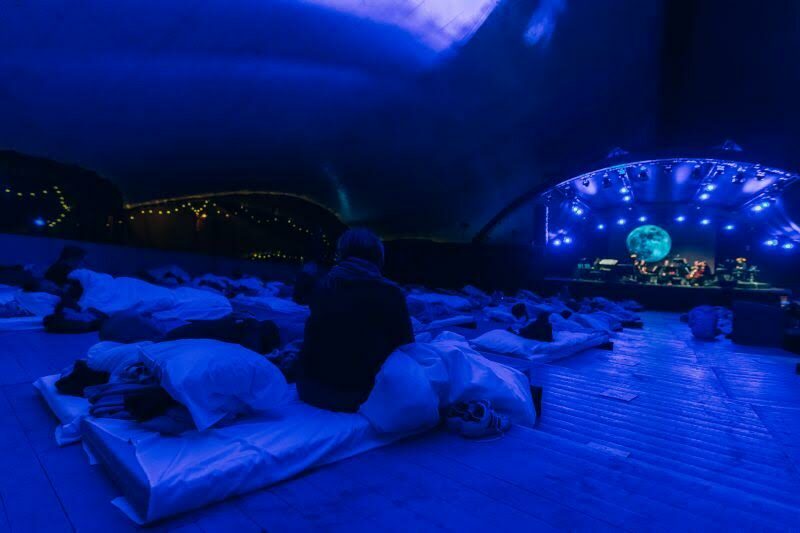

Finally, the last unusual show was a huge, sold-out event for the Helsinki Festival 2019. It was so unique, it left indelible traces in the minds and subconscious of everyone who was lucky to attend it. Max Richter’s phenomenal project SLEEP has been traveling the world since its first performance in London where it set the Guinness World Record. Richter organized his score in a way that it follows the stages of human sleep, including deep and REM sleep. It allows the audience to actually go through the stages, to lie awake and listen or to combine both of these strategies (which I did, trying to stay awake as much as possible). The music was performed by the Max Richter Ensemble (Natalie Bonner and Louisa Fuller on two violins, Ian Burdge and Chris Worsey on two cellos, Nick Barr on viola, Andrew Skeet on keyboard, Katherine Tinker on piano, with Grace Davidson singing some incredibly eerie successions of notes for soprano) in Hüvila tent near the Töölö lake. Some members of the audience were placed on nice, comfortable beds inside the tent itself (about 100 hundred people), while some were listening to music through sound amplifiers from their own individual tents outside. I suspect it could be heard from a tent even in the nearby park.

Sleep. Helsinki Festival, 2019. Photo: Petri Antilla.

This night is very difficult to relate in words, as the experience transgresses any previous experience of being at a concert (classical or not). The music is consciously minimalist and what we expect from Max Richter. It has a “plot,” with music that invites us to sleep at the start and awakens us with the final Dream O movement, and some beautiful and almost surreal vocal lines included in the score. It sets your brain on an 8.5 hours journey inside itself, and thus this experience resembles a night spent on an island, or in meditation or even a session of group therapy. You are on your own and yet amongst people, you sleep and you are awake, you listen to music but it also invites you to have your own dreams, thoughts, and visions. I felt that my inner concentration of the ability to feel love and on the validity of love for my human body became the center of my attention for this night. I fell into some wells of sleep and re-awakened to understand that my brain work has never stopped. For others, this meditation and this night could have been about something else, but what Max Richter’s music does is invite you to look inside yourself and understand the complexity of your own brain mechanisms. After you walk home (and you are given a newspaper to read at 7 am in the morning), you cannot describe the experience with words like ‘good’, ‘bad’, ‘excellent’, ‘fantastic’ because the complexity of this lived SLEEP night goes beyond it, as you face your own fears, hidden memories, hopes or obsessions. It becomes a night lived as though you and music had become one moving and thinking body. The score becomes part of your natural habitat and as other human beings are sharing this with you, everyone becomes co-creators of this event. Time does not lapse and does not pass in SLEEP, it does something else – it jumps, it bounces, it becomes still or protracted, but it relentlessly and powerfully goes on. We are different people than we were when we entered the tent. It was a transformative experience that made the Helsinki Festival 2019 absolutely unforgettable and made us anticipate its next installment in August 2020 that will hopefully be just as extraordinary.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Yulia Savikovskaya.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.