How does an Artist wrestle with the truth of the past and win? To find out, Dramaturg, Producer, and Educator Cate Cammarata posed a few questions to Playwright Gary Morgenstein to shed some light on his new play, A Black and White Cookie.

Cate Cammarata: This story about racial, economic and political tensions set in today’s Lower East Side highlights many social problems being experienced by seniors today. What inspired you to write this play?

Gary Morgenstein: I set out to write a play about two seniors who will not go quietly into that good night. Harold Wilson, a gruff conservative African American, and Albie Sands, an eccentric Jewish Communist, are superficially very different, yet not, as both confront the fear of becoming irrelevant. They must surmount prejudice, in this instance anti-Semitism, to find their new friendship and their renewed faith in themselves and others. And then together they fight back against the establishment.

CC: Albie is a unique character straight out of a ‘60’s time machine. What was the most interesting aspect of creating this character who views our world from this vantage point?

GM: I found that while Albie did step out of a time machine, his views still resonate. I came of age in the late ’60s and early ’70s, marching against the Vietnam War, supporting civil rights for all. Though that tumultuous period was some 50 years ago, many of the issues remain like implacable viruses in the planet’s DNA. Albie’s humanism and desire to help others aren’t dated. Yet while Albie’s quite vocal in his views, Harold, the long-time Republican and Vietnam Vet, is just as opinionated and just as much a humanist in his own way.

CC: There is so much prejudice reflected in this piece on both sides, black and white. I was surprised to see the prejudice also reflected in Harold’s young, smart, black niece as well. So, you’re saying the prejudice is ubiquitous?

GM: My play focuses on anti-Semitism, that most ancient of bigotries, as a window into all prejudices. You’re very right that Carol Wilson’s smart – and a good person. It’s easy to write drama about good versus evil. Forgive the pun, but it’s oh so black and white. The preponderance of entertainment, especially ones that take on anti-Semitism, is about the Holocaust or white supremacists. Look at Hunters on Amazon and Plot Against America on HBO. Nazis are the villains. But it’s the decent prejudiced people who most worry me, not the extremists, because they’re the ones who look away and allow hate to flourish. The insidious nature of prejudice is that the bigoted person doesn’t think they’re bigoted. They hate Jews, say, because all Jews care about is money. To them, the prejudice is a function of fact. So to address that “fact,” we must take it head-on.

CC: Midpoint in your story, Albie and Harold join forces. Do you see this happening today, where once we get to know an individual the prejudice ceases? Increasingly we can’t explain why something happened without being accused of embracing that point of view.

GM: We can’t discuss unpleasant historical events or why you or I voted for that candidate without generating anger and accusations. A society which is afraid to think and respectfully consider different points of view will inevitably degrade its ability to understand. Then what? I walk a precarious line in A Black and White Cookie by daring to show where prejudice comes from without justifying it, while maintaining sympathy for the character overall.

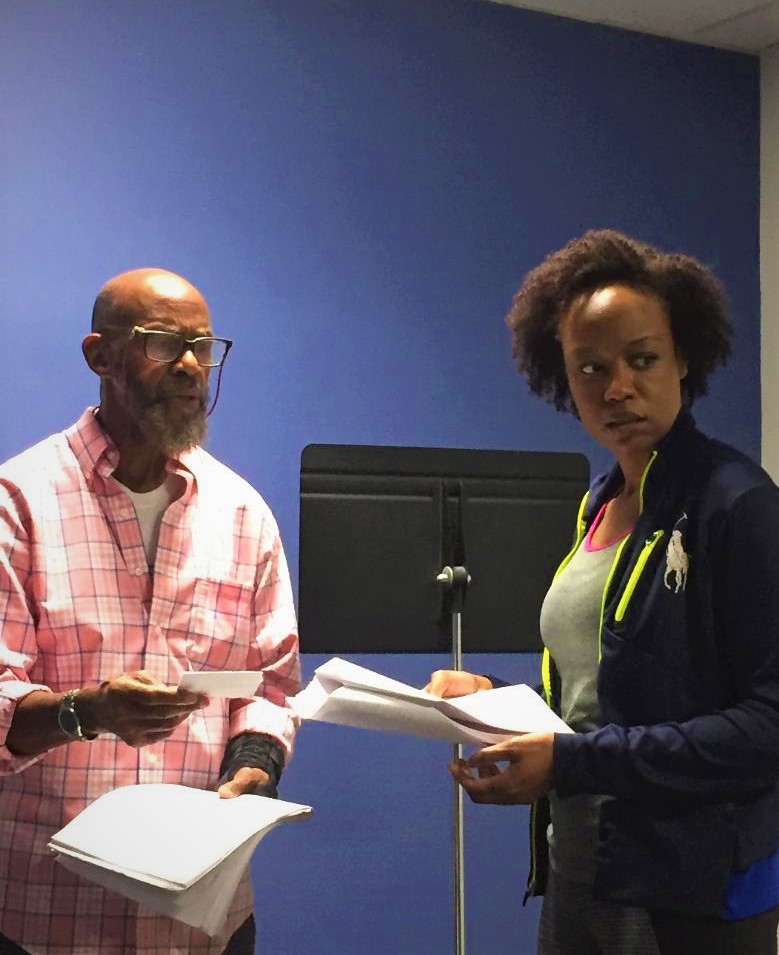

Mansoor Najee-ullah and Roslyn Seale.

CC: Both Albie and Harold were involved in the Vietnamese War, one as a protestor and one as a Marine. Do you still see that early experience still playing a part in today’s senior population?

GM: I think that the polarization induced by the Vietnam War still resonates among the general public in many other areas. We grew accustomed to demonizing those with whom we disagreed and it hasn’t stopped; it’s worsened thanks to Social Media. At some point, hope must trump polarization.

CC: You portray the economic hardship of our two senior characters. Is that also accurate, in your opinion?

GM: Since a senior is retired or semi-retired, their best earnings days behind them, living on a fixed income or susceptible to the vagaries of the stock market along with the price of health care, many seniors are simply more vulnerable, especially to feeling marginalized.

CC: Your play ends on a happy note, thanks to the generosity of an Asian banker. What message was it important for you to deliver through this rather deliberately happy ending?

GM: I’m a great believer in a positive message, no matter how provocative and rocky the journey might be. I hope the audience will think about how they think and, more so, how they view others to look past the divisive slogans and stereotypes to see each other as human beings.

CC: Like Akhtar Ahmed’s explosive play, Disgraced, you seem to set about building up every known prejudice to show ourselves to ourselves. Would you agree with this assessment? As a New Yorker, do you feel this is representative of our city today?

GM: Whenever my friends come to New York, I insist on taking them on the subway. No, not to torment them, but so they can experience the wondrous diversity of our City. Look around a typical subway car and see how everyone from all walks of life just sits there, oblivious to the differences of the passengers on either side, getting on with their day and the surly boss waiting for them. Yes, there is prejudice and there always will be, but there is also harmony and compatibility.

CC: What was your intention with this play? Why is this play important now?

GM: I wrote a humorous drama about regular folks. There are no speeches, no history lessons. No one’s a symbol. I wanted to show that at some point, we’ve all been “you people,” “those people.” Different. When you view someone that way, you delegitimize them; they’re not quite like the rest of us. If they’re not like the rest of us, they will slowly lose the rights to be treated the same. Once that door opens, physical, emotional, legal and spiritual assaults are tolerated because “you know how those people are.” Maybe they deserved it. Maybe they brought it on themselves. Until you wake up and realize that you’re now “one of those people” too.

CC: What are your production plans at the moment? I’d love to see this produced.

GM: And you’ll get that chance! A Black and White Cookie opens at the award-winning Theater for the New City on 155 First Avenue in Manhattan, running March 26-April 12.

I’m so proud to work with the wonderful director Joan Kane and the gifted cast of Jim Fromewick, Roslyn Seale, Chris Pisano-Collins, Julie T. Pham, and Mansoor Najee-ullah.

We’re also holding audience talk-backs following select performances to discuss the issues raised by the play. Our first one will be Sunday, March 29 after the 3PM show with acclaimed journalists Jack Rico of NBC News and Telemundo, who also created Viva Broadway, and Mike Sargent of WBAI Radio, who founded the Black Film Critics Circle.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Cate Cammarata.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.