The tragedy of Shakespeare’s Desdemona haunts the literary canon. Her murder at the hands of her husband Othello, blinded by jealous rage, is no less troubling now than it was in 1603.

In Othello, Desdemona is an idealized woman, as director Peter Sellars notes – “a vision of perfection” – who remains mostly silent. In Desdemona, a collaboration between Nobel laureate Toni Morrison, singer-songwriter Rokia Traoré, and Sellars – currently showing in Melbourne – the voices of women take center stage.

The stage itself is a sparse graveyard, where Desdemona (Tina Benko) gets to give her side of the story from the afterlife.

Yet her tragedy has often taken a back seat to the difficulty of race in the play. Debate continues about how best to cast Othello — originally played in black-face — in light of the racism of the script and the complex identity that Othello constructs for himself as “assimilated other”.

In the opening scenes, Benko channels a caged restlessness. Her eyes dart around the theatre, her head moves in twitches — she is ill at ease. But her gaze is also defiant, as is her voice. She refuses the role of innocent, tragic bystander and the fate she was born into as a woman. She takes ownership of her life, and the choices she has made.

In what becomes the structure of the performance, we move between Morrison’s text and Traoré’s music. The calm and assured presence of Traoré and the four musicians accompanying her is a world apart from Benko’s Desdemona.

The compositions, incorporating voices, guitar, n’goni, and kora are beautiful, and Traoré’s voice compelling with its delicate strength and clarity. Most songs are sung in her native Bambara, spoken in Mali, West Africa, with the lyrics translated and projected.

I couldn’t help feel that absorbing them as text didn’t capture their quality in song, and this is perhaps telling of the difficulty of speaking across cultures and languages.

Yet it also drew attention to the two distinct writers at work. Morrison’s language was powerful and direct, speaking within the story, while Traoré’s more poetic lyrics sought to expand the themes of love, jealousy, and pride.

In terms of the onerous task of responding to the Bard, it was fitting that each found their own unique language, and Seller’s direction ensured neither voice dominated.

In preparing for this review, I became particularly conscious of my own preconceptions and how they might shape my critical response to the work. The gendered politics of critique have been hotly debated in recent weeks thanks to Jane Griffiths’ article examining reviews of her production of Antigone.

In the piece, Griffiths analyses such 10 reviews, highlighting the breakdown in response along gender lines. She writes:

The extraordinary division in gender in the critical response prompts me to analyse the assumptions, misinformation, and downright sexism out there in the critical cultural conversation.

Favorable reviews of her work, she writes, were written by female critics; the less favorable were by men.

Men who didn’t like the fact I didn’t write the story they wanted to see, or act the way they thought a woman should be. (Men) who would not engage with the world I was “narrativizing”. In other words, written by male critics who cannot or will not make the act of translation most women have spent their lives perfecting.

I am both white and male. I highlight this, and Griffith’s analysis, because this performance speaks to the subjectivity of both gender and race. From the outset, Desdemona speaks of the various ways that men make the rules.

She describes her lessons in constraint and duty, to lower her eyes as a subservient woman. Her only respite from the stultifying patriarchy was her African maid, who she knew as Barbary (a character fleshed out from the heartbroken Barbara). We hear how Desdemona cherished her, learned her songs, and the high standards for love she instilled.

As the performance progresses, Desdemona converses with the others who have joined her in the afterlife — Othello and Emilia. All speak through Desdemona and are voiced by Benko. While her Othello was initially confusing, hearing his story from her mouth built considerable psychological complexity.

Morrison’s Othello is immeasurably monstrous, and the secret brotherhood shared with Iago is painted here as the reason Othello succumbs to Iago’s deceit.

But this monstrosity highlights the strength of Desdemona’s love, which she gives not in spite of his wrongs, but in addition. Emilia pitched wonderfully by Benko, is caustic and forthright, challenging Desdemona to consider her own privilege. It shows the development of a more complex Desdemona, growing to perceive the limits of her own understanding.

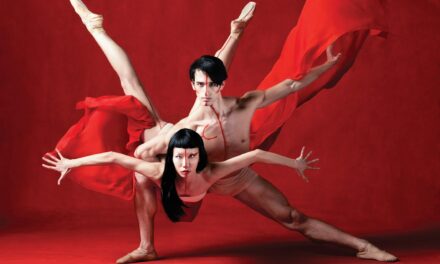

Desdemona. Mark Allan/Melbourne Festival

Nowhere is this more clear than in the scene where she finally speaks to Barbary. When Traoré voices the character, she steps between the two texts, speaking across them.

Tellingly, it is the first voice in Morrison’s script that does not emanate from the white actor on stage. When Desdemona says “You were my best friend” the response is unflinching:

I was your slave.

The brutal truth is not to apportion blame, but to clarify. And it is from this clarity that they begin to find a common ground. In an otherwise very still performance, they come together and embrace. There are no easy answers, though.

The characters all have their regrets, and therein lies the beauty of this production: to let them all speak. It is a timely reminder that many voices remain unheard.

This article originally appeared on The Conversation on October 19, 2015, and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Asher Warren.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.