An essay by Nora Amin that traces the presence of shadow theatre within the modern and contemporary Egyptian theatrical practices. From the analysis of the imaginative value of shadow, to the exploration of its aesthetic impact and its contribution to the contemporary notions of scenography and of liberating the Egyptian stage, Nora Amin presents a new examination of the connection that exists between the decolonization of the Egyptian stage, and the expansion of the theatrical discourse and form via the inspiration from the traditional sources of performativity.

Part Two (To read part one, published on The Theatre Times on November 7th, 2019, click here.)

If we move away from the historic perspective, and towards shadow theatre being a source of Egyptian and Arab drama and theatre – contrary to the allegations of coloniality, – we would be confronted by the aesthetic perspective. This perspective examines shadow play within modern and contemporary performative operations as a visual and aesthetic element. It impacts the creation of the performance’s identity, and what is called its ‘scenography.” From this perspective we can employ image analysis, and analysis of the shadow technique, in connection to the aesthetic identity of the performance. This leads us not to think of the usage of shadow in those performative experiences being merely an accessory or a reference to tradition, but rather as a vital artistic factor. This is profoundly related to the imagination of the artists creating the performance, and to their concept of visual imagery in connection to the dramatic and artistic identity of the performance.

From those exceptional experiences we see Bahaee Al-Mirghany, an Egyptian theatre director who died in the Suef Beni theatre fire on 5 September 2005. Bahaee is considered among the leaders of change in the Egyptian theatre. Towards the end of the 1980s, he launched his theatre group and directed several productions as part of the emerging Egyptian independent theatre movement. His intellectual discourse was highly critical and influenced by socialist ideology and philosophy. In his two most famous productions, The Road to the Mad House(Seket El-Saraya El-Safra) and An Evening with Shadow Theatre and Karakoz(Sahra maa’ khayak Eldel wel Aragoz), he introduced shadow theatre as a vital artistic and dramatic element separated from folkloric styling. His mature attempts put shadow play among the visual aesthetics and imagery of performance making, without any orientalist influences. On one hand, this introduction was new. It employed shadow within the dramatic performance and with a dramatic functionality, which liberated it from folklore and tradition. On the other hand, it opened the possibility of re-understanding the aesthetic potential of such sources as part of a revision and re-examination of performance in Egyptian culture.

Bahaee Al-Mirghany was joined by theatre luminary Hassan El-Geretly in the inauguration of a new definition of modernity in Egyptian theatre and performance. El-Geretly founded Al-Warsha Troupe in 1987 and has been its artistic director since its inception. Al-Warsha Troupe is recognised as the first independent theatre company in Egypt and has been seen as highly influential from the start.

Hassan El-Geretly is a profound well of theatre knowledge and reference. Our meeting with him on our research topic resulted in the inclusion of artistic and historic information covering the end of 1980s until present day. Besides this, El-Geretly possesses a unique analytical sense of the theatrical and performative phenomena in Egypt. His experience with shadow theatre employs a clear analysis of the role and functionality of this art within the modernist theatrical scene, and within the development of the general aesthetic vision that connects the image with physical and verbal expressions. Hassan El-Geretly’s artistic experiences include a powerful sense of an organic theatrical unity. The artistic elements do not appear as accessories or as mere operational elements. He does not create collages, but rather a performance that is based in unity of its elements and vision, a vision where no element can be eliminated or excluded. This means that Hassan visualizes his performance as a whole – he imagines it visually, verbally and physically. All the performative elements are composed as facets that complement each other within an organic unity and cannot be disconnected from each other.

In Dayer Dayer, Hassan El-Geretly presented the most important Egyptian experience of all, in relation to employing shadow theatre within modern performances. In 1990, El-Geretly, who had studied film and image in France, presented a theatre performance that put image as the main focus. This was a decision that was contrary to Egyptian theatre tradition that had previously been mostly reliant on verbal expression, without much attention given to the visual element. Before creating that performance, El-Geretly had worked as an assistant to the legendary Egyptian filmmaker Youssef Chahine, and followed this experience up by working with another prominent filmmaker, Youssry Nasrallah. Subsequently, the visual presence of El-Geretly’s creativity of was unmistakable, whether it was due to his study in France or to his work in filmmaking after returning to Egypt. As a consequence, one cannot understand his work – especially in the 1980s and 1990s – in performance without referring to the images and the aesthetics of the imagery central to his theatrical creations. He had come from the world of shadows and reflections.

A Stranger in Paper City. Arab Origami Center & El Gecko con botas, 2019.

If shadow play emerged from the earliest times spent around a campfire – and probably connected to later ritualistic practises that involved fire at night – which may have later connected to light in general, whether it was the elementary bulb or more developed electronic inventions. It leads us to think of a special paradox: that one needs light to create darkness. Light is necessary to create the dark figure that occupies darkness, which is called shadow. The light surrounding the shadowy, dark figure is not the centre of the spectator’s vision, it is rather the darkness that is shaped within, and by, the light. Similarly, one should consider the art of cinema is based on the same concepts of light and shadow. One should also contemplate the connections between shadow theatre and cinema as a medium that invested in developments of reflections and image capturing, and as an art of shadows that culminates in flat images projected on a screen – just as shadow plays use screens for their reflection/projection. While the techniques of making and projecting film differ from shadow theatre, cinema can still be seen as a visual, modernist development of the type of spectatorship that emerged with shadow theatre. In this sense, we can view the work of Hassan El-Geretly as a fusion between film and performance, at least aesthetically. We can also consider it a review of shadow theatre from a cinematic perspective, a perspective that links performance to image projection via shadow, the common factor between the two arts.

In 1985, at a shadow theatre performance in the Goethe Institute in Downtown Cairo, Hassan El-Geretly met Hassan Khanoufa and Ahmed El-Koumy. He had gone with Youssef Chahine to watch their performance that featured Hassan El-Faran’s screens and donkey-skin puppets. They were both preparing for Chahine’s movie The Sixth’s Day. Since that day, the memory of Khanoufa and El-Koumy playing together never left El-Geretly. It was a turning point for him. Both artists were icons of shadow theatre in Egypt. They had performed in the 1940s, but stopped for several reasons. Instead, they worked repairing old gas lamps. They lived on the roof top of an old building in Mohamed Aly Street, renown for being a hub for dancers and musicians, and only came back to shadow performance for the Goethe Institute performance. They had already forgotten several lines from the three stories that they had to deliver (Sudan War, The Monasteryand The Crocodile). Their private conversations behind the screen while moving the puppets became part of the performance. The spectators could clearly hear them while they tried to remind each other of the lines of the story. Those private conversations became a performance of their own, an unintended performance of two people who are the pioneers of shadow theatre and puppetry in Egypt, a performance of the living archive of their own memory of an art that was about to perish. It was a double performance: one of shadow theatre, and another of retrieving its personal archive – a brilliant moment in every sense.

Hassan El-Geretly considers Alfred Mikhail, who wrote “The Relation between Egyptian Cinema, Theatre and Shadow Play”, to be the most important scholar. Mikhail had conducted the research for his PhD in Paris (in French) under that title. When he returned to Egypt, he searched for Khanoufa and El-Koumy and brought them to present their performance at Goethe Institute in 1985. That night after the end of the performance and applause, Khanoufa and El-Koumy shouted at Youssef Chahine – who was among the audience – and said, “It was us who created the cinema!”

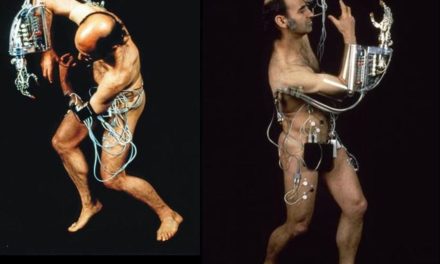

El-Geretly took the story of the crocodile and inserted it in his production Dayer Dayer. He brought Khanoufa and El-Koumy to perform it with shadow puppets. While he based Dayer Ma Ydoorand Dayer Dayeron the works of Alfred Jarry, El-Geretly did not consider the French plays of Alfred Jarry as sacred, nor did he consider Western theatre to be his model. Instead, he thought of Western theatre as sources and reference material that one can use as inspiration, while at the same time transforming them and developing them, and deconstructing the myth and hierarchy of knowledge that they perpetuate. He saw the past as a source, not as an idealist model, hence he regarded shadow theatre – and all traditional arts – as sources of inspiration. In this sense, El-Geretly could embrace those forms and transform them to suit his artistic vision and achieve an organic, aesthetic unity. This way he could also design the movement and dance in Dayer Dayeraccording to the visual logic and raison d’être of shadow, rather than according to the usual direct, forward-facing visual. He clearly articulated the arms, hands and head, but went beyond the small, detailed gestures that cannot be distinguished in shadow. He focused on bigger gestures and movements, and clearer limb articulation. Hence, El-Geretly moved from the common modes of manipulation in shadow play, to more creative and challenging choreography that respects the dynamics and perception of shadow. Instead of treating it as a traditional element, it was an aesthetic and dramatic element that is capable of inspiring and nourishing human movement and dance choreography. Therefore, it directly inspires and nourishes the performer’s work.

https://www.facebook.com/ELwarshaTheaterTroupe/videos/21622840762?s=686747366&v=e&sfns=mo

Along the same lines, El-Geretly designed the scenography of the performance from a shadow theatre perspective, which is the reason why shadow did not look alien from the overall performance aesthetics or lighting design. Shadow scenes appeared as an organic element that is part of the performance’s visual concept. Black and white had a powerful presence, a presence that was inspired from the necessities of shadow and its obligations. There were no colors in shadow, only black and white, light and darkness. There we could easily trace the visual extension of our black and white cinematic history. The shadow scenes appear in Dayer Dayeras a development of the cinematic image that has been part of Egyptian modern culture since the beginning of the twentieth century. Let’s not forget that Alexandria was the second city, after Paris, to ever screen a film. The shadow scene in El-Geretly’s performance also appeared as a symbolic and aesthetic tribute to the history and archive of Egyptian cinema. Shadow was undoubtedly a stubborn connection linking cinema and performance, reminding us of the presence of imagination, and proving the thesis of Alfred Mikhail.

The costume design in Dayer Dayershould also be analysed from the perspective of shadow aesthetics. Costume designer Nahed Nasrallah created an exceptional concept for her costume and jewelry design. Her design did not seem forced on the aesthetics of shadow, but seemed inspired from them. She respected the need to create costume lines and volume in order that the design appear in the shadow. Her costume designs were ideal for reflecting shape, size and power dynamics, even as shadows. She employed the aesthetics of Grotesque and exaggeration in the costume lines. Her concept supported the acting style and helped the actors to correctly characterize their roles. There was definitely a carnival-like mood. The relationships and dynamics between the characters were also supported by the costume design. The make up played a big role as well. The actors had their faces painted in black and white, as if wearing masks, and completed the shadow theme of masking faces and identities.

Additionally, the lighting design collaborated with the dynamic connection between reflected shadows and movement scenes, which were lit in a traditional, theatrical manner. Those two types of imagery – he shadow scenes, whether with puppetry or human bodies, and the theatrically light designed scenes – were absolutely balanced, and dramatically connected.

This relationship between shadow and mask reminds us of the shadow projection scenes in Egyptian theatre in the first half of the twentieth century. There was a traditional scene at that time that always involved shadow: a scene where a main character in the play revealed its true identity,by removing a symbolic mask and admitting its true persona. This dramatic function of the shadow proved its function as a medium to “hide”, as well as a medium to “reveal.” The symbolic meaning of “light,” in almost all languages, stands as synonymous to “truth.” And while the same linguistic symbolism of “shadow” is synonymous to “clandestineness,” the theatrical usage of “shadow” managed to reverse the meaning and symbolism by dramatically employing “shadow” in order to reveal the truth of the character. Nabil Bahgat points out that Naguib Al-Rihany – a leading actor and theatre director from the first half of the twentieth century – used this technique in his plays and cabaret performances. His then-spouse, Badiaa Masabni, a Lebanese dancer and leading figure of the Egyptian entertainment industry, also used shadow as an aesthetic, choreographic technique for her Baladidance (a form of Belly Dance and Oriental Dance) in her venue Casino Badiaa. The same technique appeared in relation to Baladidance scenes in several black and white Egyptian movies, as a form of stimulating the viewer’s attention by a potentially sensual scene. This cinematic technique brings us back to the shadow theatre of the human body, to Gaafar the Dancer, and establishes a clear bridge between the projected, dancing human figure from the fourth centuryandthe twentieth century. Let’s not forget that many Egyptian thriller movies in black and white also employed shadow scenes to show a murder being committed while masking the identity of the criminal.

Shadow stimulates human imagination. On one hand, it makes the spectator construct details by relying on his/her own imagination since the full truth cannot be exposed. On the other hand, it makes space for interpretation and for the construction of meaning by the spectator. Analytically, we believe this role and function of shadow can have a big impact on building alternative notions of spectatorship. Shadow can help reposition the spectator, and shift his/her role from a passive receiver, to a partner in creating and possessing meaning. Shadow opens a world of freedom, imagination and subjectivity when watching the performative act. It is a world able to provoke the spectator’s creativity and freedom, and guide him/her to play with the performance fairly and enjoyably. Shadow has the ability to unify spectators from diverse performance cultures and verbal languages during moments of imagination and ambiguity.

In present times, the Egyptian artists and theatre groups employing shadow theatre in performance include Mohamed Fawzy (Kayan Marionette). Fawzy founded what is known to be the first Egyptian movement and network for puppet theatre. He carried out a series of theatre productions where he focused on reinventing puppeteering in a way that fits contemporary topics. As an independent theatre artist, Fawzy directed three performances where shadow theatre played an important aesthetic role: Official Mission(Puppets’ Theatre, Ministry of Culture 2009) The Faraway(Studio Mansour Group, 2009), and Imaginations(Kayan Marionette, 2013). The first and last productions were aimed to children and young people, while The Farawaywas made for adults. What remains exceptional is that Fawzy not only presented shadow theatre within a production made for adults (The Faraway), but he created a whole production based on shadowtheatre in Dreams’ Hunting(Avant-Garde Theatre, Ministry of Culture, 2010). Compared to the occasional use of shadow and shadow puppets by other contemporary Egyptian theatre artists, Fawzy succeeded in composing a whole production based in the artistic identity and aesthetics of shadow theatre. As the title announces, Dreams’ Huntingemploys shadow theatre and shadow techniques to delve into a world of dreams. The dreams become identified with the shadow world. It is rare that it not only serves the imaginary world of the performance, but also reflects one meaning of shadow projection as being a dream.

If we move away from this model of a central use of shadow in contemporary Egyptian theatre – as best represented by Fawzy’s work – we will find numerous examples of minor and occasional use. These examples do not adopt the aesthetics of shadow theatre nor its imagery; instead it tries to inject one scene into the performance following common logic in theatre (i.e. crime scenes or sensual scenes). One also cannot ignore the phenomenon of using video projections and video beamers within theatre performance – the examples would be countless. Yet, the artists usually do not understand that this medium could be seen as an extension or development of shadow. They don’t recognise that it emerged from shadow, kaleidoscopic tools and other reflective tools and techniques. Technology has made it difficult for artists to use simple, non-electronic tools and strategies. Somehow, it restricts imagination and frames it as a one-way track – that of technology. The multimedia trend in contemporary Egyptian theatre has somewhat lost the connection to the roots of its imagination and imagery.

Nevertheless, from the point of view of Mohamed Al-Ekiaby, a prominent Egyptian shadow theatre artist and puppeteer and a member of the Arab Origami Centre, shadow theatre as a folk art is extremely important to Egyptian society. On one hand, he says it is an art that is capable of confronting the traditional fear conservative communities have of theatre and art. As part of traditional culture, shadow plays are acceptable and validating even within the most reactionary communities. As a technique that hides more than it reveals, it gently presents scenes that might be difficult for conservative spectators to handle, had it not been for the existence of shadow. Seeking refuge in the cultural heritage of the arts is a valid solution when artists face criticism and sensitive situations. On the other hand, he adds that shadow can be used as a dynamic tool that is able to create action in multiple locations within the performance area. Using shadow techniques is not a facile strategy; rather it is a tool that has to prove its necessity and place within the performance concept. Therefore, we return to El-Geretly’s view of the performative act as a whole; it is opposite to the ideological and politicised hierarchy of performing arts, and dramatic elements limited to their history and geographic locations.

While shadow puppets from the past made from donkey skin, Ekiaby fabricates his puppets from plastic. Nevertheless, he confirms that the material is dependent on the dramatic necessity and concept of the performance. In a performance where he worked with the theatre director Hany Al-Masry, Ekiaby created shadow puppets from donkey skin. Isis and Osiriswas a performance dealing with ancient Egyptian mythology; the theme therefore required traditional materials and techniques. Although the performance was never completed, Ekiaby describes its shadow technique and function as unique, as the shadow was used as a visual projection replacing the set and location. The shadow projections created the river and many other places; it also presented the surroundings and the physical elements the actors had to deal with. Shadow created a cinematic mood and environment in that performance.

Ekiaby also points out the possibility of fusing several puppetry techniques together. Contrary to the puppets that are traditionally operated by two strings and made of paper, we can make puppets that can be moved by several strings, providing a wider range of movement and manipulation for the puppeteer. This again leads us to contemplate modernist development of folk and traditional arts and their transformation into contemporary art forms, instead of remaining museum pieces.

For several years, the Arab Origami Centre worked towards the promotion and education of the art of origami. Although widely considered a Japanese art, origami – the art of folding paper – became a passion of Ossama Helmy, who introduced it in Egypt and made himself a leading figure of the art form in the Arab region. Ossama Helmy developed the use of origami and integrated it into performances of storytelling and puppetry. He mixed it with shadow theatre and marionettes in stories for children and for adults, and in production collaborations within the Arab countries as well as with Germany. In his work, origami plays a vital role of stimulating interaction between and with spectators. This creates a physical action that is participatory, creates equality between the stage and spectators, and creates equality among the spectators as well. His style cannot be called foreign nor Japanese, it can only be called personal. It is the result of inspiration, and of personal and subjective creativity and passion. In this way, an artist can create a dialogue between different art forms and performance cultures. He/she can transform them into something new, contemporary and authentic. In his new project, Unfolding Dialogue’s Light, he collaborates with Spanish artist Elena Diez Villagrasa (known by the pseudonym Clementina Kura-Kura) in order to re-examine the possibilities of making performances that are a representation of dialogue, and an experiment in fusing arts and knowledge. In their new experiment, Diez Villagrasa says that they will employ an overhead projector that is traditionally used in the classroom. They will attempt to use it to create shadow scenes, hopefully making new visual possibilities and new aesthetics out of this fusion and dialogue. The overhead projector would provide new imagery that is created horizontally instead of only vertically; it will allow the shadows to be more detailed and present different, expanded perspectives and perceptions.

Contrary to the popular opinion, we believe arts that are labeled as traditional can become vital sources of inspiration. They can be liberated from stagnation, and from being framed by the past. Those arts can become bridges and catalysts of dialogue and transformation. There is no better proof than the artists that we have approached, their artistic experiences that have created new aesthetics of performance, and opened new horizons in imagery, imagination and performance making. Above all, those experiences have succeeded in liberating spectatorship, and re-positioning the spectator from an active point of view. The continuation of research and examination of such endeavours will help to support unconventional experiences, and free them from the traditional, colonial gaze and ideology that defines what is modern/civilised/superior, versus what is “old.”

In shadow, revolution can be born. In darkness, bright ideas emerge. The direct light might be a power that obliges us to see what we are “supposed” to see, not what we want to imagine. Imagination is the twin of freedom and revolution.

This publication is produced by the support of the European Union. The content of this publication is the sole responsibility of the Arab Origami Center and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the European Union.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Nora Amin.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.