Last night, The Experiment – of which I’m part – opened at the Melbourne Festival. The story of its creation began six years ago and was guided by a series of serendipitous introductions.

In simple terms, The Experiment is just that: a musical monodrama in which our ambition was to look at the very nature of experimentation itself, as well as examine the interplay of two key themes: memory and trauma. It is a musical composition with theatrical elements. Not a theatre work with music.

Here’s how it came about:

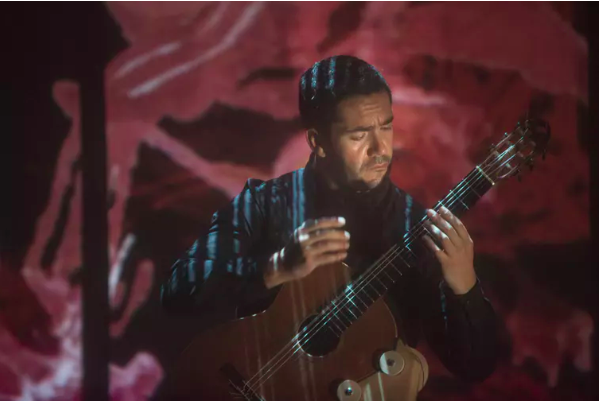

In 2009, I met Chilean guitarist Mauricio Carrasco in the south of France while I was in residence at Camargo Foundation in Cassis. Despite not having previously written for the guitar, I was struck by his skill and presence as a performer; we instantly agreed to make a work together.

It would feature music, of course, but also electronics, text, and video. This last element, we felt, was generally poorly conceived and executed within concert settings; we would do better.

A week later in London, I saw British playwright Mark Ravenhill perform the premiere of his 20-minute monologue The Experiment at Southwark Theatre. A darkly ingenious reflection on the ambiguity of memory, it was dense, punchy, and remarkable.

Ravenhill’s production told the story of Mengele-esque experiments on twin children that may or may not have happened. At its center was an unreliable narrator who may have been the perpetrator or the victim of these experiments. Or simply have seen them in a horror film or documentary. In his text, with its rare tone, cadence and power, there was rich material to work with.

And so we began work on translating Ravenhill’s monologue into a musical monodrama, a process that involved layering the text with music, light, sound, and video.

The provocation for Ravenhill’s text was Peter Singer’s Practical Ethics (1979), a contentious text that argues human supremacism lies at the heart of animal experimentation. Singer wrote:

If experimenters are not prepared to use orphaned humans with severe and irreversible brain damage, their readiness to use nonhuman animals seems to discriminate on the basis of species alone… There seems to be no morally relevant characteristic that such humans have which nonhuman animals lack.

The disquiet of this statement triggers primal responses in humans. The disquiet, the fundamental discomfort in knowing something to be true but nonetheless denying it, was an important point of reference as we developed the work and aestheticised Ravenhill’s script.

Our ambition was not to shock the audience – nothing so banal or naive – but rather to create a soporific meditation, in which questions are raised but not resolved, wherein the non-narrative ethical thought bubbles of Ravenhill’s and Singer’s ideas could menacingly float.

At its heart are the blinkered justifications of science at which Singer takes aim, and the collapse of classical witness-as-truth inquiry that Ravenhill is pre-occupied with. These inquiries work in parallel with a succession of reflections on the seductive, temporal and failed nature of gadget culture.

The work’s spoken word is delivered in muted underplayed tones – and by a musician, not an actor. Delivered in a sustained sotto voce, and offset with a dark filigree of muffled sound and musical interludes, this is composer, not director thinking.

The work brings together a team of collaborators, among them French painter and video artist Emmanuel Bernardoux, production designer Matthew Gingold, dramaturge Jude Anderson and production manager Lisa Osborn. Later in the piece we were joined by Argentinian guest composer Fernando Garnero, lighting designer Niklas Pajanti, sound consultants Byron Scullin and Marco Cher-Gibard, and artisanal makers Nara Demasson, Benjamin Kolaitis and Anna Conrick.

Our show is a technological wunderkammer in which the audience, seated under 48 speakers, are both the subject and observer of our experimentation. It works for some people. Others not so much. But it has been intriguing to watch this work splinter weird critical opinion in Sydney and Adelaide.

Fortunately, I like the weird. Not everyone can sit through John Water’s extraordinary camp/dark essay on hysteria Desperate Living (1977), or swallow in one sitting Alejandro Jodorowsky’s The Holy Mountain (1973). But like these two personal heroes, I prefer to work directly with the abstract immanence of symbols placed in relation to each other.

The myriad of readings that follow is for me far richer than more prescribed direct signposting.

The Experiment. Shane Reid.

What you will see and hear will in part be up to you. The Experiment is dark, dense, unrelenting, intentionally emotionally cold (like medical and scientific experimentation itself) and even bleak. But it is definitely not passive.

Like or hate it – or indeed in the case of some critics, both – The Experiment reminds me more and more of The Inquisitive Man (1814) by Russian fabulist Ivan Krylov, from which the English expression about the elephant in the room comes. There are many dark elephants in the room we have created.

It remains the task of audiences to decide what from within it they wish to remember, or indeed, perceive at all.

This post originally appeared on The Conversation on October 22, 2015, and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by David Chisholm.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.