While most scholars addressing issues of feminism in opera focus on the fate of women in opera plots, Boston-based MetroWest Opera has been addressing another issue since its inception, and is now doing so more overtly with La Femme bohème; an all-female version of the original first performed in Austin, Texas.

The company has long strived to produce operas that feature parity in male and female roles, but has mostly run out of this repertoire. Part of this commitment to parity is that the audition lists are overly saturated with female talent. Just as Hollywood is being confronted in media about their lack of female parts and directorial roles, opera too has a long history of casts made up predominantly men. MetroWest’s auditions for this production were open to anyone who identifies as female.

In Puccini’s La bohème, Rodolfo, a poet and Mimi, a seamstress, fall in love and move into his garret apartment together, only to be torn by Rodolfo’s seeming jealousy. Rodolfo confides to his friend Marcello that he’s not jealous, but terrified that his poverty is leading Mimi to an untimely death. They decide to part and ultimately, Mimi succumbs to her tuberculosis, but not before she and Rodolfo and his friends have the chance to reunite. So, while Mimi still dies at the end of Puccini’s most famous opera La bohème, MetroWest Opera has cast a fantastic group of female voices, and the production itself made some apt comparisons between Bohemians living in Paris and artists in Trump’s America.

Saturday’s matinee at the Mosesian Arts Center in Watertown was well attended in a black box theatre seating approximately 80 people. The evening show, featuring a different cast of leads was already sold out as of that afternoon. A piano, cello, violin, and clarinet made up the chamber orchestra which was placed in the corner near the entrance. Conductor, Ng Tian Hui and the orchestra were placed fairly far off center stage, making it a challenge at times for the singers to see him, but overall the ensemble was fairly smooth.

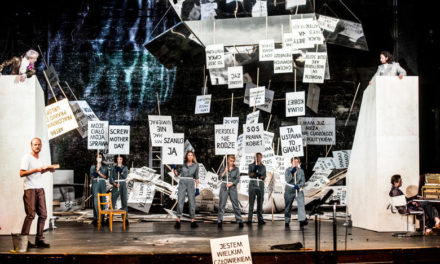

Posters with protest messages denoted a rally/sit-in in the vein of Occupy Wall Street or The Women’s March on Washington. Set pieces, largely the signs themselves, were wild and colorful, and the lighting was moody, both designed by Charles Ogilvie. Cast members wore modern street clothes, some of them in pink “pussy” hats from anti-Trump protests. Marcello, instead of working on paintings, is creating graphics for posters. Colline’s first line at his entrance “The signs of the apocalypse are upon us already” was oddly appropriate from a far-left perspective in Trump’s America. Several tweaks were made to the supertitles to accommodate changes in gender and politics in the libretto but they were mostly accurate to the original. Hilariously, no changes to the Italian libretto were necessary in Act 1 when Rodolfo is appropriately writing an article for “The Beaver.”

There was a reference in the supertitles to the neighbourhood of the café in Act 2 being set in Jamaica Plain. This neighbourhood of Boston is not only known for having a largely liberal population, but also as having a large lesbian population, making it very appropriate for the setting of this piece. Arguably, for La femme bohème, one can choose to have the characters in drag or to have them all playing women, as Director Julia Mintzer did, in female romantic relationships. One can easily imagine these mass groups of women and millennials in this setting. The most obvious connection of this production is to RENT, but there are some distinctions. In RENT, the threat of the AIDS epidemic still can end the lives of even the young people who have abandoned their cushy suburban upbringings. In this era, we see Mimi as a struggling freelancer without healthcare or insurance, who may have no other options, and unfortunately, it could become plausible. Like the original characters of Paris’s left bank, these characters are predictive of people who could have no safety net.

La Femme bohème.Photo: CoCo Boardman

Mintzer’s direction was engaging overall and often original. They managed to fit in a chorus of 23 singers instead of making a common musical cut, so they became as much a part of the set as anything else. The chorus action was borderline distracting from the drama between the leads in Act 2, but a high point included when Parpignol, the clown, unexpectedly rode through space on a bicycle, re-imagined as a courier. There were a few small issues of moments in staging. Mimi ascended a ladder in the middle of her first aria, which became distracting during the most important musical pause in “Mi chamano Mimi,” (arguably, the most important musical pause in all of opera) because it really seemed precarious and unsafe. Mintzer took a risk having Rodolfo interrupt her with a kiss before the final recitative-like section of her aria, but it paid off and pointed to a strong chemistry between the characters who just met. Similarly, Mimi seeming skeptical and a bit more world-wise in this version somehow made their falling in love so quickly more realistic (a perennial problem of suspension of disbelief with the piece).

The unconventional use of English dialogue mostly worked well throughout. Alcindora made a phone call in spoken English in the middle of the sextet after Musetta’s aria and since it was the first use of English, it was a bit jarring. But in one instance where it was put to good use, Marcello and Musetta, instead of screaming at each other in Italian, had some rather colorful turns of phrase to sling at one another at the end of Act 3. Instead of “Viper,” for example, Marcello calls Musetta a “Gold-digging pop tart.” In Act 4, Colline makes two calls to 911 in English, and the first appeared too early into Act 4 and took away a bit of realism. Since there was still a half an hour of the Act left, one is left wondering what happened to that ambulance they called. The timing of the second call on its own would have been sufficient to place Mimi’s decline in our era. Rodolfo’s desperate dialogue at the finale when he doesn’t yet realize Mimi is dead was also translated into English and they wisely omitted Marcello’s famous “Corragio!” line. Finding a contemporary vernacular phrase to replace that would have been challenging.

Schaunard’s staging in Act 4 could have been more impactful. There is a reason Schaunard is the first to see Mimi pass. In Acts 1 and 2, (s)he is not emotionally involved, watching with humor on the sidelines, and in Act 4 she should be watching Mimi intently, not leaving her side and showing just how much this turn of events has changed her character. That is why Colline asks her to leave the lovers alone for a moment. The second half of her line “Fra mezz’ora è morta,” (“In a half hour, she’ll be dead”), was sung facing upstage, which took away the huge emotional impact that the moment should have, the finality of the realization stunning even her as she is saying it, almost to herself. In this production, Schaunard just happens to notice that Mimi might have passed instead of guarding her devotedly, taking a dimension away from her development through the piece.

Musically, listening to women sing in men’s roles was interesting and even more interesting because, after a few minutes, one forgot about the difference in voice and texture. A few choral moments highlighted the women singing in octaves in a strange way that reminded the listener of the difference. The female voice highlighted some musical moments for Rodolfa, in particular. In a woman’s range, there are opportunities to float high notes that are simply not possible in the tenor range. The notes leading up to the high C in his aria, “Che Gelida Manina,” were particularly striking in their tenderness.

Celeste Godin was an impressive Rodolfo. She has a classic Puccini spinto quality voice; a steely sound without being strident. Costume designer Evelyn Quinn crafted an alternative look for her, dark lipstick and fishnet tights, which cultivated the character as the primary artist of the piece. She was strangely facing upstage for her final cries over Mimi’s body, but her voice and despondency cut through the heart strings regardless.

Kelley Hollis’s Mimi was well-acted and beautifully sung, particularly when she bloomed into the singing in Act 3. The top of the voice was simply round and stunning in its crescendo as the show went on. This Mimi started out pretty ill, and Hollis perfected a terrifying-sounding wheeze.

It’s always interesting to see how the men of La bohème have bonded onstage throughout the rehearsal process and with all women, it was no less so. Lindsay Conrad as “Marcella” was the dramatic lynchpin in the comradery between the characters, with a sincere laugh through any awkward extended moments of horsing around. Possessing a surprising lower register for a soprano, she was also an extremely empathetic Act 3 Marcello, listening to her friends’ relationship woes. Rarely has a baritone been given the permission in this historical piece to be so demonstrative with his friends, and it made it all the more poignant.

Conrad and Kristina Bachrach as Musetta clearly had a lot of fun together, mounting their romantic tensions to a great climax of sparring in Act 3. Bachrach’s Musetta was imagined as a gypsy-like Indie pop star surrounded by adoring fans with selfie sticks clamoring to capture her public display on social media. Her aria “Quando m’en vo” was quite choreographed in the way that someone who is being watched by paparazzi would be, and Bachrach delivered with stylized, larger-than-life gestures and a large, cutting voice that commanded attention.

Carrie Reid-Knox gave a stirring, unusually emotional rendition of Colline’s famous coat aria, “Vecchia Zimarra senti,” normally a more stoic goodbye. In this, it was clear that it was more a goodbye to Mimi.

Like much of the stage direction, MetroWest’s La Femme bohème was a departure for the company, whose past endeavors included more standard repertoire. The reward was a highly energetic, fascinating production.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Katrina Holden-Buckley.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.