Old soldiers fade away. Old theatre directors disappear more quickly. And old female directors can feel like those cartoon characters rubbed out by a giant eraser while they are still very much active. In June this year one of Australia’s most innovative, courageous and entrepreneurial women directors, Jules Wright, died of breast cancer. And the chances are, you’ve never heard of her.

Born in Melbourne and raised in Adelaide, Wright was one of our own. You can read her UK obituaries in the The Times, The Guardian, The Independent, and The Evening Standard–a wide cross-section of political opinion and cultural tastes. You can’t read her Australian obituaries anywhere, because there aren’t any.

Wright was an outspoken feminist and this marked all her theatre work. Having directed at school and later at Adelaide University, she migrated to the UK with her architect husband, Josh, in 1973.

There she began a Ph.D. in educational psychology at Bristol University. But soon she was directing at the Theatre Royal, Stratford East, then under Clare Venables, successor to the legendary working-class visionary Joan Littlewood.

Wright went on to become the first resident woman director at the Royal Court Theatre, and only the second woman to direct for its main stage. Her productions were marked by strong visual panache and a punchy disregard for convention. Among many other plays, she directed the premiere of Sarah Daniels’ excoriating denunciation of pornography, Masterpieces.

Between 1984 and 1987 she was an artistic director at the Liverpool Playhouse, whose financial fortunes she helped turn around. But perhaps most important of all, she was a co-founder of the Women’s Playhouse Trust (WPT), along with theatre luminaries such as Diana Quick, Diana Rigg, and Glenda Jackson.

In 1984 Wright directed the WPT’s opening production: Aphra Behn’s 1686 play The Lucky Chance, with a cast that included Harriet Walter, Alan Rickman, and Pam Ferris.

But this list of achievements doesn’t say anything about the kind of director Wright was. She was political, provocative, and passionate. Unfortunately, she seldom worked in Australia.

Exceptions were her pitch-perfect and beautifully balanced production of Caryl Churchill’s Ice Cream in 1990, and her uncompromising take on Thomas Middleton’s The Revenger’s Tragedy in 1991, both for the Sydney Theatre Company (STC). These were standout pieces of theatre.

The Revenger’s Tragedy in particular ruffled feathers. The reviews were snarky and some patrons made a point of flouncing out (not helped by the fact the STC insisted on handing out a crib sheet semaphoring audiences were in for A DIFFICULT PLAY.)

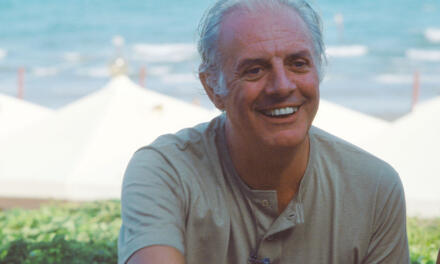

Jules Wright. Thomas Zanon-Larcher

Wright’s analysis of the sexism articulated in The Revenger’s Tragedy was both unflinching and intelligent. Set in a snowscaped Sicily in 1935, the production loitered in a graveyard, while glamorous Mafiosi planned tit-for-tat revenge among the monuments and malnourished trees.

As the men spouted misogyny and killed each other, the women figured out how to survive. At the end of the play, the women pulled a gauze curtain across the stage, concealing the ungainly pile of dead men. This telling final sequence underscored the point that, in a world full of macho madness, while women might be abused, assaulted, and demonized, they nevertheless manage to endure.

Wright’s research in psychology included looking at people, performance, and place. She was fascinated by how behavior, gesture, and setting relate to each other and used drama when she worked as a psychotherapist in the 1970s.

But she resisted the idea of a Stanislavskian method-based approach and insisted that people – and characters – were unpredictable and could act in radically discontinuous ways.

This made her a superb Second Wave feminist director, up for the challenge of both contemporary and classic texts. In the words of The Independent she viewed plays:

With today’s eyes and not yesterday’s prejudices.

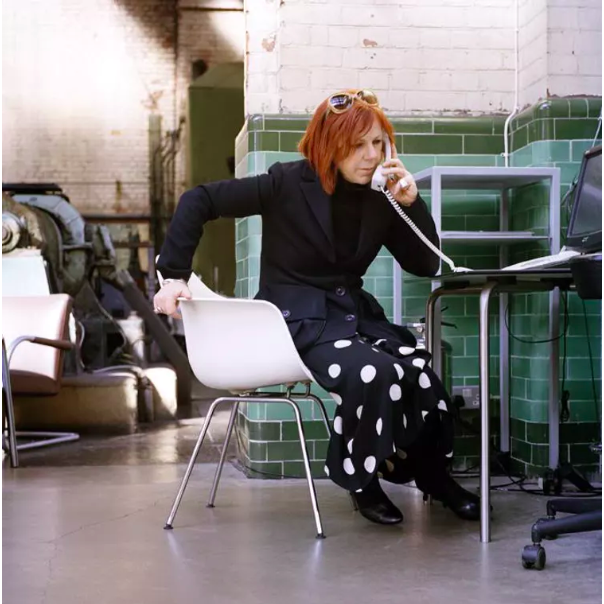

In 1993, Wright’s career took another turn when she moved from feted theatre director to becoming what we now call a creative entrepreneur. The Wapping Power Station was a disused crumbling concrete heap when she first saw it.

Together with her husband, she converted it into one of London’s most adventurous contemporary art galleries and eateries.

Wright raised £4m for the freehold and refurbishment and, after its official opening in 2000, it became a hothouse for new British art, and a fun place to be, known not only for its food and gothic surroundings but for its legendary parties and dress-ups.

For 20 years Wright made this Grade II-listed, industrial carcass a center for art, imagination, and discovery. Always impatient with bureaucracy, she never applied for a penny in government funding. In true patron style, the culture was paid for by profits from the restaurant.

Among the industrial metal fittings and echoing brick chambers, she worked with film-makers, composers, writers, visual artists, dancers and fashion designers.

The UK papers have been lavish in their praise of Wright, though she is hard to pigeon-hole as her achievements are so numerous and various. There is much to celebrate in the life of this quintessentially Australian theatre director, feminist and fighter for the arts.

We are left wondering whether an Australian sportsperson or politician half so accomplished would be so completely overlooked by the Australian media when they died.

This article originally appeared on The Conversation on October 21, 2015, and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Julian Meyrick and Elizabeth Schafer.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.