What is opera? This is a question that has engaged puzzled commentators and practitioners since the well-documented origins of the art form in the late 16th century. The name itself is little help – the Italian word might best be translated as “work” – and many other terms have been used to define particular periods and manifestations of lyric theatre. Wagner spoke of influentially of “music drama,” but more recently there has been a growing fluidity between “traditional” opera and contemporary musical theatre, itself another rather amorphous area.

What’s in a name, anyway, and indeed, the creators of The Rabbits (a co-production between the Barking Gecko Theatre Company and Opera Australia) have a relaxed attitude to how the work might be categorised. Variously described by them as a musical, an opera, cabaret, and a song cycle, the work defies narrow classification and needs to be approached on its own terms.

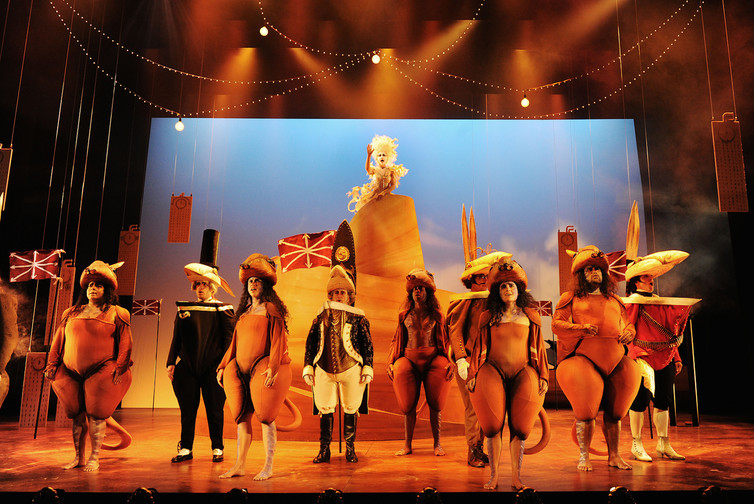

The Rabbits. Photo credit Jon Green

It is also unusual in that its source lies in an art book with very little text, rather than the more traditional plays, short stories, novels, or increasingly films, that constitute the bulk of contemporary opera librettos.

Based on the 1998 picture book The Rabbits, Shaun Tan’s evocative paintings from the book feed into the exquisite sets and costumes of the production, while John Marsden’s elliptical text has provided the basis for the expansion into Lally Katz’s libretto.

So does the music give us any clues as to a classification? The work opens with a solo passage for the central “character” of “The Bird,” which might be seen as a traditional coloratura soprano flourish overlaying a choral introduction.

There are many echoes of earlier operatic works: Mozart’s The Magic Flute immediately and most strongly springs to mind. Some of the vocal writing has baroque elements, accompanied by typically baroque orchestral features.

The Rabbits. Photo credit Jon Green

Early in the work, there is a waltz song which is pure Gilbert and Sullivan overlaid with a touch of French chanson, while other numbers range widely in stylistic influence from opera, operetta to a music hall. The work has discrete songs – many of them ensembles for the whole company or groupings thereof – which suggest a musical theatre aesthetic, but there is virtually no dialogue, unlike Mozart’s opera.

In many ways, the vocal aspects of the work blur the boundaries between genres. Mozart’s opera has a variety of dramatic influences but he writes for operatically trained singers – formidably trained singers in the case of the Queen of the Night.

In The Rabbits, there is a demarcation between the vocal demands for the two groups of characters: the marsupials – symbolic of the indigenous inhabitants of the land – have vocal writing inclined towards music theatre and pop, and the rabbits – the settlers or invaders – call for more operatically trained voices.

But there are many overlaps between the two groupings. Literally, towering over all of them is Kate Miller-Heidke as The Bird, the narrator of the events – operatically trained, but better known as a pop diva.

The Rabbits. Photo credit Jon Green

As composer, she makes some fierce demands on herself, requiring elements of the florid music reminiscent of the Queen of the Night, as well as the lusty belting of pop. The other voices range from quasi-counter tenor to pop.

The reception of the work has been uniformly positive – even more than positive at its premiere series of performances in Perth – while the Melbourne Festival performances, opening this Friday, have long been sold out, and the Sydney Festival ones will no doubt do the same. Why? Obviously, there is the recognition factor, a “pre-awareness” of the source of the work; it is a very well-known and loved book.

The Rabbits. Photo credit Jon Green

It also has a mythical quality that has universal application – opera has always appropriated myth, while the allegory of the predatory rabbits consuming all in their path has a particular resonance for Australia.

Kate Miller Heidke has a popular support base and will attract people who might not ordinarily go to the theatre. But the score itself is most inventive – it might be seen as a mash-up of musical styles – and provides a range of music that will attract a wider range of potential audiences than most contemporary opera.

The Rabbits. Photo credit Jon Green

Great credit must go to the arranger and musical director, Iain Grandage – who enjoyed richly deserved success for his own opera, The Riders, in 2014. Incidentally, both works make inventive use of a variety of birdcalls.

The Rabbits is a triumph for the creative team and must point the way forward for new collaborative projects between some of the smaller, inventive, but cash-strapped music theatre groups, and the well-resourced companies such as Opera Australia.

The Rabbits is at Melbourne Festival from October 9 to 13, details here, and at Sydney Festival from January 14 to 24, details here.![]()

Michael Halliwell, Associate Professor of Vocal Studies and Opera, University of Sydney

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Michael Halliwell.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.