To probe the practices of both protest and theatre-making, Teatr Polski of Bydgoszcz looked to Revolutionary France with its Stateswomen, Sluts Of The Revolution, Or The Learned Ladies. The 2016 show, presented at December’s Divine Comedy festival in Kraków, centered around the story of Anne-Josèphe Theroigne de Merincourt—an early, and lesser-known organizer of the rebellion that would topple the French monarchy. Directed by Witkor Rubin, the production featured text, dramaturgy, and costume design by Jolanta Janiczak.

From Stateswomen, Sluts Of The Revolution, Or The Learned Ladies (Żony stanu, dziwki rewolucji, a może i uczone białogłowy); text, dramaturgy, and costume design by Jolanta Janiczak; directed by Wiktor Rubin. Teatr Polski Bydgoszcz, 2016. Photo credit: Monika Stolarska

As audiences entered the Stary Teatr’s main space, they encountered Sonia Roszczuk, who stood on a row of seats, dressed in a bright-red coat. Against the bluish-gray walls of the theatre, her image recalled the painting that in part inspired the show—Eugène Delacroix’s 1830 Liberty Leading The People. In it, a woman, with a French flag raised high over her head, leads a crowd of men across the aftermath of the July Revolution. Roszczuk’s accessory, on the other hand—an open umbrella—evoked the more recent events of “Black Monday,” the large-scale Polish women’s strike that in October 2016 pushed back on a proposed total ban on abortion. Inspired by a landmark 1976 Icelandic women’s strike, the movement has since sparked continued feminist protests across the country, as well as sister marches around the world.

Stateswomen’s ensemble, of six women and five men, sketched out de Mericourt’s story through deft descriptions of an imagined book of her drawings—her early life, her training as an opera singer, her Revolutionary speeches. The tone of Janiczak’s richly layered text allowed it all to live simultaneously in the past and present—its Danton, for example, was Gérard Depardieu in Andrzej Wajda’s 1983 film of the same title. He also evoked certain more contemporary politicians, as he and his pal Robespierre mansplained revolution to a group of women—who had just pulled off the March on Versailles.

From Stateswomen, Sluts Of The Revolution, Or The Learned Ladies (Żony stanu, dziwki rewolucji, a może i uczone białogłowy); text, dramaturgy, and costume design by Jolanta Janiczak; directed by Wiktor Rubin. Teatr Polski Bydgoszcz, 2016. Photo credit: Monika Stolarska

At the same time, Stateswomen teased out problems inherent to the process of theatre, as they likened the imagination and finesse it requires to any other kind of insurrection. De Merincourt’s role, which felt warmly natural for Beata Bandurska, became like a director, at times evoking the meta-perspective and pleasure of Peter Weiss’s play Marat/Sade. As she passed out pamphlets or instructed us to link hands with our neighbors, we accepted her as our leader, too. “You wouldn’t cancel the performance!”—this performance—another actress protested at one point. No—she wouldn’t put down the mirror that she and the show held up.

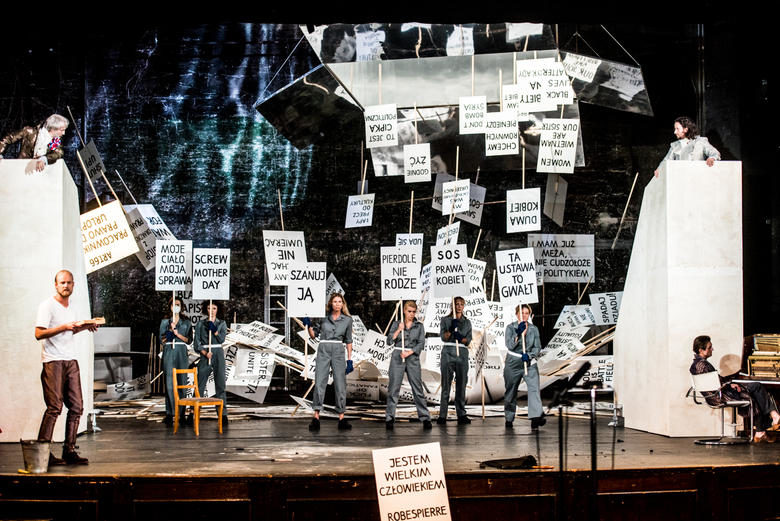

We learn that the real de Merincourt, a Girondist, was later attacked by a mob of Jacobin women—not unlike the ensemble that surrounded her now—which landed her in a mental institution. We feel almost accountable—after all, no one had answered her plea to even just pretend to hang ourselves for the cause. But no one present is excused. In the text, the character Magdalene, importantly, calls out France for its relationship to her country of Haiti. In the performance, in turn, de Mericourt calls out the (all white, like most of Poland) company—when, mid-frustrated monologue, she pointedly removes that actress’s unnecessary Afro-textured wig. As the play’s world devolved, it merged fully with the present. A back panel flew out to reveal an upstage filled with bold, black-and-white protest signs, painted with progressive slogans that would have fit in at any recent Women’s March.

From Stateswomen, Sluts Of The Revolution, Or The Learned Ladies (Żony stanu, dziwki rewolucji, a może i uczone białogłowy); text, dramaturgy, and costume design by Jolanta Janiczak; directed by Wiktor Rubin. Teatr Polski Bydgoszcz, 2016. Photo credit: Monika Stolarska

In the end, Roszczuk cried out: “Our theatre has been destroyed.” She meant it. This provocative piece—which won first prize at the Gdańsk R@port festival last year—had encountered enough resistance that this was its last performance. We understood, now, why a video screen showed the city square outside. Would there be a revolution now? Could there be? Those of us who took a sign and went—excitedly, dutifully, or otherwise—couldn’t a find a soul who cared, and the winter air suddenly felt very cold. Actors led us back through the building and delightfully, directly onto the stage.

The applause that filled the room was more than merited. It also felt precarious. In J.M. Barrie’s Peter Pan, the audience is tasked with Tinkerbell’s survival, asked to clap if we believe in fairies. It’s the theatre’s context, its contract—the suspension of disbelief—that can make it feel, for a moment, that we do. That we have the power. Janiczak gives the line to de Merincourt: “[Theatre is] a desperate attempt to restart the imagination. Are there any ideas backstage that we could maybe move outside these walls?”

From Stateswomen, Sluts Of The Revolution, Or The Learned Ladies (Żony stanu, dziwki rewolucji, a może i uczone białogłowy); text, dramaturgy, and costume design by Jolanta Janiczak; directed by Wiktor Rubin. Teatr Polski Bydgoszcz, 2016. Photo credit: Monika Stolarska

A special report on Divine Comedy Festival was prepared with support of the Adam Mickiewicz Institute – the national institution of the culture of Poland. To learn more about polish theatre go to http://culture.pl/en/category/performance

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Lauren Dubowski.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.